![]()

Part 1 – The Constituent Disciplines of Cognitive Science

1. Philosophical Epistemology

Glossary

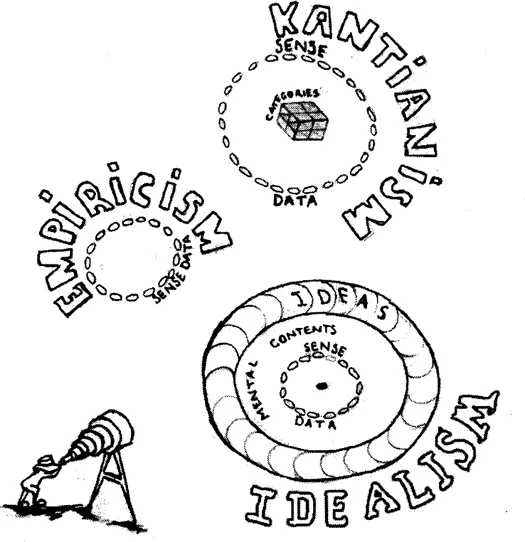

Empiricism states all knowledge comes from the senses: its opponents are rationalists and idealists.

Rationalism states that all knowledge comes from mental operations.

Idealism states that knowledge is essentially a trickle©down from a world of ideas.

Innatists believe that knowledge is genetically or otherwise inherited. Their natural enemies are also empiricists.

Kantians believe that knowledge derives from sense-data mediated through mental structures which they call categories.

Conceptualists believe that concepts are naturally-occurring aspects of reality.

Nominalism states the opposite, i.e. that a concept is just a name.

Materialists hold that mental properties are in some way an aspect of matter.

Their allies are Reductionists, who won’t be happy until all mental activity can be reduced to description in purely physical terms.

There is also an eliminativist (another buzzword) tendency about this latter trio, who have as their common enemy:

Dualists, who hold that there is a spiritual principle at work in mind, together with the material processes and

Holists, who claim that there are whole-properties associated with any biological processes from the level of the cell upward, and who insist the same about mind.

Realists insist that knowledge is impressed in the mind directly by objective properties of the world. They hate Idealists.

Situatedness: The notion that all of Cognition is profoundly affected by the physical and social situation in which they take place. It is related to

Embodiment: The notion that Cognition can only be considered with respect to the co- presence of a body and also to

Mundanity: The notion that mind, body and world are different, but profoundly interrelated and can best be considered together.

Existentialism is the school whose slogan is “existence precedes essence,” i.e. we should attend to the necessary facts surrounding our immediate existence before launching into theory.

Reductionism attempts to describe mental activity in observable neural events.

Eliminative materialists attempt to do away with all the common concepts of “folk psychology” like belief and desire, describing these entities purely in physical terms.

The philosophy of mind deals with the analysis of certain psychological constructs. These include propositional attitudes, which are terms which relate subjects to hypothetical objects, e.g. “believe” in “X believes Y.”

Functionalism is the doctrine that mental processes have “multiple realizability,” i.e. it is irrelevant to their formal analysis whether they are run on my brain, your brain, a computer, or an assembly of tin cans. Functional equivalence thus falls under that category of equivalence analysis called

Figure 1.1

Token-token analysis, which is satisfied with demonstration of equivalences under some system of identification or other. In contrast, type-type analysis insists on the more stringent requirement of physical identity.

Intentionality: As originally formulated by Fr Brentano, it points out as a crucial property of mental states the fact that they point to objects. It must be clearly distinguished from any of the connotations of its colloquial association with “will.”

I refrain for now from attempting to define:

Consciousness

Being

Knowledge

The diagrams in Figure 1.1 all have a ring of beads representing disjoint sense-data. A solid ring represents structured sense-data. The inner space represents mental contents.

Mind has not yet been defined: where does it fit in these diagrams?

| 1.0 | What is Philosophical Epistemology? |

A short answer to this question is that it is the theoretical approach to the study of Knowledge. It can be distinguished, in these terms, from experimental epistemology which features in the remainder of the disciplines within Cognitive Science.

Philosophy (literally, love of knowledge or wisdom) has recently had a very bad press. As we shall see, it used to comprise disciplines like physics, chemistry and mathematics, all of which in turn broke away from it. At present, it sometimes looks like the exclusive property of two wildly antagonistic camps. The first camp, the analytic school, seem to hope through the analysis of language to analyze philosophy right out of existence and themselves out of jobs. The Continental school, on the other hand, is still concerned with the Big Questions like God and the Meaning of Existence. However, its members have a predilection for all-encompassing book titles like Being and Nothingness which can’t possibly live up to their advance publicity.

