eBook - ePub

A Devon House

The Story of Poltimore

Jocelyn Hemming

This is a test

Share book

- 115 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Devon House

The Story of Poltimore

Jocelyn Hemming

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A DEVON HOUSE relates the story of one of Devon's great houses through the people and events which have coloured its existence over the past 400 years. The book traces the architectural progression of Poltimore from Tudor manor to grand 20th century mansion, records its historic role in England's tempestuous Civil War and details its use after 1920 as first a school and then a hospital. It will appeal to all those who knew the house and estate in a personal capacity in the past, those who have visited it since the formation of Poltimore House Trust in 2000 and the Friends of Poltimore House in 2003, and those interested in the conservation and regeneration of historic buildings.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is A Devon House an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access A Devon House by Jocelyn Hemming in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Detail from Rococo plasterwork in the Saloon. Photograph Dick Brownridge

The Bampfylde Builders: from the 17th to the 20th Century

Coplestone Bampfylde, 2nd Baronet (1636–91) carried out an extensive modernisation of his father’s Tudor house during the period 1680–90. Although the layout remained more or less the same, the original winding stair in the tower was replaced by a new oak staircase, typically late-17th-century with square newel posts, turned pendants and finials and turned balusters with a flat, moulded handrail. The windows were probably altered at the same time, all this work being consistent with the date of 1681 of the ‘Bowls’ on the gate piers marking the entrance to the estate from the Broadclyst road. At one time it was thought that Coplestone was also responsible for the richly decorated Saloon, formerly the hall of the house where the Treaty of Exeter had been signed in 1646, and that it had been designed in honour of the future Queen Anne who, tradition says, may have visited Poltimore during her tour of the South West after the Restoration. The decoration includes plaster heads said to be of George, Prince of Denmark, Anne’s consort, and of their only child to survive infancy, William, Duke of Gloucester, identified by his abnormally large head (he died of hydrocephalus in 1700). However, this would date the fine plasterwork to the end of the 17th century, whereas rococo work of this quality was not known in the South West for at least another thirty or forty years. Sir Coplestone Bampfylde died in 1691 at about the same time as his son Hugh, leaving a two-year-old heir to the baronetcy—his grandson, Coplestone Warwick Bampfylde.

It might seem, therefore, that the second Sir Coplestone (1689–1727) was the architect of this major embellishment; however, in view of his somewhat short life it seems more likely to have been his son Richard Warwick Bampfylde, 4th Baronet. (The confusion between the two Coplestone Bampfyldes, 2nd and 3rd Baronets, whose lives both spanned the last years of the 17th century is understandable, and is confounded by the fact that Coplestone Warwick Bampfylde’s brother, John

Gertrude Carew, wife of Sir Coplestone Bampfylde. Photograph Dick Brownridge

Bampfylde, named his son by Margaret Warre of Hestercombe in Somerset, Coplestone Warre Bampfylde. It was Coplestone Warre Bampfylde, an artist, who created the Secret Garden at Hestercombe, near Taunton, which was rediscovered and restored in the 1990s. Nevertheless, the royal connection with Poltimore House is enhanced by the fact that Queen Anne presented Coplestone Warwick Bampfylde with a portrait of herself by Sir Godfrey Kneller which, however, could not have been painted until after her accession in 1702 as it shows the Queen in state robes with orb and sceptre. This painting hung in the house, although probably not in the Saloon, until the sale of the contents in 1923; its whereabouts is not now known, although a copy is believed to exist in Washington DC. A three-quarter-length portrait of Coplestone Warwick Bampfylde, by an unknown artist, shows him wearing a full-skirted coat of apricot-coloured velvet and lace cravat, standing with hand on hip, a pose typical of the period. His wife, Gertrude Carew, in steel-blue satin, provides a complementary painting of the same size; both can be seen at Hartland Abbey in North Devon.

Whoever its creator, the exuberantly decorated and gilded 18th-century Saloon has been described as ‘one of the finest rooms of its kind in the county’ by Cherry and Pevsner. Poltimore could not, of course, rival in magnificence the great houses of the mid-18th century such as those Palladian masterpieces Chiswick House or Holkham Hall in Norfolk, and no doubt was not intended to. Nevertheless, the cornice in the Saloon is classical in design, the outer walls draped with swags of fruit, foliage and flowers in plaster with oval mirrors in carved and gilded lime wood frames. The chimneypiece was rebuilt in the centre of the inner wall with a fire surround in white- veined marble with massive ormolu-gilt swags of fruit, steel grate and mantelpiece of painted wood and carved with a hound’s head and hunting horns and hounds’ tails on either side. Over the chimneypiece there was once a carved frame with broken pediment containing a small statuary group, the frame surrounding an oil painting of the coast of North Devon or Cornwall. Above the mahogany doors at the ends of the room are lion masks with elaborate swags of fruit and flowers and on either side of the doors, tall alcoves, which until 1920 contained statues of biblical subjects, one of St John as a child and the other the Son of the Shunamite (the subject of one of the Prophet Elisha’s miracles, 2 Kings, 4.xii). The plaster ceiling features what is thought to be the head of Queen Anne (although Apollo has also been suggested as a subject) surrounded by floating clouds with sunrays radiating outwards through a laurel wreath towards two pairs of storks, the rest of the ceiling ornamented with swirling ropes and seaweed ending in shells at the four corners. When newly finished and lit by many candles the whole effect must have been extraordinary.

