![]()

Part 1

2. Chaussee Strasse: the Last Place

In the vast ‘city’ of art and possibility the Brecht house was at one time an exciting house to live in.

(Richard Foreman, ‘Like First-Class Advertising’, drive B: brecht 100)

The interior is not only the universe but also the etui of the private person. To live means to leave traces. In the interior these are emphasized. An abundance of covers and protractors, liners and cases is devised, on which the traces of objects of everyday use are imprinted. The traces of the occupant also leave their impressions on the interior. The detective story that follows these traces comes into being.

(Walter Benjamin, ‘Paris, Capital of the 19th Century’)

Sometimes all that remains of the past is a name – it becomes the connective space, the passage to other experiences.

(M. Christine Boyer, The City of Collective Memory)

Staging Brecht

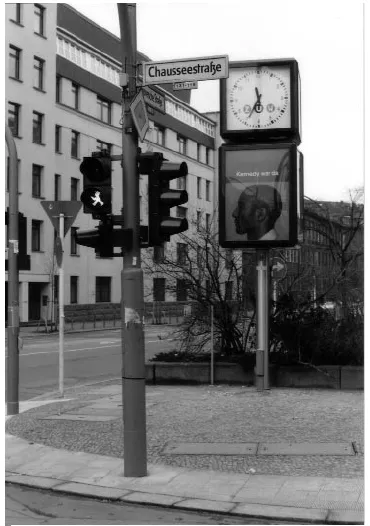

Feeling lonesome and bereft I go round to Brecht’s, a man who knows about migration. A friend in exile. The house, which incorporates the archive, is at Chaussee Strasse number 125 in Berlin’s Mitte district. That’s right in the centre of the city, as the name suggests. A centre called centre. The folk there, the attendants of the Brechtian habitat, tell me he is next door at number 126. That’s the funny thing about Berlin. It’s not odd and even numbers on respective sides of the street. Instead you might begin at one corner, at number one, say, count your way consecutively up that side of the street to the end, and then come back down the other side. On a long boulevard like Prenzlauer Allee, for example, it means number one ends up being opposite number 249. Of course, you don’t actually have to trudge laboriously up the whole length of one side and down the other till you find your number because there are indications on the street signs as to which numbers correspond to a particular block – unless they’ve been stolen, which is admittedly frequently the case.1 Eventually you get the hang of it, but just to help matters along, not all of the city necessarily conforms to this pattern. The streets around the Kollwitz Platz area immediately adjoining Prenzlauer Allee, for instance, operate an odd/even dichotomy. So, whenever you’re hunting for an address in Berlin – which, even as a native in a metropolis of some 3.5 million inhabitants, you frequently find yourself doing – there is always that moment of hesitation as you peer at the numbers on buildings: which system am I in here? I’ve attempted casually to uncover the historical reasons for the numbering discrepancy, but it seems that the highly delicate political issue of changing street names – to which I’ll return – has dominated to such an extent in Berlin that no-one seems particularly alive to the matter. The one thing you can say, as the example given shows, is that neat explanations of it as the relic of a former East-West division are misplaced.

2.

The other odd thing about Brecht being next door at number 126 is that it’s a cemetery, the Dorotheenstädtischer Friedhof. I know he’s dead, and the dead get buried in cemeteries, but do the latter customarily have numbers? My blind spot perhaps. (Thinking about it, though, maybe they should have several thousands.) Still, that’s where he is, along with Helene (his wife), Hegel (the philosopher) and Heiner (Müller, that is, the writer and director, who hasn’t been there long, of course). But let’s not begin with endings. Before paying a visit to the cemetery, I had an appointment to be taken on a guided tour of Brecht’s house. I was curious about this, not so much in expectation of what I might discover about the writer – I had in any case ‘done’ this tour twice in the past – but what the guide would be like. Some things I’d already picked up on, you see. When I’d made the appointment the previous day, the person to whom I had spoken on the phone had said, ‘Yes, we can fit you in at eleven o'clock. It’ll be a young 30 year old woman showing you round’. A strangely intimate volunteering of information it seemed to me. It’s not as if we were meeting one-to-one at a railway station where identification might have been a problem. All it needed was for her to add, ‘Her name’s Candy, by the way’. As far as I could tell, though, there was no erotic spin to it, no deliberate attempt to make the prospect of the visit appear more enticing. On the contrary, it seemed utterly matter of fact: this is what you’re getting.