When Psychology broke away from Philosophy in the mid-nineteenth century to set up shop as experimental epistemology, people began to ask whether philosophy might not eventually reduce to the null set. The consensus is now that its best regarded as a method of rational inquiry which can do a useful task in making explicit some of the assumptions inherent in various aspects of structured human activity, or in general as rational inquiry in any field.

One such activity is Science. One task of a philosophy of Science is to compare the stated assumptions about the methodology of science with the reality. Moreover, it can prescribe on the basis of thorough analysis that which is likely to be a worthwhile area and/or method of investigation, and that which isn’t. A vast such literature has grown up around Cognitive Science (mainly in the Philosophy of Mind) and we analyze it at the end of this chapter.

However, we’re going to find philosophy useful for other reasons as well. Up to Piaget’s and Warren McCulloch’s (1965) early work, “epistemology” meant quite simply philosophical epistemology. In other words, historically speaking, philosophy is the area in which the problem of knowledge has been discussed. Philosophers lacked the experimental tools featured in the other chapters of this book; they had to find some way of systematically appealing to experience.

It’s fair to say that they didn’t come to many lasting, comprehensive solution to the problem of knowledge. However, we can learn a lot from the clarity with which they discuss issues of perception and cognition. They did manage also to ask the right questions. Having taken a position (e.g. empiricism) on those questions they often found themselves backed into a corner. It is when fighting their corners that they tend to be at their best. We’ll see this in particular in Hume’s response to Berkeley. One of the really important things about Cognitive Science is its ability, through the current availability of appropriate experimental evidence, to show how all these brilliant minds, though apparently greatly at odds, were in a sense correct.

The path this chapter takes is the following. First of all, we’re going to briefly look at the history of Western Philosophical epistemology. Secondly, we’re going to regroup by considering at length the central problem treated (i.e. the relationship between mind and world).

Thirdly, we’re going to examine the work of existentialist philosophers who had a view of this problem very similar to that emerging in AI.

Finally, we’re going to examine current controversies in the philosophy of mind which relate to Cognitive Science.

| 1.1 | The reduced history of Western Philosophy, Part I – The Classical Age |

The Reduced Shakespeare Company perform The Complete Works (Shakespeare, 1986) in one thrilling evening, culminating in a thirty-second Hamlet. The following pages are analogous. We’d better start, as we’ve a lot to get through.

To make things easier, we’ll ignore Oriental thought for the moment. The content of this section, then, is those schools of thought which originated in Greece around the seventh century BC, were preserved through the Dark Ages by the then great civilization of Islam and by Irish monks before coming to a later flowering through the rediscovery by Europeans in Islamic Spain of their own cultural heritage.

The first stirring of philosophical thought around the seventh century BC in Greek culture consisted of an attempt to grasp a single underlying principle which could explain everything manifest. The earliest suggestions for such a principle (from Thales and his followers) were the basic elements as conceived of at the time (earth, air, fire, water) the later suggestion of Herakleitos (or Heraclitus) was change, or fire. Let’s note that no distinction was made between the material and the mental, or knowledge and being.

Later came the Pythagorean school, with the first attempt at an abstract description of reality independent of its felt existence. The kind of experience which fueled their work is epitomized by the laws of musical harmony. There is a detected harmonious relationship between strings on an instrument which have certain simple mathematical relationships to each other (e.g. if one string is precisely double the length of another, its pitch is an octave lower). The insight that we can home in on an aspect of reality by manipulation of abstract symbols in this manner is still an exhilarating one.

Let’s call Pythagoras and his school the “Neats.” The “Scruffs,” or Sophists, were in the meantime teaching virtue, as they understood it. With Socrates, the hero of Plato’s dialogues, the Neat/Scruffy division falls apart. To know Plato’s world of Ideas is to be virtuous. The Good, True and Beautiful are one.

Plato’s schema, depending on one’s perspective, is one of the great intellectual constructs and/or one of the great pieces of self-delusion of all time. The world of appearances is flickering shadows on a cave wall. Reality is a set of other-worldly Forms, which objects in this world can somehow participate in or reflect and thus borrow some of their Being. Let’s note, parenthetically, that many contemporary mathematicians (e.g. Gödel, Penrose) still take these ideas seriously with respect to mathematical concepts: for example, what in this world is an infinite set?

It is said that everyone is drawn by temperament either to Plato or his pupil Aristotle. One huge issue that puzzled Aristotle is this; how many Forms are there? Is there a Form for a CS text? We see this issue again in AI.

