- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

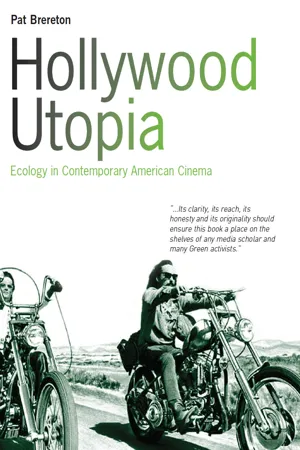

Utopianism, alongside its more prevalent dystopian opposite together with ecological study has become a magnet for interdisciplinary research and is used extensively to examine the most influential global medium of all time. The book applies a range of interdisciplinary strategies to trace the evolution of ecological representations in Hollywood film from 1950s to the present, which has not been done on this scale before. Many popular science fiction, westerns, nature and road movies, as listed in the filmography are extensively analysed while particularly privileging ecological moments of sublime expression often dramatized in the closing moments of these films. The five chapters all use detailed film readings to exemplify various aspects of this 'feel good' utopian phenomenon which begins with an exploration of the various meanings of ecology with detailed examples like Titanic helping to frame its implications for film study. Chapter two concentrates on nature film and its impact on ecology and utopianism using films like Emerald Forest and Jurassic Park, while the third chapter looks at road movies and also foreground nature and landscape as read through cult films like Easy Rider, Thelma and Louise and Grand Canyon. The final two science fiction chapters begin with 1950s B movie classics, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and The Incredible Shrinking Man and compare these with more recent conspiracy films like Soylent Green and Logan's Run alongside the Star Trek phenomenon. The last chapter provides a postmodernist appreciation of ecology and its central importance within contemporary cultural studies as well as applying post-human, feminist and cyborg theory to more recent debates around ecology and 'hope for the future', using readings of among others the Terminator series, Blade Runner, The Fifth Element and Alien Resurrection.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 HOLLYWOOD UTOPIA: ECOLOGY AND CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CINEMA

Prologue

Ecology has become a new, all-inclusive, yet often contradictory meta-narrative1, which this book will show to have been clearly present within Hollywood film since the 1950s. This study focuses particularly on feel-good films whose therapeutic character often leads to their being dismissed as ideologically regressive. By concentrating on narrative closure and especially the way space is used to foreground and dramatise the sublime pleasure of nature, Hollywood cinema can be seen to have within it a ‘certain tendency’2 that dramatises core ecological values and ideas.

The study is committed to a strategy of building bridges and creating cross- connections between film and other disciplines. In particular, the investigation draws on Geography (space/place, tourism and so on), Philosophy (aesthetics, ethics and ontological debates), Anthropology, Feminism and Cultural Studies, while maintaining close contact with the traditional literary and historical disciplines.

In the light of this cross-disciplinary approach, the first section of this introductory chapter sets the scene for an ecological investigation, drawing on a wide range of ideas and historical contexts, while the second section has a narrower focus, clarifying a methodology for film analysis to be used throughout the study. Within many blockbuster films, the evocation of nature and sublime spectacle3 helps to dramatise contemporary ecological issues and debates. Filmic time and space is dramatised, often above and beyond strict narrative requirements, and serves, whether accidentally or not, to reconnect audiences with their inclusive ecosystem.

As Bryan Norton puts it, environmentalism needs to educate the public ‘to see problems from a synoptic, contextual perspective’ (Norton 1991: xi). In this respect, Hollywood films can be seen as exemplifying, and often actually promoting, this loosely educational and ethical agenda, particularly through the use of ecological/mythic expression, evidenced in a range of narrative closures.

Introduction

The primary justification for this study is the dearth of analysis of the utopian ecological themes which pervade mainstream Hollywood cinema. There continues to be a preoccupation with narratology in Film studies, which often avoids the formal exploration of space. Coupled with this is the predominately negative ideological critique of Hollywood film, with many cultural histories predicating their analysis on Fredric Jameson’s view that ‘mass culture’ harmonises social conflicts, contemporary fears and utopian hopes and (more contentiously) attempts to effect ideological containment and reassurance. Relatively little academic effort is given over to understanding and appreciating rather than dismissing the utopian spatial aesthetic that permeates Hollywood film. This phenomenon will be examined most particularly through a close reading of closure in a range of Hollywood films from the 1950s to the present day, which can privilege a ‘progressive’ conception of nature and ecology generally.

In his dictionary of ‘green’ terms, John Button defines ecology and the growth of eco-politics as

a set of beliefs and a concomitant lifestyle that stress the importance of respect for the earth and all its inhabitants, using only what resources are necessary and appropriate, acknowledging the rights of all forms of life and recognising that all that exists is part of one interconnected whole

(Button 1988: 190).

The very idea of being ‘green’ only came into popular consciousness in the late 1970s, though since the 1950s ‘green’ has been used as a qualifier for environmental projects like the ‘green front’, a tree planting campaign popularised in America. The minimum criteria includes a reverence for the earth and all its creatures but also, some radical greens would argue, a concomitant strategy encompassing a willingness to share the world's wealth among all its peoples. Prosperity can be achieved through ‘sustainable alternatives’ together with an emphasis on self-reliance and decentralised communities, as opposed to the rat- race of economic growth (see Porritt 1984).