But then maybe I was judging the situation by my two previous visits, one during the last years of the GDR, the other not long ago in 1998. Both had been characterised for me by that sense of a sober, sincere, ‘truth-to-materials’ consolidation of the Brechtian imago which the Berliner Ensemble was repeatedly taken to task for after his death in 1956, and which the British dismiss easily as humourless.2 I distinctly remember the guide two years previously – an older one, if we’re going to be particular about age – lamenting the fact that televised productions of Brecht were only ever shown on late-night TV these days, that being a pity since surely he still had so much to teach us. Everything for the modern generation – though she may well have meant ‘Western’ – seemed to be about fun, she complained, actually using the English word. Perhaps, then, the phone call had carried some sort of concession to changing times: not just a youngish person, who would barely have been out of school when the Berlin Wall collapsed, and who may therefore have a refreshing, if not cheeky, take on Brecht, but also a woman who would be bound to hold a robust view on the controversial likes of Professor Fuegi. In his biography The Life and Lies of Bertolt Brecht (1995), he attempts to discredit Brecht as, in Willett’s words, ‘a pig of variable sexuality who mastered his women collaborators by seducing them, and thereby got them to write a great part of his works’ (1998: 194).3

3.

As it turns out the 30 year old woman’s performance is remarkable above all for its speed of delivery. Belying her interest in the situation, she rattles off her lines to our little group as if she had a train to catch. However, she is a lot freer than her predecessors with the Brechtian legacy, eager to portray the writer precisely as fun-loving, as well as witty, and, in what seemed like a conscious move to counter charges of manipulation and domineering egotism, as rather reserved in company – more polite and a good listener. The mischievous, charming sides, moreover, viewed mistrustfully by some as just the characteristics masking his unpleasantness, particularly in relation to women, are passed off harmlessly in an amusing anecdote about the flux and flow of people in his house. Apparently, Brecht was very keen on the two exits and entrances. It allowed certain visitors to be kept apart, one lot being seen off furtively through one door before the next was greeted at the other. (What more would you expect from the author of such models of high farce as The Good Person of Setzuan ?)

Of course Brecht’s house is also Helene Weigel’s, the Berliner Ensemble’s most celebrated performer, who continued living there until her own death in 1971. She had kicked him out of their villa at Weissensee in the northeastern part of the city when he called her a lousy actress once too often, according to the guide.4 Nothing to do with ‘all his women’, she stresses, and I wonder how she would have come to know that. Surely not being taken seriously as a working woman would have represented some sort of final straw in the light of the validity Brecht accorded his other female ‘collaborators’. Eventually he persuaded Weigel down to Chaussee Strasse, but they occupied for the most part different sections of the house.5 This was 1953, around the time Brecht was finally given his own theatre building, the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm, about ten minutes walk down the road towards Friedrich Strasse station. Not that you would have seen Brecht dead walking down Chaussee Strasse. His love of cars is legendary.

Weigel used, in fact, to occupy the second floor of the house immediately above Brecht but moved downstairs to the ground floor after his death. The presentation of her domain is all matronly domesticity. Never mind that she was the Intendant (or artistic director) of the Berliner Ensemble, as well as its leading performer, which put her on a higher income from the theatre than her husband as it happens. There’s a spacious bedroom with one of those prominent nineteenth century stoves typical of Berlin apartments: tiled and larger than a full-size family fridge. (The guide during my visit in 1998 felt compelled to emphasise that Helene’s bed was a double one, as we could see; that separate bedrooms did not signify no sexual relations. She meant with Brecht, I presume.) A homely winter-garden functions as a living-room and looks on to a small but well-kept garden. And the kitchen is in cosy country style. Wherever you look in Weigel’s rooms it’s all well-worn wood, pewter, glass and earthenware; a paraphernalia of authentic antiques: hand-crafted furniture, crockery, vases, jugs and rugs. The only apparent gestures towards modernity: a Dalìesque Bakelite telephone (without the lobster) and, as one witness puts it, a ‘pre-Sputnik era television set’ (Hooper 2000).

Nobody dares to say, it seems so corny, but Weigel’s apartment really does appear like the staging of the home the nomadic Mother Courage would have had – despite a time difference of three centuries – had she not spent her life dragging a cart loaded with all manner of ‘useful’ nick-nacks around the European theatre of war. One of Brecht’s late poems, ‘Weigel’s Props’, refers to his wife’s predilection for choosing ‘the objects to accompany her characters across the stage’ according to the same principles with which the poet picks ‘the exact word for his verse’. As the poem goes on to observe: ‘Each item [...] selected for age, function and beauty/By the eyes of the knowing/The hands of the bread-baking, net-weaving/Soup-cooking connoisseur/Of reality’ (1976: 427–8). Brecht’s appreciation of Weigel’s talent is expressed in terms which neatly typecast her as the ‘natural domestic’. The Weigel recipes – her husband’s favourites – served up in the Keller Restaurant of the Brecht House represent the final endorsement of that perception. They’re called Versuche – the name given to Brecht’s collected ‘experimental writings’ pre-1933 – but culinary theatre might have been more accurate.

