![]()

1: Consciousness, Inspiration and the Creative Process

It is so well known as to be a truism that not everyone is good at everything: different people are good at different things. ‘Things’ can be arts, crafts, knowledge-based activities, or skills. As a result, people make use of what they are good at for various purposes: to gain enjoyment and satisfaction, and to earn their living. It is up for debate as to which of the two is more important to individuals themselves and / or to society. Some people ‘are good at’ writing plays. They are dramatists or playwrights. As with many other professions, occupations, or jobs, the outward measure of whether the playwright or dramatist is ‘good’ is the critical opinion of peers-fellow playwrights and those who read the plays and/or see them performed and comment on their reading or viewing experience. Such peer evaluation is either formal and public, or informal and private. Formal engagement with a playwright’s work can take the form of critical books and essays, or comments in interviews about a playwright, on the whole produced by academics or journalists. Discussions of plays (and that implies their writers) in class at school or university levels also come under this heading. Informally, spectators may discuss the performance of a play. Evaluation, furthermore, is either contemporary to the playwright in question, or may take place after his or her death. In a number of cases, playwrights received praise, were re-evaluated as ‘good’ only after their deaths, lacking recognition and related financial income during their lifetimes.

What motivates a playwright to write a play? To answer this question, let us first look at motivations and processes at work in various other occupations. In the case of some occupations, the impulse of what needs doing comes clearly, and only, from outside the individual following those occupations: a car mechanic is confronted with a specific type of car and a specific kind of task in relation to the car, such as, repairing faulty brakes. Acquired knowledge and skills, based on training and experience in the job, allow the mechanic to tackle the task in hand, and the level of skill determines the speed and efficiency of the repair. In other occupations, the impulse of what needs doing comes from a combination of factors both outside and inside the individuals following those occupations. Take the example of a car manufacturer. If management requests a new model to be developed, this represents an outside impulse to the colleagues involved in the design of the new model. The designers will have to combine existing knowledge of materials and their characteristics, processes, shapes, sizes, colours, etc. to produce something new. The process and the ability involved (and required!) here are referred to as creativity. Creativity is also an essential asset in many aspects of (business) administration and management.

Creativity research is a vast field, as documented, for example, by the Encyclopedia of Creativity (1999) and at least two specialist refereed journals, Creativity Research Journal and Journal of Creative Behavior, and there is an equally strong market in creativity enhancement programmes1. The playwright may function within the parameters set by those two scenarios (outer motivation and creativity): several fairly uncomplicated possibilities come to mind. A playwright who has already written several plays with more than one character may want to experiment with form and thus decide to try his/her hand at a one-person show. Thus British dramatist David Pownall said: ‘As a writing exercise it’s very very exciting and good for me. You have to entertain with just one person on the stage’ (Meyer-Dinkgräfe, 1985a). Some playwrights confirm that particularly writing one-person shows is motivated by commercial reasons: plays that require only one performer, together with a minimum requirement for design, are more flexible and easier to sell than a play with a large cast (Meyer-Dinkgräfe, 1985a, MacDonald, 1985, Gems, 1985, Drucker, 1985). One might be tempted to cite commercial reasons for a playwright’s interest in a type of play that appears to be commercially successful. Since the late seventies, for example, plays about artists have thrived in Britain, a trend triggered by the success of Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus and Piaf by Pam Gems. Some plays in the wake of those two trendsetters were clearly poor attempts of jumping the bandwagon. For instance, Cafe Puccini premiered in the West End in 1986, and failed mainly because the production expected actors to sing Puccini arias, accompanied by four strings, piano, flute and accordion. Trained opera tenors have their problems with Calaf’s aria Nessun Dorma from Puccini’s Turandot. If an actor with some voice training attempts to sing this aria live on stage, it is, according to one critic, a laudable act of bravery, ‘but no one should have done this to him or to us!’ (Colvin, 1986: 21). The show closed after only forty- three performances. After Aida is another example of a commercially intended but unsuccessful play, dealing with the last phase of Giuseppe Verdi’s career. It played for twenty-eight performances. Times critic Wardle wrote:

There is no dramatic situation. The setting [the stalls of a theatre] is merely a playground where speakers can address us with memoirs, team up for brief scenes and rehearsals (...) members retreat to the stalls to read newspapers or sit looking bored; a sight that leaves you wondering why you should be interested in a spectacle they cannot be bothered to look at (1986).

