![]()

Chapter 1

Thinking Like Shakespeare

What a piece of work is a man, how noble in reason, how infinite in faculties, in form and moving, how express and admirable, in action, how like an angel, in apprehension, how like a god! the beauty of the world; the paragon of animals. . . .

(Hamlet, II, ii, 303–7)

Shakespeare was a quintessential holistic thinker. Nature had gifted him with an extraordinary aptitude to navigate fluidly between the realms of intellect and imagination. Through his dramatic writing, Shakespeare found the ideal vehicle for the exploration and refinement of his abundant talents. Even the playwright’s contemporaries marveled at his twin facility for deep intellectual engagement and creative expressiveness. In the memorial First Folio, fellow actor Richard Condell wrote, “[Shakespeare’s] hand and mind went together, and what he thought, he uttered with that easiness that we have scarce received from him a blot in his papers.” Of course, such effort comes harder for ordinary mortals. In the modern Shakespeare classroom, encouraging modes of thought more closely aligned with the playwright’s holistic mindset can optimize students’ mental flexibility, comprehension, and receptivity. By learning to think like Shakespeare, we can acquire a deeper appreciation and enjoyment of his plays.

Poised on the Corpus Callosum

Both Shakespeare’s cultural environment and his natural gifts contributed to his exceptional intellectual flexibility. Borrowing from the parlance of modern neuroscience, Shakespeare might be described as “intellectually ambidextrous.” Mental-sidedness or dexterity refers to a person’s natural inclination toward either right- or left-brain thinking. Of course, everyone is born with the potential to utilize both right- and left-brain functions. Everyday life demands constant transition and communication between cerebral regions in order to accomplish the myriad tasks that require our attention. Just as a dance teacher or an athletic coach can train students to fully utilize both sides of the body despite dominant physical sidedness, an intellectually open classroom setting can also cultivate mental ambidexterity in students. The holistic Shakespeare classroom both requires and encourages this open and intellectually flexible learner.

As children, uninhibited imaginative play, centered predominantly in right-brain modalities, is encouraged and rewarded. But when youngsters enter school, they quickly discover that most conventional instruction favors left-brain learners. Consequently, early learners make unconscious efforts to harness their uniqueness and individuality to fit within the narrow confines of the traditional classroom. Self-labeling and conformity are the inevitable results, producing vestigial learners who are inhibited from accessing their full intellectual capacity (Rubenzer 1982). Holistic teaching seeks to reunify this vestigial learner.

Brain functions are divided into two distinct but complementary hemispheres, each governing specific skills and ways of processing information (see Molfese and Segalowitz, 1988). Organically, the left side of the brain controls linear, analytical thinking, stores and processes facts and details, and develops problem-solving strategies. The left-brain also facilitates categorization and labeling and allows for comprehension of the past and present. Classroom activities that rely on left-brain functions promote precision, logic, and orderliness. In Shakespeare studies, students might engage this area of the brain through scansion and scoring exercises that foster recognition of language patterns, parts, and groupings, or by compiling data that compares everyday living conditions in Elizabethan England with those of the modern era. Most mathematicians and scientists incline naturally toward left-brain thinking. In contrast, many people with artistic temperaments gravitate toward right-brain activities and thought patterns. Right-brain-sidedness governs abstract thought, artistic ability, and spatial awareness. It allows appreciation of the whole, grasps interdependences between parts of instructional material, facilitates conceptual and abstract thinking, expresses states of being, and is future oriented. Right-brain learners tend to favor subjective and imaginative classroom activities and demonstrate a natural proclivity for interpretive exercises and theoretical content. Teachers of Shakespeare might develop right-brain learning by eliciting students’ personal readings of symbolism or imagery, or encourage proclivity for spatial awareness through hands-on exercises like set design, movement activities, or stage blocking. Visualization, music, dance, and other sensory-based media, rather than language, are powerful resources for tapping into the right-brained student’s potential for nonverbal learning.