Despite my inner impulse to contradict or at least sniff at everything I’m being told, I realise I’m also enjoying this Brechtian Heimat-Klatsch, this ‘opera’. It’s like sinking into a hot, soapy bath. Wandering through these rooms, I experience a profound sense of familiarity and pleasure, of being in some sort of way ‘at home’. That’s not the consequence of having been here before but of something somehow being confirmed. It’s what you would expect, the Brechtian ‘always already’, a Gewohnheit or inhabitation. A diary entry of Walter Benjamin’s testifies to an afternoon spent debating theories of living with Brecht. The latter identifies a basic dialectic between a ‘convenient’ alignment to surroundings – what you might call the forming of a habitual habitat – and an attitude reminiscent of always being an invited guest in one’s own home (GS 6: 435–6). Here, the stage-managers from the Berliner Ensemble have discreetly set the scene: all props have been checked off, cue sheets are in place, audience in, final call, the performance can begin. If this is Brechtian theatre, though, it really is more like a culinary one, the flavour of Brecht, an appetising staging of a staging that proves as dialectical as synthetic pudding.

Brecht’s rooms are on the first floor and, above all, tell a story of work: books, manuscript cabinets, typewriters. A smaller study leads to another larger one, both overlooking different sections of the cemetery. In the former the chairs can be seen to be placed far apart from one another, because Brecht felt people thought more about what they said that way. So the guide says. Proximity encourages shooting from the lip. These rooms were, of course, one of the settings for the writer’s famous collective production sessions. Here, the guide feels compelled to make a general point about the active writing role of Brecht’s three main women collaborators Ruth Berlau, Elisabeth Hauptmann and Margarette Steffin (the last of which never experienced Chaussee Strasse6): of course they operated collectively, but Brecht was still the main mover. Without him nothing would have come about.

The emphasis in the apartment is on the authentic and simple to the point of austere, just to continue with the Brechtian myth. ‘Spare, proletarian splendour’, as the leftist politician Egon Bahr observed on a recent visit he made to the house (Henrichs 2000: 9). No half-curtains, but apparently Brecht did order one of his carpenters from the theatre to distress the floorboards so as to give them more of a worn look. They’re gone now, though. Dark brown as they were, they created a rather subdued atmosphere and were recently replaced by pine. (‘Wood was extremely hard to come by in the GDR’, the guide mutters.) With its large, southfacing windows and whitewashed interior, that gives the place a summery lightness, one epitomised by the simplicity and delicacy of the several Chinese parchment scrolls hanging on the walls. Confucius dominates in the main study, hovering majestically above a dark leather sofa as if it were his throne. Less imposing but somehow more resonant in a personal way, the scroll of The Doubter in Brecht’s modest-size bedroom. In exile at Svendborg in 1937 he wrote a poem about the character’s role as a check against complacency:

Whenever we seemed

To have found the answer to a question

One of us untied the string of the old rolled-up

Chinese scroll on the wall, so that it fell down and

Revealed to us the man on the bench who

Doubted so much.

I, he said to us

Am the doubter. I am doubtful whether

The work was well done that devoured your days.

Whether what you said would still have value for anyone

if it were less well said.

Whether you said it well but perhaps

Were not convinced of the truth of what you said.

Whether it is not ambiguous; each possible

misunderstanding

Is your responsibility. Or it can be unambiguous

And take the contradictions out of things; is it too unambiguous?

If so, what you say is useless. Your thing has no life in it.

(1976: 270–1)

Clearly it’s a poem which suggests that as a thinker and writer your work is never done because, apart from anything else, what you say has implications for those who would embrace it: ‘But above all/Always above all else: how does one act/If one believes what you say?’ (271). In fact, that line epitomises the performativity at the heart of Brechtian writing, the notion, reiterated by Willett (quoting Eliot), that ‘the poem is something which is intended to act’ (1998: 39). It does what it says, uses a question to assert an imperative of questioning, and inserts itself pragmatically in the context in which it supposedly takes place. In other words, it offers itself as instigator or respondent to a particular situation or moment, as a usable device. Brecht used poems like calling cards – as someone once said – sending out activating signals to whomsoever it might concern. There was in this an important plea for writing in the modern age of technology, one echoed, of course, in Benjamin’s preoccupations with a changing notion of ‘authenticity’ and the rise of (urban) alienation in his famous essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ (1999: 211–44). Boyer suggests that for Benjamin modernism ‘attempted to describe the crisis in perception that everyday experience created […] But these epistemological problems of perception, interpretation, and authenticity are no longer the dominant issues controlling postmodern thought in the era of electronic communication’ (1998: 492)....