- 162 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Flesh Into Light by Robert A. Haller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Beginnings

In 1970 Amy Greenfield began to make motion pictures that were based on the unexplored potential of filmed images of the body in movement. She was convinced that dance on film as film had only rarely been made. As a dancer-choreographer in the 1960s, she had been recorded – filmed – in several projects, but knew that those films had none of the penetrating energy and ideas of her favorite film-makers – Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, Jean Cocteau, Michael Powell, Stan Brakhage, Jonas Mekas, Gregory Markopoulos, and Kenneth Anger.

In 1995 (in an article for Film Comment) Greenfield recalled the lasting impact of seeing Michael Powell’s two films that are set in worlds inhabited by dancers:

The only time my mother took me to the movies as a small child was to see a double bill, The Red Shoes and The Tales of Hoffmann. Afterward I wanted to see The Red Shoes over and over, and so I also saw The Tales of Hoffmann repeatedly. All that stayed with me of the latter film was a feeling of chaos, darkness, mystery, in an unreal world I wished was real.

In six pages she analyzes The Tales of Hoffman at length. As she discusses the actress Pamela Brown’s performance, Greenfield speaks of both her own (Greenfield’s) and Powell’s vision – revealing the aesthetic posture they share.

In his memoirs Powell described the discovery that the male character Nicklaus – played by Pamela Brown – is actually a woman, and that her final appearance, with breasts bared and body painted gold, would be “an apotheosis.” Greenfield writes that this transformative moment was

the revelation of Brown’s body as art, a sensual yet otherworldly revelation of the power of art to transcend loss and death.

This declaration of the potential of the body as art (this sequence was precious to Powell but finally was not included in the finished film) can be applied to nearly every film made by Greenfield. Bodies – made into art through the selective medium of film – speak across time and to people across space and cultures. By filming movements that are known to and experienced by all of us Greenfield opens, in these acts of the body, windows on the ideas and emotions within us.

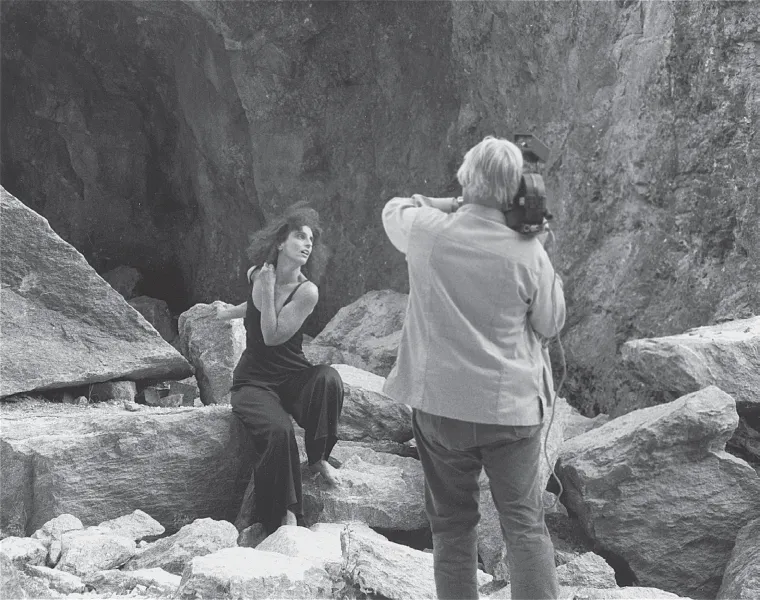

Hilary Harris filming Amy Greenfield on the location of Antigone/Rites of Passion (1985).

This archetypal imagery from the realm of spontaneous movement and informal gestures belongs to all of us. And they are distilled by the close-up, a basic tool for Greenfield, as is the compression of time (neither possible in the theatrical dance world). Overlooked movements, everyday moments, appear in her films. T. S. Eliot, in his “Four Quartets,” writes of something similar: “Not known because not looked for.”