The topic of brain hemispheric functions has sparked a wealth of provocative literature in the past decade, including Daniel Pink’s phenomenal bestseller, A Whole New Brain: Moving from the Information Age to the Conceptual Age (2005). Recent science has made significant advances in deciphering the correlation between language cognition and brain regions, and proven that brain hemispheric lateralization is not as fixed and compartmentalized as previously believed (see Sahin, Pinker, Cash, Schomer, and Halgren 2009). The human brain has been likened to a parallel processor because of its ability to simultaneously receive and process stimuli in opposing cerebral regions. Language studies have revealed, for example, that expressive vocalization, which includes inflection, intonation, pitch, stress, and rhythm (essential tools for effective communication and performance) is usually lateralized in the right brain, while literal language functions like grammar and vocabulary most often originate in the left brain (see Pinker 1994; Deacon 1997; Brown and Hagoort 2001). Some language functions, however, appear to be controlled bilaterally. Thus coherent and expressive verbal communication, like most other human activities, requires free access to both sides of the brain. Anatomically, the corpus callosum, a band of connective neural fibers, links left- and right-brain hemispheres. In the holistic Shakespeare classroom, students are encouraged to envision themselves as poised on that vital cerebral bridge, ready to travel along this open pathway between discrete ways of learning.

The Holistic Triad: Wholeness, Interconnectivity, and Embodiment

As discussed in the Introduction, holistic classroom Shakespeare embraces three core values: wholeness, interconnectivity, and embodiment. A cultural environment that placed value on systemic thought and cultivation of the WHOLE individual enhanced Shakespeare’s natural proclivity for holistic thought. Contrary to popular misconceptions, holistic ideology is not a New Age phenomenon; its roots stretch back to the classical era when great thinkers including Aristotle, Plato, and the physician-philosopher Galen contemplated the relationship between man and his environment, and developed an integrated, systemic worldview rooted in appreciation for the whole of human potential. In the Renaissance era, a resurgence of interest in the writings of the Greek and Roman philosophers reawakened the holistic viewpoint, which in turn became a key influence on humanist learning. By Shakespeare’s lifetime, holistic thought imbued every aspect of Elizabethan/Jacobean culture, from humanist education to philosophy to the sciences, providing one of the most profound influences on Shakespeare’s perceptions of the world in which he lived.

The golden age of Tudor civilization honored the polymath as the pinnacle of human excellence. In contrast to our modern society which values, and even demands, increasingly narrow (and early) concentrations in educational and career tracks, Elizabethan society recognized and encouraged man’s limitless potential for knowledge across a broad spectrum of disciplines and talents. In today’s climate of super-specialization, the quest for well-roundedness might seem antiquated and antithetical. But at the center of Tudor court life, Queen Elizabeth, a remarkably talented linguist, writer, musician, dancer, athlete, and stateswoman, served as the pivotal role model for her courtiers, who sought to emulate her astonishing array of diverse interests and accomplishments. Through her personal example and demanding standards, Queen Elizabeth set the stage for the extraordinarily rich artistic and intellectual climate that enlivened the English court during the latter half of the sixteenth century.

As both a man and artist, Shakespeare was one of his society’s most fully realized holistic products. Written in an era before access to dictionaries, glossaries, and Internet search engines, his plays reveal an exceptional command of vocabulary and a familiarity with an astonishing breadth of subjects, ranging from horticulture to seamanship to the law that can only be the product of wide reading and insatiable curiosity. His career accomplishments exemplify genuine integration of high artistry and high intellect. In his professional life, Shakespeare not only wrote plays, he acted in them, and may have had a hand in their direction. He was an astute businessman and investor, retiring as one of the wealthiest citizens of his native Stratford-upon-Avon. Ironically, early in his career, Shakespeare’s multifaceted talents even attracted the jealousy of rival playwright Robert Greene, who famously disparaged Shakespeare as a “Johannes factotum,” or Jack of all trades. (It is worth noting, however, that Greene’s slighting comments seem to arise primarily from educational elitism; he was a member of the so-called University Wits, a small group of university-educated dramatists, and was apparently stung by the public notice being paid to this less-educated newcomer from the country. Greene’s publisher later apologized for his comments.)