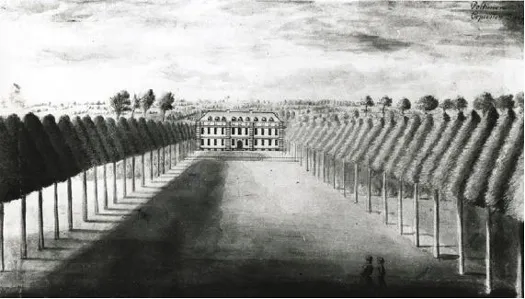

The south front in 1727 as drawn by Edmund Prideaux for Sir Coplestone Warwick Bampfylde

If the second Sir Coplestone was not responsible for this splendid creation he certainly carried out other transformations. He constructed the courtyard plan and the south front, as seen in Edmund Prideaux’s drawing of 1727 with Sir Coplestone’s name inscribed. It should be mentioned that Edmund Prideaux made only two journeys to the South West of England, in 1716 and 1727. His one drawing of 1716, made for the 3rd Baronet, shows the Tudor north range of Poltimore House and in front of it a wide canal flanked by clipped trees and grassy rides, leading straight to the house and dividing to form branches on either side of the house. This appears to be a canal after the style of the Hampton Court water courses made fashionable in the mid-17th century, here a landscape feature as well as a fishpond, witness the two figures fishing in the left-hand corner of the drawing. Future archaeological investigations might throw light on the existence of such a watercourse. The fact that it was drawn in 1716 does not preclude the possibility that the canal had been introduced by the first Sir Coplestone in the mid-17th century.

Sir Coplestone Warwick Bampfylde, however, undoubtedly redesigned the gardens on the north front during the eleven years between 1716 and 1727. When Edmund Prideaux again visited Poltimore in 1727 he drew a different view of the north front, this time ascribed to Sir Richard Bampfylde, the 3rd baronet’s son who must only just have inherited the estate in that year. The canal had been filled in and a garden laid out with serpentine paths, statues and topiary— occupying approximately the lawned area on the east side of the house today. Sir Coplestone certainly had money to spend, for by 1727 the entirely new south range of Poltimore House had been built, viewed at the end of an avenue of trees and complete with grand symmetrical eleven-bay front, central entrance and dormer windows alternately rounded and pointed, in the roof. The deer park was probably enlarged at this stage and the forecourt in front of the house fenced off.

The new south front contrasts vividly with the Elizabethan north elevation of the house. Prideaux’s drawing shows that it was symmetrical about the central doorway which is contained in a discreetly projecting bay three windows wide, flanked on either side by equal lengths of wall each containing four windows on each storey. The house is now plastered externally with its only decoration being banded pilasters flanking the central bay and at each corner. Instead of presenting a row of gables, the roof is tucked behind a panelled parapet. The whole effect is one of restraint, something that is not generally characteristic of this period of architecture in England when grand buildings were often built with a lavish use of classical motifs. Indeed it gives the appearance much more of a French mansion of this period than of an English one, and one wonders if Sir Coplestone Bampfylde, if he had not actually been to France, for which there is no evidence, might have visited and been influenced by houses in England designed in a French style or by French architects, such as Petworth house in Sussex c.1686 or Dyrham Park in Gloucestershire c.1692.

A century later Ackermann’s print of 1827, the fourth of the images of Poltimore House known to exist before photography, is of the stuccoed south-east front with fallow deer (Cervus dama), a species of European origin, free to graze right up to the house, a practice which continued until 1939. Saxton’s map of Devonshire engraved in 1575 shows Poltimore as a deer park, probably spread over many acres where the deer would have been hunted. By the 18th century, when deer were considered as much ornament as quarry, the enclosure would have been brought to the vicinity of the house, and the herd, when necessary, culled for venison. In the late 19th century, when the park was enlarged, the fallow-deer herd was augmented by Japanese Sika deer (Cervus nippon), a smaller breed with attractively marked heads. In the 20th century Lord Poltimore also kept black Welsh Mountain sheep in the park, the descendants of which are today at Hartland Abbey in North Devon.

