eBook - ePub

Habitus of the Hood

- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

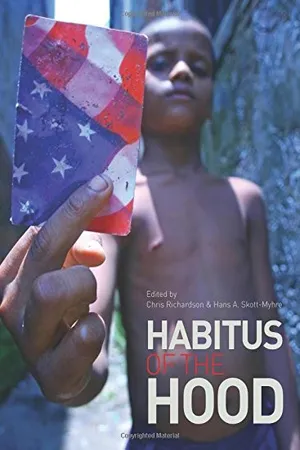

Habitus of the Hood

About this book

Since the 1990s, popular culture the world over has frequently looked to the 'hood for inspiration, whether in music, film, or television. Habitus of the Hood explores the myriad ways in which the hood has been conceived—both within the lived experiences of its residents and in the many mediated representations found in popular culture. Using a variety of methodologies including autoethnography, textual studies, and critical discourse analysis, contributors analyze and connect these various conceptions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Habitus of the Hood by Chris Richardson, Hans A Skott-Myhre, Chris Richardson,Hans A Skott-Myhre, Hans Skott-Myhre, Chris Richardson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

Chris Richardson and Hans A. Skott-Myhre

The habitus of the hood

“The hood” embodies both the utopian and dystopian aspects of low-income urban areas. It represents an awareness of community, an enclosed space in which residents are united in their daily struggles. It also signifies an isolated, marginalized, and often-criminalized space that appears frequently in popular media representations, legal discourses, and public discussions. The popularity of the word hood, here slang for neighborhood, is generally associated with the emergence of hip-hop culture in the 1980s. The word also became highly visible after a series of “hood films” were produced in the early 1990s. The most popular of these films were John Singleton’s Boyz N the Hood (1991), Ernest Dickerson’s Juice (1992), and the Hughes brothers’ Menace II Society (1993). Today, however, “the hood” signifies much more than the young, predominantly black subculture in North America from which it originated. The chapters in this collection demonstrate that the hood has now expanded to Europe, Australasia, and many spaces in between, incorporating a plurality of ethnicities and subcultures as global capital and new media technologies collapse previous notions of time and space.

The concept of the hood can be both liberating and limiting. Residents associate certain life possibilities with their surroundings, which they internalize and act upon. This conception has both real and symbolic consequences for individuals inside as well as outside the hood. It pushes people in certain directions and creates values, practices, and judgments that are often shared within similar communities. As the saying goes, “you can take me out of the hood but you can’t take the hood out of me.” This internalizing of one’s environment, its implications, and its representations, are what we seek to interrogate in the following chapters.

We argue that Bourdieu’s (2007 [1977]) notion of habitus, a “system of durable, transposable dispositions” that form “principles which generate and organize practices and representations” (p. 72), is a valuable theoretical tool for analyzing the hood. While the term habitus, a Latin word meaning habitude, mode of life, or general appearance, may be as old as the ancient philosophers, we use the term as promoted by Bourdieu, particularly in Outline of a Theory of Practice (2007).1 In this book, we also expand Bourdieu’s concept through a reading of Robin Cooper’s (2005) “dwelling place,” which she explains as “a kind of knowing one’s way about . . . [that] implies a freedom to move in some domain or other, which is more akin to sure-footedness” (p. 304). In addition, Cornel West (1999a) provides a useful distinction between hood and neighborhood, which he argues represents the difference between extreme individualism and collective identity. Finally, we approach the hood as a concept à la Deleuze and Guattari (1994), as a space that is perpetually becoming, a space constituted by “revolutions and societies of friends, societies of resistance; because to create is to resist; pure becomings, pure events on a plane of immanence” (p. 110).

This collection explores how the hood is conceived within the lived experiences of residents and within mediated representations in popular culture.2 Whether fictional or documentary, representations of the hood embody potentialities. Like habitus, the hood is “a past which survives the present and tends to perpetuate itself into the future” (Bourdieu, 2007, p. 82). The relationship of individual subjects with the social conditions in which they live is explored in this collection through methodologies such as (auto) ethnography, textual analysis, and critical discourse analysis. By examining this relationship through different lenses and with different focal points, we illuminate the similarities between (neighbor)hoods while also examining the particularities of hoods populated by multiracial, multisexual, and multicultural families (Skott-Myhre, Chapter 2), youth along the Gold Coast in Australia (Baker, Bennett, & Wise, Chapter 5), and young women in the inner suburbs of Los Angeles (Nicol & Yee, Chapter 8). As Hagedorn (2007) argues, the elements of crime that were once considered part of the twentieth-century North American hood now inhabit “the global city.” In other words, confining “the hood” to cities like New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles is no longer accurate. One telling example of this change is evident in Wacquant’s (2008) introduction to his recent study of urban marginality. He begins by pointing out the similarities and differences between what can roughly translate as the global hood – the American ghetto, the French banlieue, the Italian quartieri periferici, the Swedish problemomrade, the Brazilian favela, and the Argentinian villa miseria. Evidently, while “the hood” may continue to hold distinctly American connotations, there is something in virtually every country on the globe that knows marginality, poverty, and stigma. We intend to address this expanded definition of the hood through our exploration of the hood as habitus.