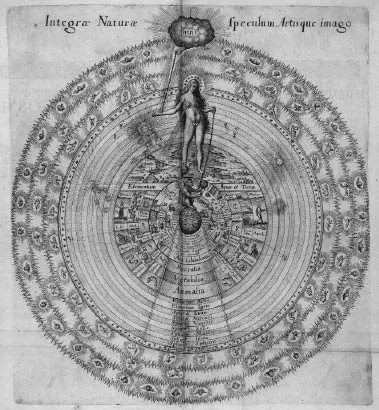

Alongside the ideal of personal wholeness that Shakespeare personified, universal INTERCONNECTIVITY was a central preoccupation of Renaissance thinkers. Writing in the mid-twentieth century, the scholars E. M. W. Tillyard and A. O. Lovejoy concluded that Renaissance society was ordered in the concept of a hierarchical universe with God as its divine architect. According to this theory, Shakespeare’s contemporaries found beauty, balance, and fitness in the logical orderliness of existence, which they attributed to the hand of God. They believed that discrete parts of the cosmos could only be fully understood by studying their relationship to other components of the universe, and by discovering affinities in dissimilarities. This penchant for exploring interlinkages was illustrated in the Great Chain of Being, which Lovejoy and Tillyard proposed as one of the most enduring cosmological metaphors of the medieval and Renaissance periods, exerting an inestimable influence on literature, visual art, politics, metaphysics, and philosophy. (By the late-twentieth century, with the advent of new historicism, gender studies, Marxist criticism, and a host of other scholarly perspectives, many scholars dismissed Tillyard and Lovejoy’s conclusions as overly simplistic. Nevertheless, despite charges of datedness, they remain a crucial foundational component of the history of ideas, and an invaluable adjunct to the examination of status, alliance, and identity during the period.)

The concept of the Great Chain of Being arose from the premise that all living creatures and inanimate objects occupied a preordained hierarchical position on a natural ladder. At the top of the ladder was God. Descending vertically, angels inhabited the rungs closest to God, since they possessed the highest concentration of spirit. At the bottom of the ladder, rocks and other inanimate objects had their assigned places, since they lacked feelings, soul, or intellect. Plants, living but insensate, were positioned just above nonliving objects, followed by animals, which were more closely aligned with the region of matter than spirit. Man occupied a unique position in the middle of the ladder, balanced between the realms of pure animal and pure spirit. Capable of reason and the ability to impose order on his environment through the use of language, man possessed a soul that set him above and apart from other animals, yet he remained connected to his animal impulses through his physical appetites and senses.

Any disruption in the calm stability of the Great Chain of Being reverberated all along its length. A weakened link near the top of the chain imperiled all the rungs below; since any agitation could have disastrous consequences for the totality of the chain, each rung was both dependent on those above and responsible for those below. In Troilus and Cressida, Shakespeare references the natural ladder as a cosmic stabilizer, a finely tuned string upon which cosmic harmony depends:

Depiction of the Great Chain of Being from Robert Fludd’s 1617 Utriusque cosmic-historia. By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

The heavens themselves, the planets, and this centre

Observe degree, priority, and place. . . .

. . . But when the planets

In evil mixture to disorder wander,

What plagues and what portents, what mutiny!

. . . O, when degree is shak’d,

Which is the ladder of all high designs,

Then enterprise is sick. How could communities,

Degrees in schools, and brotherhoods in cities,

Peaceful commerce from dividable shores,

The primogenitive and due of birth,

Prerogative of age, crowns, sceptres, laurels,

But by degree stand in authentic place?

Take but degree away, untune that string,

And, hark, what discord follows!

(Troilus and Cressida, I, iii, 85–6, 94–6, 101–10)

While the Great Chain of Being reinforced Renaissance ideas about the fixedness of social status (a notion appropriately abandoned in modern civilization), it also served as an influential cultural metaphor that advanced awareness of continuity and communal responsibility, two foundational tenets of modern holistic thought. Every member of Elizabethan society was aware of both his/her dependence on and responsibilities to other people. Today, the chain provides an insightful resource for enlightening modern students about the power structures that underscore every Shakespearean play, provoking conversation and consideration of relationships and social dynamics and expressing the values of community and connectedness embedded in the holistic mentality.

