- 246 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This Collection of fourteen essays by eleven different authors demonstrates the increasing breadth of enquiry that has taken place in art and design education history over the past two decades, and the expanding range of research models applied to the subject. The essays are grouped into six sections that propose the emergence of genres of research in the field - Drawing from examples, Motives and rationales for public art and design education in Britain, Features of institutional art and design education, Towards art and design education as a profession, Pivotal figures in the history of art and design education, and British/European influence in art and design education abroad. The rich diversity of subject matter covered by the essays is contained broadly within the period 1800 to the middle decades of the twentieth century.

The book sets out to fill a gap in the current international literature on the subject by bringing together recent research on predominantly British art and design education and its influence abroad.

It will be of specific interest to all those involved in art, design, and art and design education, but will equally find an audience in the wider field of social history.

Contents include:

• Drawing from examples

• Motives and rationales for public art and design education in Britain

• Features of institutional art and design education

• Towards art education as a profession

• Pivotal figures in the history of art and design education

• British/European influence in art and design education abroad

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Histories of Art and Design Education by Mervyn Romans in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arte & Arte generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1: A Preliminary Survey of Drawing Manuals in Britain c.1825–1875

Rafael Cardoso

Among the many sources available for looking at nineteenth-century art and design education, drawing manuals stand out for their exceptional ability to uncover the many nameless procedures and discourses which only rarely filtered through to more formal expressions of theory and policy. Sifting through the great mass of ‘useful knowledge’ contained in the many hundreds of manuals published throughout the period, they can be found to contain a wealth of contemporary ideas not only on drawing instruction itself but also on art and education as broader social issues, often revealing hidden attitudes or barely articulated ones which, nonetheless, underpinned the nature of instruction at the time. Drawing manuals possess the further advantage of reflecting a wide and eclectic range of practices, often blurring or cutting across otherwise rigid barriers within nineteenth-century education demarcating divisions of age, gender, class or nationality. Despite their potential usefulness, however, surprisingly little has been published on the subject.1 The aim of the present article is to provide an initial survey of the historical development of drawing manuals during the critical 50-year period spanning the middle part of the nineteenth century, in the hope that this will encourage more extensive research in the field.

Until the 1830s, most treatises on drawing were directed almost exclusively towards well-to-do amateurs interested in sketching landscape and/or figure drawing, in pen and ink, sepia and watercolours. Like all illustrated books of the time, these tended to be fairly expensive items, a fact which necessarily limited their circulation. A series of technological developments throughout the first three decades of the century including the coming of the steam printing press and the increased use of wood pulp as a raw material for paper-making greatly reduced publishing costs, contributing significantly to the expansion of a new reading public among the middle and working classes.2 These segments of the editorial market were subsequently targeted with a barrage of elementary drawing manuals, a new cheaper range of manuals on landscape and, increasingly after 1850, manuals on technical subjects such as geometrical drawing, mechanical drawing and drawing for specific trades like carpentry or bricklaying. Manuals were often published in conjunction with the manufacture of artistic materials by companies such as Ackermann & Co., Reeves and Sons, Winsor and Newton or George Rowney and Co., the latter two coming to dominate the largely amateur market for one shilling manuals during the late nineteenth century. Publishing houses like John Weale’s, Chambers’s and Cassell’s were responsible for many of the technically oriented manuals, especially the cheaper ones, which found a ready market among the upper reaches of the working-class public. Prices for manuals during the Victorian period began at one penny or sixpence for very simple ‘drawing-copies’ and ranged as high as several pounds, with most resting in the one shilling to two shillings and sixpence range. Drawing books published in parts proved to be extremely popular, especially in the segment of elementary and technical manuals geared to artisans and mechanics, who might not be able to afford a single large outlay but were willing to invest smaller amounts over an extended period of time. A successful manual easily achieved four or five editions in as many years, and the most popular ones sometimes reached upwards of ten editions in a career spanning as many as 30 years or more in print. By the late 1840s and early 1850s, the supply of drawing manuals was already so great that one especially prolific author, Nathaniel Whittock, felt moved ‘to apologize for adding to the number’.3 Most of his fellow authors, however, saw the overwhelming demand for new editions as justification enough for writing even more manuals.