Before turning to these studies, we would first like to explore what is at stake. How is the hood related to Bourdieu’s concept of habitus? Is there a clear difference between neighborhood and hood? Is the hood a spectacle or a dwelling place? In the following chapters, we reflect upon what these questions imply, how we might negotiate them, and the importance of such intellectual work. At a time when inquiries such as these can very easily be pushed aside by more “prestigious” or “empirical” work (often by individuals and institutions with no connection to hoods in their communities and who remain dismissive of such research tout court), this exploration is incredibly important. The publication of this book broadens the intellectual scope of previous arguments in the fields of cultural studies, sociology, critical pedagogy, and child and youth work. Perhaps, more importantly, it recognizes a situation that has been increasing in scope and severity over the last few decades. As transnational corporations and capital markets struggle to extend their reach and the middle classes that formed in the late twentieth century quickly dissolve, the hoods are becoming more populated (see Hollander & Hollander, Chapter 7), residents are growing more desperate, and youth are becoming increasingly frustrated. We feel this exploration could not be more important, necessary, and timely.

The hood as habitus

The forging of a relationship between individuals and their environments is an important and complex part of socialization. The experiences and attitudes one witnesses first-hand at home, on the streets, and in schools shape practices and beliefs that are likely to be repeated in the future. Bourdieu (1984) writes of this connection as a relationship “between the two capacities which define the habitus, the capacity to produce classifiable practices and works, and the capacity to differentiate and appreciate these practices and products” (p. 170). In essence, habitus is a cyclical – but alterable – series of behaviors that determines how individuals see and act within their environments. Bourdieu notes that “the ‘eye’ is a product of history reproduced by education” (p. 3). In other words, the way we see the world is learned. And we learn to see by participating and interacting within our communities. We might say, then, that habitus (re)creates the social spaces that we call hoods by teaching insiders and outsiders how to see it, classify it, work within it, and understand it.

The habitus of the hood plays a crucial role in teaching residents what is and is not acceptable, achievable, and dreamable. It “makes coherence and necessity out of accident and contingency,” writes Bourdieu (2007, p. 87). Habitus naturalizes the attitudes and behaviors of residents in particular areas, street corners, and meeting places and makes them appear natural, as if they were innate parts of our being. Habitus can also make certain practices seem inherent to the spaces in which they occur, as if these practices were only possible in these spaces and other possibilities for acting are out of the question. This aspect of culture, as situated in geography, is often confused for nature. Bourdieu’s concept allows us to recognize that these “essential” practices are the result of experiences, mediations, representations, and dialogues that have taken shape within these spaces. It is a “nature” that must be constantly reiterated as “natural.”

Habitus is a way of seeing and acting that links certain groups in society. While all individuals form a habitus, this acquired skillset is not always the same. The experiences of one resident in one neighborhood can be very different from a resident of another neighborhood, even within the same city. What one sees and looks for may be completely different. The practices of one group may even be incomprehensible to others. For example, in Menace II Society (1993), the character O-Dog is famously described by his friend Caine as “America’s nightmare: young, black, and [does not] give a fuck.” But what does this mean? To an affluent, white resident of Beverly Hills, this description might provoke fear, indicating that O-Dog, as a young person, is reckless and rude; as a black person, is uncultured and prone to violence; and, finally, as someone who “doesn’t give a fuck,” he may be seen as disrespectful – particularly of private property rights. All these characteristics are negative and threatening to mainstream values – to mainstream habitus. Why one would adopt these behaviors may be baffling to the average person. On the other hand, to O-Dog’s friends, this description may be flattering. As a young person, he could be seen as energetic, passionate, and unbroken. As a black person, he can be viewed as conscious of racial prejudices and protective of his friends and family. And as someone who “doesn’t give a fuck,” O-Dog speaks his mind, regardless of the consequences. In other words, O-Dog is unlike those who have become reliant upon social norms; those who have according to West (2008) become “well-adjusted to injustice” (p. 16). O-Dog is not afraid to lash out at oppressors, to take what he feels he is entitled to, and he does not hesitate to challenge others. In most hoods, these are admirable qualities.