Superficial ‘outside’, commercial reasons, however, are not sufficient to explain all dramatic output. In the majority of cases, the processes involved in playwrighting (as with many other artistic activities) go beyond ‘outside’ motivation and even the kind of creativity described above as relevant to car design or management: playwrights claim an inner need to write a particular play. In those cases, creativity is closely linked with inspiration, defined by the Oxford English Reference Dictionary as ‘a supposed force or influence on poets, artists, musicians, etc., stimulating creative activity, exalted thought, etc.’ (1996)

Interviews with playwrights provide rich source material for a study of inspiration. On the basis of a several descriptions of inspiration by playwrights themselves, taken from a range of interviews, I will derive a number of general points of information about inspiration. I will place them in the context of attempts, over the centuries and in the Western tradition, at explaining inspiration. The chapter concludes with an alternative explanation developed within the context of Indian philosophy.

Examples of Inspiration among Playwrights

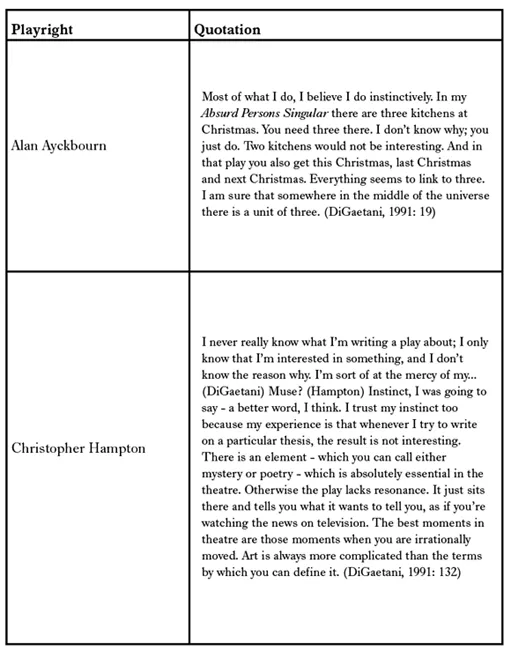

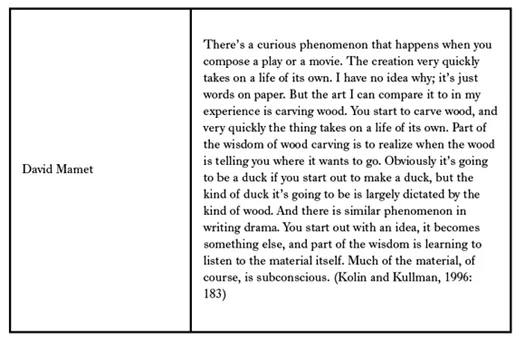

I want to begin this section with three almost randomly selected quotations.

These three statements share a few common characteristics: the dramatists in question don’t know why, don’t understand why, have no idea why they write as they do, they talk about instinct, inspiration, mystery and poety, and miracle. Let’s keep those shared characteristics of dramatic writing in mind and look more precisely at some dramatists who share writing about fellow artists.

David Pownall had read the minutes of the composers’ conference held by the communist party in 1948 in Moscow: ‘Those minutes froze your blood on the one hand, but they also made you laugh. There was a kind of mixture of horror and mockery (...) and I immediately knew that I wanted to write a play about this’ (Meyer-Dinkgräfe, 1985a). The result is Master Class, which shows a fictional meeting between Stalin, Shostakovich and Prokofiev in the Kremlin. Pownall’s intention in writing the play was to convey, if possible, the same feelings to the audience he had experienced while reading the minutes. While Tom Kempinski was working on Duet for One, he was suffering the first stages of agoraphobia. For him, the psychiatrist character in the play, Dr. Feldman, and the artist, Stephanie, represented the life-supporting and life-threatening forces within himself, in his struggle between survival and suicide (Glaap, 1984).

The examples of Pownall and Kempinski show that inspiration is again central to their creative acts, and it is very personal events in the lives of the dramatists that serve as inspirations to write a play about a fellow artist. Generally speaking, dramatists have to depend on their intuition, as Peter Shaffer puts it: ‘One is not finally aware of why one idea insisted or the others dropped away (...) The playwright hopes that one will say: ‘Write me! Write me!’’ (Buckley, 1975: 20). Many dramatists confirm that they had reached a stage in their artistic development at which they wanted to reflect about the nature of art and the implications of being an artist.

Having established some common patterns relating to the creative process characteristic of dramatists, I now want to compare those findings with reports by artists in other genres about their creative process.