The impact of cheap engraving and printing was so immediate that the engineer and writer of manuals Robert Scott Burn described this contemporary revolution in mass communication as ‘more powerful than the press for printing words’.4 Independently of purely technological considerations, though, the expansion of the market for manuals cannot be dissociated from the broader drive to popularise instruction in art and design which served as a backdrop for the growth of educational and cultural institutions like those of South Kensington. The Department of Science and Art was itself a powerful agency for the dissemination of manuals – sold, issued and distributed under its authority by the publishers Chapman and Hall. Manuals often came recommended with the sanction of the Department, the Society of Arts, the Committee of Council on Education and other educational or charitable entities. Within a few decades, drawing ceased to be perceived as simply an ‘elegant art’ contributing to ‘a genteel education’ – as Whittock described it in 1830 – to become a necessary part of general education, for children of both sexes and all classes, as well as many working-class adults.5 An 1853 circular from the Committee of Council on Education reinforced this point, stating firmly that drawing ‘ought to no longer be regarded as an accomplishment only... but as an essential part of education’, and, by 1864, the Schools Inquiry Commission reported that 95 per cent of grammar and other publicly supported schools were teaching drawing to children, while 92 per cent of private schools were doing so.6 The speed and efficiency with which the new educational establishment succeeded in transforming drawing instruction into a standard commodity must be attributed, in no small degree, to the exceptional power of printed manuals and examples as tools for spreading visual knowledge.

With the initial expansion of the market between about 1825 and 1830, the comparative uniformity of manuals in terms of format and price gave way to more variegated and sophisticated publishing strategies. Whereas an older style of treatise like Dougall’s The Cabinet of the Arts (1815?) tried to encompass as many aspects of artistic practice as possible – claiming not only to teach drawing but also etching, engraving, perspective and even surveying – the newer manuals began to address particular media, topics of interest and stages of proficiency in a rather more specific manner. Some of the earliest books emphasising the possibility of learning elementary drawing without the aid of a master were published around this time, such as Thomas Smith’s The Art of Drawing in Its Various Branches or Whittock’s The Oxford Drawing Book, both dating from 1825.

Although both these books still bore a strong stylistic resemblance to the widely prevalent manuals of amateur sketching authored by noted landscape painters like David Cox, Samuel Prout or John Varley, they made an effort to adapt the tone and content of their lessons to a new audience which might possess neither previous experience of drawing nor ready access to private instruction. The latter book appealed quite unashamedly to the pretensions towards gentility of its eager middle-class public, couching the simplicity of its method in artfully Romantic assertions of the elegance of drawing as a pastime.

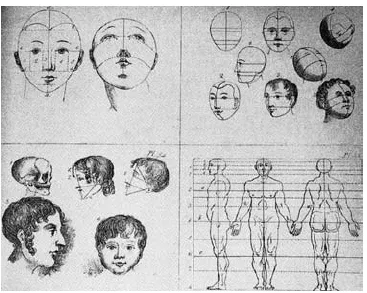

Fig. 1: Traditional examples of heads and figures from Whittock’s Oxford Drawing Book.

The 1820s also witnessed the initial publication of one of the earliest truly rudimentary drawing manuals for a mass public. Taking advantage of a format popular at that time for learning all sorts of subjects, Pinnock’s Catechism of Drawing first appeared around 1821, running into at least two subsequent editions in the 1830s, and followed by Robert Mudie’s A Catechism of Perspective in 1831. Although the question and answer structure of the catechism left little room for anything substantial in the way of visual instruction, the fact that drawing was considered to be a form of knowledge worthy of inclusion in a popular educational series even at this early date is significant. One final manual worth mentioning in the context of the 1820s is Louis Benjamin Francoeur’s Lineal Drawing, and Introduction to Geometry, as Taught in the Lancastrian Schools of France (1824), the first of two English-language translations of Le Dessin Linéaire (1819). Francoeur was the author of treatises on mathematics and mechanics, and this simple manual was intended for elementary instruction using the monitorial system.