While the ‘ideological’ analytical strategy, focusing on power inequalities across class, gender and race boundaries, continues to preoccupy critical analysis of Hollywood cinema, there is little if any critical engagement with the more all- encompassing phenomenon of ecology. Yet, if so-called ecological readings are to remain critical and avoid degenerating into endorsing ‘naive’ polemics, they must explicitly foreground a variety of interpretations and perspectives, which question any universal utopian project.

To anchor this approach, notions of visual excess specifically drawn from feminist studies of melodrama illustrating a breakdown in ‘conventional’ patriarchal readings of film will be applied. By interrogating the over-determination of visual excess in films by Douglas Sirk from the 1950s, for instance, with their accentuated use of deep colours, together with heightened styles of acting, critics like Christine Gledhill (Gledhill 1991) explored how such films helped to sustain a mise-en- scène which stays with the audience long after the ‘tagged-on’ conformist closures. This critical position articulates how excessive and overdetermined stylistic devices serve to rupture and critique normative ideological readings, while also helping to produce a more ‘progressive’ representation of feminist values. This radical notion of visual excess will be reapplied, through an analysis of the narrative resolutions of a range of Hollywood blockbuster films, to expose their latent predisposition to excessively dramatise an ecological agenda.

Apparently unmediated and excessive representations of nature and landscape are consciously foregrounded in many Hollywood films discussed in this book. In particular, the film-time and space given over to this explicit form of unmediated evocations of eco-nature help to dramatise and encourage raw nature to speak directly to audiences, together with their protagonists, who finally find sanctuary from particular environmental problems. This expression of therapeutic sanctuary is often valorised over and above the strict narrative requirements of the text through, for instance, framing, narrative point-of-view and shot length. Rather than merely serving as a romantic backdrop or a narrative deus-ex-machina, these evocations of eco-nature become self-consciously foregrounded and consequently help to promote an ecological meta-narrative, connecting humans with their environment.

Together with the visual aesthetic, the protagonists in the films discussed will also be shown to embody various forms of ecological agency. This can be highlighted through the evolution within mainstream Hollywood cinema of what can be typified as a white, liberal-humanist, middle-class, ecological agenda across a range of genres whose filmic agency in turn serves to reflect mainstream attitudes, values and beliefs embedded in the ecology movement generally. This positive trajectory is at odds, however, with the influential criticism of Christopher Lasch, who notices a similar ‘hunger for a therapeutic sensibility’ but dismisses the impulse owing to its complicity with the normlessness of ‘narcissistic American culture’ (Lasch 1978: 7).

Titanic

A recent blockbuster success story like Titanic (1998) is helpful in signalling many of the often abstract preoccupations raised in this study. While Titanic appears, at the outset at least, to have very little to do with ecology per se, it can nevertheless be read using these lenses. Especially when interpreted in terms of myth, together with its engagement with textual excess and spectacle, the film provides a provocative forum for articulating an ecological agenda.

The most common question critics address in relation to Titanic is why such an ‘old-fashioned’ film has become so commercially successful. Gilbert Adair explains its fascination in terms of myth:

In the north Atlantic on 14th April 1912 at 11.40 pm, an immovable object met an irresistible force, a state of the art Goliath was felled by a State-of-the-Nature David, and our love affair with the Titanic was born

(Adair 1997: 223).

But why specifically do audiences want to experience (and re-experience) the visceral sensation of a ship going down in all its awesome horror and observe its passengers drown or freeze to death, especially while the heroine recounts her personal epic and fulfils her destiny with her dead lover by sending the most expensive diamond back to the bottom of the sea. A straightforward ideological reading would critique the film's apparent romantic renunciation of materialism in favour of ‘love’,4 which consequently problematises its feel-good, utopian expression.

However, adapting Adair's idea, one could also argue that mythical harmony, which can be translated into the language of deep ecology, has also been restored by the narrative. Audiences and protagonists experience how the past cannot always be successfully salvaged for financial profit, in spite of advanced technology. Conspicuous consumption is effectively critiqued when the most authentically evidenced valuables are destroyed and slowly disappear as the ship succumbs to the pull of the sea. Many of the films to be discussed similarly explore how primal elemental forces of nature finally provide a renewed form of balance within the narrative and become potent metaphors for a renewed expression of eco-praxis.

Extended moments of almost Gothic visual excess, often expressed through long static takes of a sublime nature that help resolve the narrative, also serve as an effective cautionary tale for audiences ruled by materialist values. Thomas Berry, for example, reads Titanic as a ‘parable’ of humanity's ‘over-confidence’ when, even in dire situations, ‘we often do not have the energy required to alter our way of acting on the scale that is required’ (Berry 1988: 210).