Examples of Inspiration among other Artists

Not only playwrights have described what inspired them to write their plays. We have similar accounts also from representatives of other forms of art. All the cited artists are famous ones, those who have achieved greatness in their fields. This could at first sight be due to the fact that only because they are famous have their experiences been recorded and published. Moreover, however, current research suggests that high achievers in any field or occupation are likely to have more frequent instances of experiences such as inspiration, than less high achievers (Harung et al., 1996). Composer Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) described the creative process of his composing on the condition that the material be published only fifty years after his death. Inspiration for Brahms originates in a level of reality that is both real and apparently unmanifest:

It happens not only through the power of will, through conscious thinking, which is a product of development of the physical level and dies with the body. It can only happen through the inner forces of the soul, through the real I, which physically survives death. Those forces are dormant for conscious thought, unless they are illumined by spirit. (Volkamer, 1996: 26)

Later, Brahms adds:

Initially I know (...) that it is a real, lively force, the source of our knowledge. You cannot experience through conscious thought, which is the product of the realm of matter; it can be perceived only with the true, eternal Ego, the inner force of the soul (...) I always think about all this, before I start composing (...) Immediately afterwards I sense vibrations that permeate me through and through. They are the spirit that illumines the inner forces of the soul, and in this state of rapture I see clearly what is dark in my usual state of mind; then I feel able to allow myself to be inspired from above, like Beethoven. (...) These vibrations take the shape of specific mental images, after I have inwardly uttered my wish and decision of what I want, namely to be inspired to compose something that uplifts and supports humankind- something of lasting value. Immediately ideas come streaming towards me (...) Not only do I see specific themes in front of my mind’s eye, but also the appropriate form in which they are shaped, the harmonies and orchestration. Bar by bar the finished work is revealed to me. (Volkamer, 1996: 26-7)

Fellow composer Richard Wagner (1813-1883) reports:

While working (...) I had many wonderful and enlivening experiences in the invisible realm, which I can describe, at least to some extent. First of all I believe that this universal, vibrating force connects the human soul with that omnipotent central force, from which our life principle derives, to whom we all owe our existence. For us this force represents the link to the highest power in the cosmos, of which we are all a part. If it were not like that, we would not be able to connect with it. Those who are able to connect will get inspiration. (...) I sense that I am one with this vibrating force, that it is omniscient, and that I can create out of it to an extent that is limited only by my own ability. (Volkamer, 1996: 29)

Poet William Wordsworth (1770-1850) coined the now famous phrase ‘emotion recollected in tranquillity’ in the context of describing the creative process:

I have said that poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity: the emotion is contemplated till, by a species of reaction, the tranquillity gradually disappears, and an emotion, kindred to that which was before the subject of contemplation, is gradually produced, and does itself actually exist in the mind. In this mood successful composition generally begins, and in a mood similar to this it is carried on; but the emotion, of whatever kind, and in whatever degree, from various causes, is qualified by various pleasures, so that in describing any passions whatsoever, which are voluntarily described, the mind will, upon the whole, be in a state of enjoyment. (1969: 740)

Finally, Franz Kafka (1883-1924) wrote:

It is not necessary that you venture out of doors. Stay at your table and listen. Don’t even listen, just wait. Don’t even wait, be completely still and alone. The world will offer itself to you to be discovered, it cannot do otherwise. Enchanted it will writhe in front of you. (1988)

For further collections of such accounts, see Ghiselin (1952) or Shrady (1972).

Common Characteristics of Reported Inspiration

Looking across those, and many more reports of inspiration provided by artists across the genres, it is possible to extract a number of characteristics they all share.

• Many artists do not clearly know how they get their important creative ideas, and refer to inspiration or instinct if asked to explain;

• Inspiration is considered a blessing;

• Artists blessed with inspiration attribute the creation of their best work to inspiration;

• Specific procedures help Brahms to gain intentional access to a state of inspiration. Most artists, however, have to rely on coincidence;

• Inspiration is associated with a specific mental state that is different from the ordinary state of waking. It is within this state of being that the creative process takes its origin, the source from where it develops;

• This state is often located between waking and sleeping;

• Inspiration is very powerful and creates awe-hence its attribution to the divine.

Explanations of Creative Inspiration

Having established common characteristics reported by artists about their inspiration and about the processes involved in their creative activities, I now want to analyse attempts in Western history of ideas to explain, or make sense of, creative inspiration. From the beginnings of recorded histories of art in any form, inspiration, as described in the material above, has been part of the arts and the creative process. In Greek times, artistic inspiration was attributed to the Muses. They are goddesses, daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne (memory). Initially there were three Muses, later expanding to nine:

1. Calliope (Fair Voiced), epic poetry

2. Clio (Proclaimer), history

3. Erato (Lovely), love poetry and mimicry

4. Euterpe (Giver of Pleasure), music

5. Melpomene (Songstress), tragedy

6. Polyhymnia (She of Many Hymns), sacred poetry (sometimes also related to geometry, mime, meditation and agriculture)

7. Terpsichore (Whirler), dance

8. Thalia (Flourishing), comedy and playful and idyllic poetry

9. Urania (Heavenly), astronomy

The Muses preside over the art they are associated with, and, most important in our context, they provide the inspiration to the artists excelling in their art. The Greeks conceptualised the mind as having two chambers; one in which new thoughts occur, controlled by the gods. The gods, through the Muses, project their ideas by inspiring (literally: breathing into) one of those two chambers in human minds (Dacey, 1999: 310). From there, the material provided by t...