Nonetheless, the book broke new ground in two ways: firstly, it was specifically directed towards the ‘middling and lower classes of society’ and, secondly, it attempted to address geometrical drawing as a subject in its own right, apart from the artistic aspects of the study.7 The tendency thus inaugurated of directing working-class practitioners to a particular kind of low-level, technical drawing is certainly of grave import, but it is a subject too large and complex for the scope of the present discussion.8

Despite these early examples, both the number and variety of drawing manuals published in the 1820s and 1830s were still comparatively small. A few truly technical manuals appeared occasionally during the 1830s, like Thomas Sopwith’s A Treatise on Isometrical Drawing (1834) or Blunt’s Civil Engineer and Practical Machinist by Charles John Blunt, but these tended to be expensive volumes, directed to very restricted professional groupings like geologists and civil engineers. Growing public and political agitation over education during the 1830s contributed to changing all that, however. The formation of the Committee of Council on Education provided an important incentive by creating an authority interested in bringing out standard classroom texts, particularly in terms of drawing instruction which had not heretofore been perceived to be an integral part of education by any of the sectarian publishing societies. One of the first drawing manuals published under the sanction of the Committee of Council was C. E. Butler Williams’s A Manual for Teaching Model Drawing from Solid Forms (1843). Butler Williams was a key figure in the history of popular drawing instruction, being among the first to teach drawing on a large-scale basis in his classes at Exeter Hall. His system of teaching drawing from three-dimensional models was based on that of Dupuis, in France, and constituted something of a landmark in the struggle against the widely prevalent practice of copying from the flat, which he dismissed as mere rote-work.9

The book was a great success and contributed to the popularity of methods that employed simple models made of wood or wire in learning to draw basic geometrical shapes. Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins’s The Science of Drawing Simplified was published that very same year, sold complete with a set of models and a portable cabinet box for a rather pricey £2.2s. Other systems of model drawing continued to be very popular throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century.

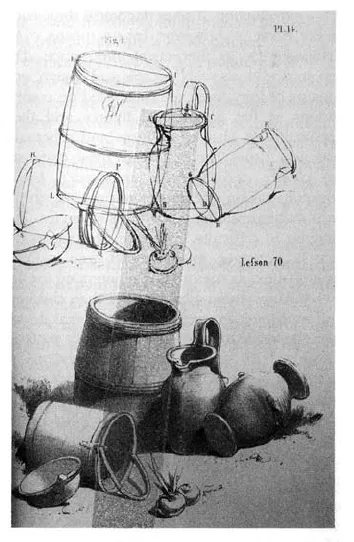

Probably the greatest editorial success among drawing manuals of the 1840s was J. D. Harding’s Lessons on Art (1849). Although the first edition was priced well above the reach of even some middle-class learners, at 21 shillings, the book proved to be enormously popular and went into ten editions over the following three decades. Harding, of course, is better known as a landscape painter; yet his influence as a drawing master was enormous by any standard. Lessons on Art typifies the ‘progressive method’ which became almost standard in the elementary manuals of the latter half of the nineteenth century. The first lessons begin with the freehand drawing of straight lines, angles and rectilinear shapes, moving from there to curves and solid geometrical shapes. The second section of the book involves applying these abstract shapes to simple objects and buildings: drawing a fence from intersecting parallel lines or a bridge from an arc. The third section then moves back to circumscribing solid objects with abstract geometrical shapes, as a simplified means of introducing perspective drawing. More complex objects, largerscale buildings and whole landscape scenes follow in subsequent sections. The system relies on creating a dynamic tension between abstract shapes and real objects, thus establishing an easy and logical transition from representing twodimensional surfaces to three-dimensional space. Harding’s methods were widely copied by other elementary manuals of the period, but rarely with the same success.

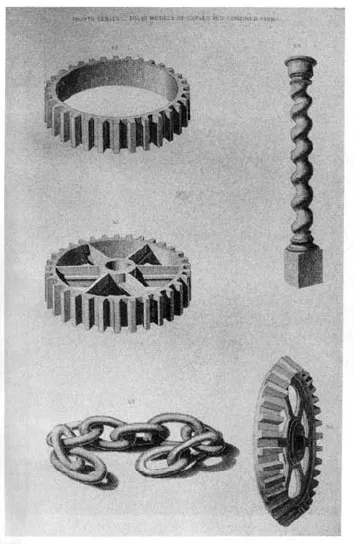

Fig. 2: Solid models used in Butler William’s method.