Cinema’s affinity for movement had been rapidly recognized by early film-makers. But the frontier of expression, where the photographed images of cinema met with the physicality of dance, was almost never crossed by early choreographers or film directors.

Moving bodies, moving pictures

Ultimately, the most affecting dance is sensual, and about interior states. So is cinema. At this frontier Greenfield found her way with the camera into the world through the body. The director Robert Bresson, in words she did not know of until 2003, said something similar in 1965: that the film-maker should “get as close as possible, to penetrate things.”

To “get close” is something that we see in her first film, Encounter, and also in her later films. Greenfield wrote about this in a program note for her 1980 videotape 4 Solos for 4 Women. She wrote that

the daring of the dance for the camera is not in the daring of the leap. It is the complex close-up revelation of a human being. Our space in 4 Solos was the space of the lens, the drama of our relation to the camera.

For Greenfield the body, moving with, and against, the close-up camera, can be the concrete image of inner human nature, an instrument for its expression, and a vessel containing images and actions that crystalize the meaning and mysteries of experience: memory and movement, the past and the present moment.

Movement by the camera, movement of focus by the lens, movement by the performers before the lens, and external movement in the environment where her films are set – the visible effect of the wind, the swirl of water – all energize her films. Last is movement constructed on the editing table, where Greenfield organizes images (often rapidly) in ways that are kinetic, surprising, freighted with emotion.

An example: in Tides – and in other later films – she reverses the flow of time (and the movement of the ocean), but gives the spectator no immediate notice of this, leaving to the viewer both discovery and an enhanced visual experience.

At their conclusion her films impart a sense of ecstatic fulfillment – or death (but not defeat) – as they take us, with her protagonists, to or beyond physical limits.

From the beginning she has worked with film-makers who were concerned with what is cinematic and adventurous. Specifically Hilary Harris (1930–99), a pioneer of cinematic form in the 1960s, was a mentor and cameraman for Greenfield in the 1970s and 1980s. Richard Leacock (1921–2011), one of the founders of “cinema verite,” was also a mentor and cameraman for Greenfield in the 1970s and the 1980s. They were drawn to her projects by what Harris once told this writer were her “unorthodox” methods and images – and the freewheeling cinematic kinesthesia they allowed – things Harris and Leacock had both valued since the 1950s. Leacock said that doing camerawork for Greenfield brought back the joy he had experienced when he first used a movie camera.

Encounter (1970). Color, silent, 8 minutes

An explosion of sheer dynamic movement, Encounter is a vortex of struggling, desperate bodies.

This is the first film Greenfield directed and the first film she chose to place in distribution. It was not the first time she had appeared on film, but those earlier works were not formed by her, nor did they emerge from within her. Encounter is not the film of a performer but a director. In Encounter Greenfield engages with many of the themes and strategies that characterize her films over the next 3 decades.

Greenfield was a writer and poet before she became a film-maker. In 1968 she wrote an article that was published in the January 1969 issue of Filmmakers’ Newsletter. In “Dance As Film” she proposed to “take a step forward in developing dance into filmic dance” and agreed with Stan Brakhage “that a dance film in the sense of a dancer sensing movement as film hasn’t been made.” What was needed, she said, was that the dancer, his/herself, be aware of “the energy of human body motion interacting with camera motion … [and] the principles of non-chronological (non-physical) time in editing.”

As a declaration of intent – after she had performed in films photographed and edited by others, and before she had directed her first film, Encounter – these propositions are remarkable in so precisely describing her artistic agenda for at least the next 15 years.

Densely edited, rapidly flowing, Encounter is a challenge to describe. Here I will present a shot list of the first 45 seconds of the film to give a sense of the nature of this debut motion picture. It was filmed on Super 8mm – which helps to explain the very mobile camera. The film then was enlarged to 16mm (but it does not look like an enlargement).