The materialist/dualist war (it has all the characteristics thereof) is essentially part of Plato’s heritage. Recent pitched battles: Libet (1985) versus Flanagan (1992); Eccles (1987) versus all comers. If you contrast a world of Ideas with the actual world, the war is inevitable. Aristotle produced a framework in which this type of issue doesn’t arise. Substance, he argued, is form plus matter. Consider a biological cell. There are material processes going on by which the cell is a cell (i.e. by which it has its form as a cell). A statue is a more obvious example: the matter of the statue is that by which it has its form. Can we separate the material and mental in the brain in this way?

We consider this issue again presently. For the moment, let’s note that Aristotle was an insatiable collector of facts about everything that came across his path. This insistence on observation continued in Greece to Almcaeon and his school, which by the fourth century BC had located thought in the brain, and had at least a sketchy idea of neural functioning. Had a Hellenic Warren McCulloch connected this anatomical work with what was already known about electro-chemical plating, we might have had some very precocious Cognitive Science.

Let’s pause for breath for a moment. These themes have emerged:

• The search for a single underlying explanatory principle for all that is.

• The idea that abstract operations on symbols can inform about an external reality to which these symbols point. (If we incarnate these symbols in computer programs, we get what’s called the Physical Symbols Systems Hypothesis (PSSH).

• A notion that substance can be divided into form and matter.

Let’s again note that Philosophy was, up to this point, also the activities which we call Science, Politics and Theology. It has lost a lot of capital since then.

Had Greek thought maintained this breath-taking rate of progress, there would be little for us to do. We haven’t touched on the advances in Logic, Mathematics and Politics which occurred. However, as has been mentioned, the works of Plato and Aristotle were lost to the Western world during the dark ages. Before we fast-forward two millennia, let’s note one speculation of St Augustine, Bishop of Hippo in North Africa. Words name objects, and children learn language by correlating the word and its object. We’re noting this point because it’s (at best) incomplete, both as a theory of linguistics and developmental psycholinguistics.

| 1.1.1 | Scholasticism and the first stirrings of Modernity – Thomas Aquinas |

The reduced history of Philosophy would normally skip the four-hundred years between Aquinas and Descartes. This is particularly the case because Aquinas is normally identified as the foremost defender of the Roman Catholic faith. In turn, this activity may seem to involve aiding particularly nasty South American dictators while condemning the sexual act in all its manifestations.

In fact, Aquinas is relatively blameless on these points. He is important to Cognitive Science for two reasons. First, he provides the first great medieval treatment and development of classical philosophy. Secondly, he and his modern “Thomist” followers (e.g. Lonergan, 1958) have much to say on the act of Understanding.

Thomas Aquinas joined the Dominicans against his father’s wishes, and read Aristotle contrary to the stated wishes of his contemporary church. He seems to have suffered from bulimia. Eventually, a large piece had to be cut out of the table so he could sit at it!

His first great contribution to philosophy is on ontology i.e. the problem of Being (what is), what different types of Beings there are. This problem manifests itself as the mind/body problem in CS. Aquinas’s solution is worth looking at for this reason.

Aristotle had no distinct concept of existence to complement his notion of substance. Aquinas, in common with philosophers of his time, attributed different vital principles of existence to beings at different levels of evolution. For example, a tree had a vegetative “soul.” This is not the main thrust of his argument: however, let’s note that these kind of notions are re-entering biology under the heading of “entelechy,” and they cast welcome mud into the deceptively clear waters of the monism/dualism debate.

Aquinas asks us to look at a person or anything which exists. He distinguishes the following:

1. That which is.

2. Its existence, which it possesses by virtue of an act of existence.

3. Its form, which it possesses by organizational patterns in its matter.

Thus we have a form/matter distinction as well as an issue of the potential for existence being fulfilled by an act of existence. Instead of the Cartesian mind/matter dualism we are going to confront later we now have a trio of substance, act and potency.

Moreover, the notion of substance allows us to speak of the form, as distinct from matter, of all biological entities, including mind. Much effort has been expanded on attempting to show that either monism or dualism is correct (e.g. Libet, 1979, versus Churchland, 1988). The position of this book is that the ontological issue is a great deal more complicated.

Thomism has much to say about Understanding. For its followers, understanding is about more than mere cognition: it quickly, in turn, structures one’s ethical concept, then one’s concept of God. Thomism sharply distinguishes understanding, which has as its object an idea, from imagination, sensation, perception etc. It is from analysis of the act of Understanding that the whole of Thomist philosophy gets its main thrust.

And so on to modern Thomists. The major figu...