- 188 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

To what extent is our time characterised by the 'digital'? Does it announce a bright new age of technological progress, or is it not much more than a marketing tag for manufacturers? What is clear is that much of the cultural theory we have so far accumulated is showing signs of strain as it struggles to cope with the global dynamics of the 'wired world'. This book offers a timely intellectual strategy that may help us comprehend the contradictions and apparent paradoxes of our immediate cultural climate. Using the metaphor of an organic membrane to show how things can be both separate and connected, The Postdigital Membrane explores the triad of imagination, technology and desire as they play upon each other – and us. In doing so it tries to offer fresh insights into the deeper problems of intelligence, reality and being human in order to map the emerging consciousness of the postdigital age.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Section Six

PROPOSITION:

The practice of art consists in arranging matter so as to add (extra) significance to it.

A plate of food scraps

If I distrust my memory...I am able to supplement and guarantee its working by making a note in writing. In that case the surface upon which the note is preserved, the pocket book or sheet of paper, is as it were a materialized portion of my mnemic [sic] apparatus, which I otherwise carry about with me invisible.

Sigmund Freud, A Note Upon the ‘Mystic Writing-Pad’

Rock art to Web art: Projecting the imagination

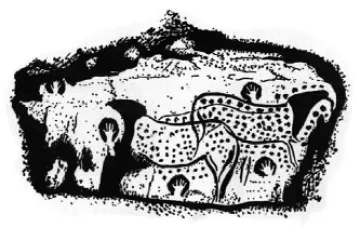

We are free to speculate about the function of images applied to cave walls and rock surfaces by distant cultures. Inevitably, we will be inclined to interpret them from the intellectual convenience of our present historical perspective, casting the light and shadows from our own candles and reflecting our current sensibilities. Whatever speculative interpretations we now place on these images there are a number of reasonably secure claims that we can make. First, these works are the product of human activity. Secondly, the beings that made them enjoyed a level of intelligence that we would recognise in ourselves (perhaps greater intelligence than we had previously imagined if recent theories about astronomical maps in the caves of Lascaux are to be credited). Thirdly, the paintings and carvings were not random deeds of mutilation or defacement but intentional creative acts arising from motives peculiar to the circumstances in which they were conceived. Whatever moved those ancient ‘artists’ is still the subject of academic research and open to debate (even if we do eventually make a proper time machine for James Cole there is no guarantee he will understand pre-historic motives). What these images do have in common with contemporary experience is that they demonstrate the impulse to modify what is around us through a combination of thought and action, collapsed into a single coherent process. It seems we have rarely been content to leave the world unchanged, perhaps believing that our survival depended on changing it. More than any other species we change our surroundings to suit our needs and we can look to any urban space to see there is very little that has not been altered by human intervention. Whilst this is not a revelation, it is a fact of foundational importance that can go unnoticed. Looking into an ancient cave reminds us of our persistent desire to modify the environment according to our imagination.

Palaeolithic Rock Painting

What we recognise in those rock artists of the Palaeolithic era is the impulse to integrate our mental and physical space, crossing that perceived divide through the agency of imagination. It may be that a sophisticated language faculty is the defining characteristic of humanity, but this is only one example of our desire to draw the world into ourselves and ourselves onto the world. In this sense there is a direct genealogical trail stretching across human history that is expressed today when people upload pictures onto their homepages. Such acts are examples of the attempt to imprint our personality (the sum of mental and physical activity) in an enduring medium that becomes subsequently accessible. In the process there is relay of imaginative impulses that pass from one side the human membrane to the other, reminding us of the indivisibility of the two spheres of human existence (internal and external).

Significant matter

It is often the case that art, regarded as imaginative entelechy, transcends the internal and external spheres as it absorbs the quotidian, the concrete and the transcendental. An example exists in the Annunciation with St. Emidus by Carlo Crivelli hanging in the National Gallery in London. This painting has been there since 1864 when it was presented by Lord Taunton in a philanthropic act which linked charity with the material value of art. It was an apt choice since the painting itself mixes the earthly with the divine. Today it has a different purpose, surrounded as it is by art in the National Gallery of a European capital. But during 1486 it was intended for the church of Saintissima Annunsiata in the town of Ascoli Piceno and since then its meaning has been inflected more by other paintings and political and economic events than the whispered confessions of the faithful in a provincial church. It is essentially a highly accomplished, carefully constructed statement, designed to be read and understood in conjunction with the New Testament, candles and chants.