Speed, movement and action remain synonymous with the myth of America itself. This is very much evidenced by the popular male lead, Leonardo DiCaprio, standing on the prow of the fantasy ship with his hands outstretched like a benevolent deity as the camera triumphantly tracks down its length. Audiences at the end of the century appeared to crave such spectacle, as the allegory of this terrible disaster of a sinking ship testifies.5 Nature, in the form of solid frozen water and its equally potent liquid form, will inevitably claim its human victims. Metaphorically, the humans become sacrificial victims for the sins of capitalism, which tries to ignore the innate potency of nature.

While this film cannot easily be described as a conventional ecological text, nonetheless it does create a form of excess, which can be used to promote an ecological reading. This is embodied in the ship itself, which becomes the representational embodiment of nineteenth-century western industrial capitalism and is affirmed by many audiences’ response to it as a primary focus of identification and attraction. As one reviewer concludes, at the end of the millennium, ‘what grandeur and pathos the film possesses belongs to the mythic story of the shipwreck itself ’ (Arroyo 1998: 16).

Thus the (pre)modernist scientific certainties together with the hierarchical social controls, which include a fatal dismissal of the potency of nature, symbolically represented by the intractable icebergs, are finally called to account. From a textual point of view, this ‘shallow’ representational narrative device remains successful, if only on a mythic romantic level. As in the hero's intertextual link with his previous film role in Romeo and Juliet, love conquers all, even death. James Cameron, the director, who will be discussed in detail later regarding the development of cyborgs in Terminator (1984) and other films, has succeeded in creating what appear at first sight to be mythic agents who can embody audiences’ fantasies, needs and fears for a new millennium, by indulging and legitimising a renewed form of nostalgia for nature. This overblown text, which comfortably fits into the natural disaster sub- genre, is not necessarily designed to be strong on praxis through the resolution of problems, yet can be read as provocative, as its narrative implications prompt a renewed symbiosis between ‘eco-sapiens’ and their environment.

At the outset, the most overt critique embedded in the text centres on class. But most critics agree that it presents a simplistic evocation of class politics, with its working classes more easily enjoying themselves yet trapped in the bowels of the ship, in contrast to their stuffy counterparts ‘upstairs’. Audiences are clearly positioned to identify with the jouissance of the lower orders, yet invited at the same time to wallow in the luxuriant pleasures and material benefits of the wealthy. Nevertheless, because ecological concepts are not as clear-cut as ideological power divisions like class, Titanic can at least question outmoded notions of rationality and affirm a more eco-centred consciousness.

By representing and establishing holistic if enigmatic ecological tropes, Titanic begins to extend a nascent thematic and aesthetic lexicon which often unconsciously expresses, even legitimises, core ecological precepts, especially ecologism which promotes the principle of sustainability. Titanic suggests humans have to be educated to consume less and to produce more self-sufficiently to satisfy their basic needs.

Nature and the Roots of Ecology

'Ecologism', argues Andrew Dobson, makes

the Earth as physical object the very foundation-stone of its intellectual edifice, arguing that its finitude is the basic reason why infinite population and economic growth are impossible and why consequently, profound changes to our social and political behaviour need to take place

(cited in Talshir 1998: 13).

Dobson reconstructs ecologism as a comprehensive ideology in which the philosophical basis (limits to growth), the ethical perspective (ecocentrism), the social vision (a sustainable society) and the political strategy (radical transformation, not reformism) provide a coherent and cohesive ideology (ibid.: 15). Ecologism most certainly validates the non-sustainability of resources together with its central premise of human interconnectivity with the rest of the biotic community and even with the cosmos. The abiding strength of these ‘holistic’ approaches is that they regard the interrelationship of environmental variables as a primary concern which is ‘explicitly anti-reductionist’ (Sklair 1994: 126). This holistic utopian, even spiritual, perspective will be illustrated in detail in subsequent chapters, most notably through a comparative study of The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) and Contact (1997).

But to begin this process of analysis, a working definition of ecological utopianism needs to be outlined by tracing its historical, cultural and theoretical antecedents. Particular emphasis will be placed on the divisions between ‘deep’ and ‘light’ (shallow) ecology which is also reflected in the tensions inherent in ideological critiques and the debates about utopianism to be explored later. Finally, before an evolving prototype for the textual analysis of film can be considered, a survey of philosophical/ political positions will also be used to illustrate critical positions emerging from ecology. In many ways, ecology has become the most dominant and inclusive discourse of the late twentieth century.

Most cultural critics generally begin with the premise that ‘our representation of nature’ usually reveals as much, if not more, abo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Fmt

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- FILMOGRAPHY

- 1. HOLLYWOOD UTOPIA: ECOLOGY AND CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CINEMA

- 2. NATURE FILM AND ECOLOGY

- 3. WESTERNS, LANDSCAPE AND ROAD MOVIES

- 4. CONSPIRACY THRILLERS AND SCIENCE FICTION: 1950s TO 1990s

- 5. POSTMODERNIST SCIENCE FICTION FILMS AND ECOLOGY

- CONCLUSION

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- GLOSSARY OF TERMS

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Hollywood Utopia by Patrick Brereton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.