Analogical thinking comprised the dominant cognitive mode of the Renaissance period. Using the analogical method, learners gain insights by comparing new information with familiar concepts through the recognition of patterns and similarities. In contrast, current educational models tend to emphasize atomistic or mechanistic thinking that divides subject matter into parts, often with little reference to the whole. One familiar example of analogical cognition is exemplified by the Renaissance doctrine of correspondences, which contended that just as God governed the angels, the king was head and ruler of men, and the lion the king of beasts (Tillyard 1961). This penchant for discovering analogies or correspondences was a definitive element of Renaissance thought and remains one of the most powerful instructional tools for the holistic Shakespeare teacher.

A significant example of correspondence is illustrated by contemporary perceptions of the human body, which was regarded as a “small world,” or microcosm, a miniature replication of the “great universe,” or macrocosm (Tillyard 1961). Perfect and beautiful in its composition, the human body mirrored in its structure, organs, and natural processes a variety of corollary cycles and systems, ranging from the passage of the seasons to the movement of the planets. Belief in embodied emotion, a further outgrowth of the concept of correspondence, comprised another of the seminal axioms of Renaissance medicine and anatomy. Based on Greek medical theory, the principle of emotional EMBODIMENT was rooted in the presumption that human passions are both situational and organic; that is, they may be provoked either by traumatic life events or by constitutional imbalances caused by humors, bodily fluids produced by the liver, spleen, lungs, and gall bladder (Paster 2004). When the humors were in appropriate balance, medical practitioners believed, a patient’s temperament and mood were moderate and controlled. However, during times of illness or stress, excessive production of one or more of the humors caused noxious gases to travel to the patient’s brain, causing emotional disturbances that required medical intervention, such as blood-letting or the administration of purgatives. Disruption of the unity and harmonious functioning of the body might also be triggered by societal or cosmic unrest and vice versa. In King Lear, for example, the aging king’s mental deterioration is paralleled by unusual climatic events, such as storms and eclipses. Thus, Shakespeare’s plays provide a rich mine for renewing awareness and contemplation of the symbiotic relationship between body, mind, spirit, and environment.

1574 engraving depicting the humours. The Four Humours, from ‘Quinta Essentia’ by Leonhart Thurneisser zun Thurn (1531–95/6) published in Leipzig, 1574 (engraving) (b/w photo) by German School, (sixteenth century) Private Collection/ Archives Charmet/ The Bridgeman Art Library.

Shakespeare’s Education

Although no records have survived that document Shakespeare’s school enrollment, as the son of a local official, Shakespeare was entitled to free education at his local grammar school. By Shakespeare’s schooldays the Tudor educational system had undergone reforms aimed at establishing a standard curriculum to ensure that all Protestants could read the Bible. Roger Ashcam, the highly regarded tutor of Elizabeth I, detailed a new, progressive instructional model in his book The Scholemaster, in which he extolled gentle correction and a collaborative relationship between student and instructor. Praise, mutual respect, and interactivity were keynotes of Ascham’s teaching model, with focus placed on the instructor’s role as facilitator and encourager of student learning: “This is a lively and perfect way of teaching of [linguistic] rules; where the common way, used in common schools, to read the grammar alone by itself, is tedious for the master, hard for the scholar, cold and uncomfortable for them both” (quoted in McDonald 2001, p. 66).

Although many negative elements of the Tudor educational model, such as the widespread practices of caning and other forms of corporal discipline, insistence on rote repetition and memorization, and the demand for unquestioning obedience to the schoolmaster are at stark odds with the aims of holistic education, a couple of beneficial attributes of Tudor schooling are worth noting as possible influences on Shakespeare’s receptive imagination.

Content Immersion

At the King’s New School, the Stratford-upon-Avon grammar school that Shakespeare likely attended throughout his...