Fig. 3: Harding’s method of using auxiliary lines to discover geometric shapes in objects.

The fact that many elementary manuals employed very similar approaches to drawing is no coincidence, since they were often directed to a fairly homogeneous segment of the public: namely, children and youths of the middle classes, as well as the drawing masters who taught them. Of course, there were those who could not afford drawing masters, and accordingly, self-instruction became an important aspect of the compilation of manuals, many of which emphasised their effectiveness in learning without a master or even as aids for schoolteachers who did not themselves know how to draw. As opposed to supervised work, however, self-instruction posed the risk of students deviating from approved methods and examples. In order to minimise this danger, most manuals stressed the importance of close adherence to the prescribed instructions. In fact, the preoccupation with surveillance was so strong that some authors took the trouble to detail the finer points of how students should sit, hold their chalk, clean their slates or sharpen their pencils. Butler Williams’s manual was an extreme example of this disciplinarian attitude, including fourteen pages of minutely itemised directions regarding nearly every aspect of classroom practice.10

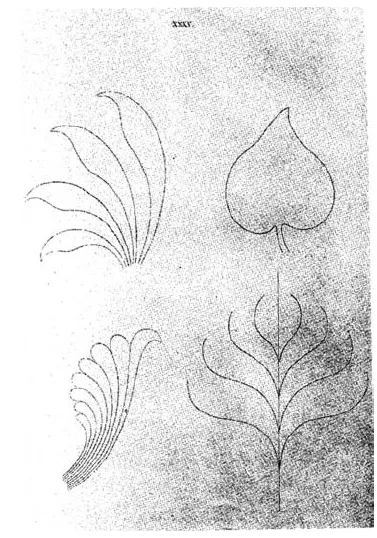

Fig. 4: Some of Dyce’s ‘tracings’.

Another exceptional manual produced in the 1840s was William Dyce’s The Drawing Book of the Government School of Design; or, Elementary Outlines of Ornament, which was initially printed for the use of students at Somerset House in 1842–3 but was not made generally available until 1854. Dyce’s manual offered a radical departure from previous methods of drawing instruction, not only in the way its exercises were organised but also in the complex theoretical discussion of the nature of design and ornament which constitutes much of its introduction. The pedagogical dimension of the book is, however, by no means overshadowed by its theoretical importance. The first section deals with ‘geometrical design’ and consists of 45 exercises based on combinations of flat geometrical figures and their application to abstract patterns and schematic botanical forms. The first ten of these exercises are clearly derived from Francoeur’s Lineal Drawing, taking students from drawing simple lines to circumsc...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Notes on Authors

- Introduction: Rethinking Art and Design Education Histories

- Chapter 1: A Preliminary Survey of Drawing Manuals in Britain c.1825–1875

- Chapter 2: ‘How to Draw’ Books as Sources for Understanding Art Education of the Nineteenth Century

- Chapter 3: A Question of ‘Taste’: Re-examining the Rationale for the Introduction of Public Art and Design Education to Britain in the Early Nineteenth Century

- Chapter 4: Social Class and the Origin of Public Art and Design Education in Britain: In Search of a Target Group

- Chapter 5: Birmingham and its Art School: Changing Views 1800–1921

- Chapter 6: Women and Art Education at Birmingham’s Art Schools 1880–1920: Social Class, Opportunity and Aspiration

- Chapter 7: The Early History of the NSEAD: the Society of Art Masters (1888–1909) and the National Society of Art Masters (1909–1944)

- Chapter 8: InSEA: Past, Present and Future

- Chapter 9: Looking, Drawing and Learning with John Ruskin at the Working Men’s College

- Chapter 10: Marion Richardson (1892–1946)

- Chapter 11: Herbert Read: a Critical Appreciation at the Centenary of his Birth

- Chapter 12: Basic Design and the Pedagogy of Richard Hamilton

- Chapter 13: Who is to do this Great Work for Canada? South Kensington in Ontario

- Chapter 14: European Modernist Art into Japanese School Art: the Free Drawing Movement in the 1920s

- Index