We are not arguing for or against O-Dog and the group of young, black men that he represents. What this example highlights is the difference between people in various communities and the conflict between the ways many of them see the world. Because habitus is a naturalized way of thinking, we tend to assume that our habitus is the only habitus that exists. O-Dog is raised within a community – Watts, California – in which attributes such as toughness are privileged and respected by his peers while traditional Judeo-Christian values like patience and “turning the other cheek” are not as admirable – in fact, those traits are more likely to get one hurt. Bourdieu’s concept of habitus helps us understand why this is so.

The fact that people within various communities tend to share values, practices, and beliefs means that our experiences within a certain space are often similar enough to create a sort of group habitus. Bourdieu (2007) argues that habitus presupposes a “community of ‘unconsciouses’” (p. 80). Each collective habitus is a product of events and circumstances that become naturalized and therefore unrecognized (i.e., unconscious) in the minds of community members. O-Dog is no more natural than the law-abiding, affluent, white person we hypothesized above. The only thing that is natural is the ability to form a habitus in which members of a community act in a sort of “regulated improvisation” (p. 79). One way of thinking through this idea is with the metaphor of a game. The rules of the game can be different in any community. But every community plays a version of this game.

People learn how to act as they grow within their environment. Each individual comes into contact with people and situations that illustrate the “right” way and the “wrong” way to do things. Seeing this repeated over and over again eventually guides residents toward common practices, allowing them to know what to expect from situations before they arise. We develop a set of linguistic and cultural competences through this process much like the way accents are formed between people in various parts of the country. Because neighbors are used to speaking with each other, they begin to sound similar. This is why no one thinks of themselves as having an accent. Accents are something other people have. One only notices the difference in dialect when traveling or when strangers come to town.3

Local practices are often internalized and repeated without ever being consciously examined. By continuing to act in a way that seems completely natural and unquestionable, individuals perpetuate these practices within the community. Bourdieu (2007) refers to this as “the dialectic of the internalization of externality and the externalization of internality” (p. 72). People internalize the culture of their surroundings. Simultaneously, these actions influence the characteristics of their neighborhoods. One’s hood does not determine how one acts, nor does one’s action determine the hood. Together, however, a symbiotic relationship arises and customs and practices become diffcult to separate from the communities in which they occur. Thus, Bourdieu (2007) writes about “a community of dispositions” (p. 79). Although not everyone experiences the same events, and therefore generates a different habitus, growing up in a similar class, with similar education, similar ethnic backgrounds, and similar values means that similar habituses are likely to develop. This is why we can talk about the hood as a collective habitus, even though individuals maintain their capacity to act differently, to challenge norms, and to think for themselves.

Hood or neighborhood?

We do not use the term “hood” to specifically denote a space with negative or positive connotations in this collection. It may bring up a whole web of connotations, but the only characteristics that make a hood a hood for us is the marginalized relationship it shares with the mainstream; the working-class or sub-working-class existences of the majority of its residents; and the often high population of visible minorities living within it. In this way, the hood is a particular kind of neighborhood.

The first lines of Lance Freeman’s There Goes the Hood (2006) may provide the best description of what the hood has become in popular culture:

The Ghetto, the inner city, the hood – these terms have been applied as monikers for black neighborhoods and conjure up images of places that are off-limits to outsiders, places to be avoided after sundown, and paragons of pathology. Portrayed as isolated pockets of deviance and despair, these neighborhoods have captured the imagination of journalists and social scientists who have chronicled the challenges and risks of living in such neighborhoods.

(p. 1)

This may be an accurate account of modern perceptions of the hood. In this book, however, we hope to probe more deeply the ways in which the hood is different from and similar to common notions of neighborhood and community. Clearly, the answer is not a simple matter of definitions nor causes and effects. As Freeman indicates throughout his book, the hood often teeters between self-destruction and upward mobility. In Lawrence Fishburne’s famous speech on gentrification in Boyz N the Hood (1991), he ask...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Part I: The Hood As Lived Practice

- Part II: Representing the Hood in Music, Film, and Art