Art as a connection between discontinuities

In a mise-en-scène more befitting James Cole’s adventures, the carpet on the balcony in the painting connects the past and the present by depicting the contemporary practice of hanging carpets on Good Friday. Inside the house the symbols of a good woman abound, her house is tidy, the plates stacked, bed made, cushions ordered and so on. In all respects it is a purposeful composition which celebrates contemporary technique by including two trompe l’oeil fruits attached to the surface — an apple to signify the fall and a gourd to symbolise the husk of the human body. It is because of the evidence of this careful design that we are surprised by the Angel’s partial interest in the Virgin and the utter indifference shown to her by the patron Saint of the town, St. Emidus (perhaps it is because she has yet to be famous). This sweet-faced man is holding a model of the town of Ascoli Piceno, the very town that provides the setting for the annunciation. We know that on March 25th 1482 news reached the town that the Pope had granted a certain measure of self government to Ascoli Piceno and that the painting was commissioned to celebrate the two annunciations, that of the angel and that of the Pope. Here past and present, material and ethereal, private and public, local and universal are fused in a masterful exposition of contemporary art practice. Oil, pigment and cloth are skilfully arranged so as to semi-permanently encode the imaginative excitement of these events. Stylistically so distant from the cave paintings of Lascaux, this image merely retreads the desire inscribed on the walls in previous ages and in many distant places.

The functions of artistic expression

In trying to account for the function of artistic expression as a near-universal phenomenon we can cite a wide range of possible motives: serving as an indicator of status or class, focusing religious sentiment, tribal identification, supplying a commercial market, decorative adornment, recording information, passing on knowledge, and so on. Whilst it would be simplistic to attribute something as complex as artistic production to a single determinant it may be that the various functions cited have something in common, or at least an inter-related significance; that is, the compulsion to manipulate and organise matter such that it evokes something other than it is. This compulsion can puzzle even accomplished artists:

It seems strange to me that someone thought of making marble statues. I understand how you could see something in the root of a tree, a crack in the wall, in an eroded stone or pebble. But marble? It comes off in blocks and doesn’t evoke any image. It does not inspire. How could Michelangelo have seen his David in a block of marble? Man began to make images only because he discovered them nearly formed around him, already within reach. He saw them in a bone, in the bumps of a cave, in a piece of wood. One form suggested a woman to him, another a buffalo, still another the head of a monster. (Pablo Picasso)

Brassaï, Conversations with Picasso

The factors of recognition and resemblance

The observation of small babies seems to confirm the immediacy with which we are able to re-cognise the content of a representation (a toy bear) and suggests such recognition is a primary cognitive faculty. Indeed, it may be so primary that it is prior to the faculties of comprehension or analysis, and therefore impervious to scrutiny. In which case, the search for its origins could only be a matter for informed speculation and theoretical debate. However, if we have any intellectual investment in the idea of evolution then we would be inclined to say organisms use their sensory apparatus to survive and gain reproductive advantage. For reasons that do not require elaboration here, the faculty of recognition (Latin: to know again) would have been of significant benefit to the development of our species. It has become clear through a number of psychological and physiological experiments that recognition is a significant part of sensory processing, that is, the correlation of sensations with learned or innate perceptions. It would seem sensible that such a complex would respond in a similar way to a stimulus correlating to a given object which was not actually the object perceived. For example, we may see a black bag on a chair and think it is a cat — a case of mis-recognition. Nonetheless, for the time that we perceive it as a cat it is a cat, as far as we are concerned, and if we are frightened by cats we will be genuinely afraid of the bag until we see it for what it actually is. Likewise, through similar action of stimuli and perception, we can wilfully perceive equivalence in objects that share perceptual qualities — a mountain range might suggest a face in profile or a tree stump may look like an old man — a case of resemblance. The critical difference between a mis-recognition and a resemblance is the mis-recognised object starts by apparently being one thing and then becomes (almost irredeemably) another — the two perceptions are mutually exclusive and consecutive. Meanwhile, the resembling object can both be itself and be like the thing it resembles — the two perceptions are mutually exclusive but oscillatory.

The factor of representation

The processes of mis-recognition and resemblance are necessary components of representation — the phenomenon whereby matter or energy is intentionally arranged so that we perceive something that is absent. Representation demands that we (almost permanently) mis-recognise the material from which the representation is made because the material resembles so strongly something other than itself. With visual representation, as for example in a statue, an object resembles more closely something it is not (a figure or animal) than something it is (stone or wood). In this instance the materiality of the sculptural medium is subordinate (by repression and perceptual delay) to the representational significance of the figure — the appearance of what is absent over-rides the actuality of what is present. In the drawing below we recognise a human head as a consequence of an arrangement of ink marks that are all but invisible at the moment of perception.

In this drawing the factors of mis-recognition and resemblance collectively inspire the representation of an ‘absent’ head (which is also a mark on the page)

The operation of the mark

Whilst not all representations are made with marks (other technologies such as electron streams are available) mark-making, along with carving, is undoubtedly one of the primordial ways of arranging matter so as to endow it with extra significance. In being so arranged, the representational mark renders the conscious impulse that created it, an impulse that can then be relayed back to a viewer (perhaps intact) when perceived and recognised. Hereupon the mark itself virtually disappears, or at least becomes transparent, inasmuch as we apparently see it for what it purports to be rather than what it actually is (as in the picture above). We are culturally bound to mis-recognise the mark for what it resembles, to imagine an absent object or idea in its place. Yet, as with the operation of the Mystic Writing-Pad, a significant trace of the mark itself (or the object being represented) is never entirely absent from the picture.