1.title shot – “encounter”

2.title shot – “by amy greenfield”

3.image of a young woman in a paisley skirt, sitting on a stone bench; a slow zoom toward her; she sits with her head bowed, her face not visible.

4.title shot – “camera michel goldman”

5.title shot – “danced by amy greenfield and rima wolff”

6.black footage for a few seconds [at this point the shots discussed in the text begin]

7.a woman in a paisley dress is twisted/guided to screen right by a second woman in a paisley dress; this 16 second shot flows uninterrupted with the camera rising above and 9 following the turning figures who appear to be struggling.

8.a very tight close-up shot of paisley body fragments continuing the movements of shot # 7.

9.a stationary, 1-second shot of a paisley-dressed woman crouched at screen left, with a cryptic white rectangle in the center of the frame.

10.another shot, from a different angle, of short duration, of the movements in shot # 7.

11.a repeat of the nearly abstract action of shot # 8.

12.a paisley-dressed woman, with head bowed forward, at screen left.

13.a brief shot of the turning action of shot # 7

14.a shot of the feet of the turning woman.

15.a different abstract close-up, like shot # 8

16.a repeat of the movement in shot # 7, but very brief.

17.the limp figure of a paisley woman, her head obscured, with the camera circling to the right (it is ambiguous when watching this quick shot if the woman is cradled in the arms of the second).

18.a very fast, brief shot of the turning movement.

19.a half-second repeat of the movement in shot # 7.

20.a close-up of a paisley-dressed woman on the bench at screen right, seen from the waist down.

21.a quarter-second shot of a spinning paisley-dressed body.

22.a 2-second, somewhat abstract shot, of bands of paisley material, stretched horizontally across the film frame.

23.an overhead shot of a paisley-dressed woman on the stone bench, or lying on the floor with her legs propped up against the wall.

How does one read this 45-second stream of images? To begin, there is no conventional narrative. We are told in the credits that the film is “danced by” two women. But distinguishing between the two is all but impossible because of costume and camera angles. Their movements are all fragments of the turning movement in shot # 7, or stationary shots like # 9, where one can suspect that one of the two women is imagining or remembering all of the movement shots.

But if the dramatic meaning is ambiguous, the physical act(s) of the 45 seconds are precise. The two women turn to the right and the camera follows them, then rises above them. All three glide in separate, linked arcs.

The women turn/struggle/remember (?) again and again, very often in shots with a duration as brief as one-sixth of a second. Greenfield thrusts them across two kinds of space with great speed, whether it is some kind of daylit plaza, or a black void. These two kinds of space may imply two sets of perceptions, perhaps from each woman. Or two perceptions from one? The velocity of editing provokes such questions and restrains us from arriving at any definite answers.

As the film continues, the movements of the two women change. Instead of being centripetal (turning inward upon themselves), the two briefly appear to merge, and then separate, moving away from each other into different spaces. Rima Wolff (who can now be distinguished from Greenfield because the shots are longer in duration, and her face becomes visible) moves into a space with a white background, and Greenfield enters a black space. Greenfield also ventures closer to the camera, becoming not only a blur but several times seeming to become a ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Flesh Into Light: The Films of Amy Greenfield

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Beginnings

- Chapter 2: Planning and Discovery

- Chapter 3: Holograms and late 1970s

- Chapter 4: 1980s and Antigone

- Chapter 5: 1990s: Performance and the Cycles of Light

- Chapter 6: 2000s: The Body Songs

- Chapter 7: 8 Perspectives

- Appendix 1: Filmography of Amy Greenfield through 2009

- Appendix 2: Fragments: Mysterious Beginnings and Fragments: Mat/Glass and One O One

- Appendix 3: Raw-Edged Women and MUSEic of the Body

- Appendix 4: Six notions and a question about my work in video

- Appendix 5: The Clock Tower

- Appendix 6: Bibliography

- Appendix 7: Greenfield on Greenfield