The envaluation of the mark

The imaginative operation of mis-recognition and resemblance, as they conspire to produce representations, normally requires that the technology of the mark remain largely transparent. If we read the drawing above as merely a squiggly line of ink then we would be seeing only the mark itself, presented through the technology of print. Yet also apparent within the technology of marks are assumptions about the cultural value of the imaginative impulses they relay: there are varying qualities of print. Dry mark-making invariably involves a soft smooth material — lead, graphite or wax — being drawn over a relatively hard, textured material such as paper or canvas. This kind of mark is the consequence of some of the soft material being abraded, and the detritus from the process becoming absorbed in the irregularities of the surface of the support. Erasure is restricted by the absorbency of the support, which normally means subsequent clean mark-making is rendered impossible. The blackboard works in a somewhat different way. A hard smooth surface supports the grains of a compressed dust that are deposited when the pressure on the chalk, as it is dragged across the surface, exceeds the pressure exerted by the binder that holds the grains together. The adhesion of these grains to the surface of the board is a consequence of attraction at the molecular level and residual moisture in the chalk, which draws water from the atmosphere. Since no deep absorption occurs on the surface the dust particles can be relatively easily removed. By sacrificing a degree of permanence then, erasure and correction are, to all intents and purposes, infinite. Such fluidity encourages a type of imaginative improvisation that is able to erase its immediate past without regard its own position in the future. The radical feature of the blackboard was that its use acknowledged the impermanence of some marks and what they represented, implying therefore, the possibility of imaginative flux, since the marks that embodied imagination were, themselves, reconfigurable. The device has frequently been used as a visual metaphor for abstract thought in motion — Albert Einstein was famously pictured with a blackboard full of scribbled equations. For most people, of course, his mathematical marks remain almost entirely opaque, which only serves to reinforce their fleeting purpose. The mark that is absorbed into the support, by contrast, has the virtue of permanence which, thereafter, permits it, along with the imaginative activity it represents, to enter the temporal order of matter and gain an historical (and often legal) validity. As such it resists becoming ephemeral, to the satisfaction of those who deny the present. This materiality of the mark reflects the general trend that privileges rigidity over fluidity, inscription over improvisation. This is further demonstrated by our consignment of the blackboard to the heritage-park and our huge investment in permanent archives and galleries.

Light technology

Up until the mid-nineteenth century, viewing representations, such as paintings, by daylight would have been the exception rather than the rule. From cave-painting to church icons to courtly galleries, flames were used in one form or another as artificial light to illuminate the marks that rendered the representations. Yet, paradoxically, the least visible constituent of the imaginative process of visual representation is light itself. In the case of artificial light, the radicalism of the candle is easily overlooked. Prior to the candle, light was generated by burning sticks. The best were those impregnated with resins and these burned to ash as they gave illumination. In a startling inversion of the dynamic, the oil lamp, burning vegetable oils or tallow (animal fat) used a crude wick which was not consumed in the production of light, the fuel was exploited whilst the conduit was everlasting. Both means were somewhat unpredictable, inefficient, and generated fumes which limited their applications. The candle differs from the tallow lamp in an important and radical way. Although both draw inflammable oils into a flame by capillary action, the candle uses the heat of the flame to liquefy the oil and this renders it safe and portable, with the added advantage that latent light could be stored for long periods in a compact and relatively stable form. In 1783 a new kind of wick was developed which fed oxygen into the centre of the flame and enabled all the carbons to be consumed in the combustion processes giving increased luminance and less fumes. An ingenious refinement was introduced by the addition of a filament that contracted on burning causing the wick to curve and its tip to touch the hottest part of the flame and burn away rather like the resinous stick did. But for this arrangement the flame would become smoky as the wick became longer. Most of all, however, the candle was not just a ‘super stick’ in which the fuel to waste (noise to message) ratio was spectacularly reversed, it was an efficient source of light that could be mass produced and distributed within the circuitry of an emerging industrialised society. Candles quickly became essential paraphernalia to the activity of both making and seeing art. Yet, in the same way that the mark becomes transparent at the moment it refers to something other than itself, candles remained largely invisible as attention focused on the objects they illuminated rather than the imagination embodied in the remarkable te...

Table of contents

- Cover page

- Half title

- Title page

- Copy right

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Section One

- Section Two

- Section Three

- Section Four

- Section Five

- Section Six

- Section Seven

- Section Eight

- Section Nine

- Section Ten

- Notes

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Postdigital Membrane by Robert Pepperell,Michael Punt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.