The south front of Poltimore House in 1827

During the hundred years from the middle of the 18th century the Bampfyldes, having greatly embellished their grand house, became involved in politics, and the 3rd, 4th and 5th Baronets successively sat as first Tory and then Whig MPs for Exeter or Devon. No carpet-baggers moving around the country pocketing boroughs, they lived in their constituencies either at Poltimore House or in Exeter at Bampfylde House. The most enthusiastic of the Poltimore politicians was Sir Charles Warwick Bampfylde, 5th Baronet, who was elected to represent Exeter eight times between 1774 and 1807. In 1776, the year he succeeded to the baronetcy, he married Catherine Moore (1754– 1832), whose full-length portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds, himself a Devonian, hung in Poltimore House until after 1885 and is now in the Tate. It is a striking example of portraiture of that period, indicating the influence of the great Dutch masters on Reynolds’s style. Lady Bampfylde is painted in a baroque landscape, which could easily be part of Poltimore’s wooded grounds before the 19th-century pinetum was made, and it is not difficult to imagine her entertaining her husband’s political cronies in Poltimore’s white and gold Saloon. Music was surely also performed in this fine room; from the 1740s onwards the Bampfyldes are recorded as subscribers to new musical compositions (cantatas, anthems and sonatas), Catherine Bampfylde in 1784 contributing to Edward Jones’s Musical and Poetical Relicks of the Welsh Bards. Thomas Hudson’s painting of the same Catherine Bampfylde, in many ways a more arresting portrait, is now at Hartland Abbey in North Devon. She is without the powdered headdress of the Reynolds portrait, dressed in pale satin, unadorned, with a posy in one hand.

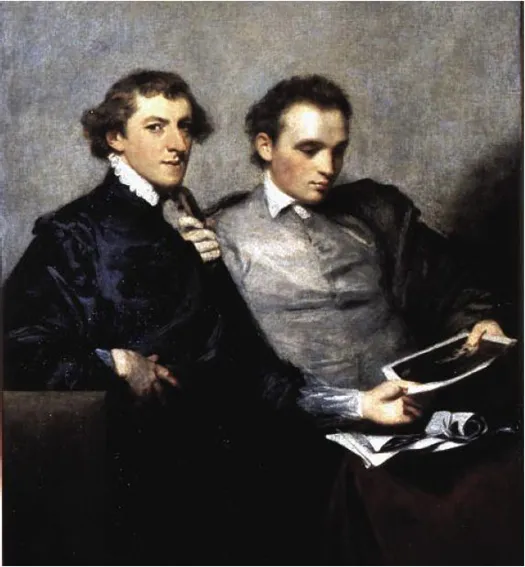

In 1779 Reynolds also painted the 5th Baronet’s brother, John Codrington Warwick Bampfylde, in a double portrait, also in the Tate, with his friend George Huddesford. The two young men could not have been more different in both appearance and character. Huddesford the elegant wit and satirist who later became a cleric, regards the artist with a sideways glance and a hint of a smile; Bampfylde, an aspiring poet and musician, serious-faced, less confident, casually and romantically dressed and holding some sort of musical instrument, accepting a printed paper from his friend. Bampfylde lived modestly at Catshole on the River Teign near Chudleigh, making occasional forays to Exeter where he is said to have played on the Cathedral organ. The organist William Jackson (1730-1803) an Exeter musician of merit, was also a popular composer of ballads, many of which were set to lines written by John Bampfylde. Another admirer of Bampfylde was the poet Robert Southey who may well have been the observer of his poor young contemporary as being ‘craz’d with care or ‘coss’d in hapless love’, a state of affairs which continued until 1778 when, on arrival in London he fell in love with Reynolds’s niece, Mary Palmer. This affection was either not reciprocated, or else it was stopped from getting anywhere by Sir Joshua himself. John Bampfylde dedicated his Sixteen Sonnets to his love and, when he was rejected, wrote his ‘Stanzas to a Lady’ expressing his despair:

Catherine Moore, wife of Sir Charles Bampfylde, painted in 1776 by Sir Joshua Reynolds. Reproduced by courtesy of Tate, ©Tate, London 2005

‘In vain from clime to clime I stray

To chase thy beauteous form away,

And banish every care;

In vain to quit thy charms I try

Since every thought creates a sigh,

And every wish a tear.’

To chase thy beauteous form away,

And banish every care;

In vain to quit thy charms I try

Since every thought creates a sigh,

And every wish a tear.’

George Huddesford (L) and John Codrington Bampfylde. A double portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1779. ©Tate, London, 2005

Reynolds had Bampfylde more or less thrown out of his house in Leicester Fields, St Martins-in-the-Fields (presumably after completing the double portrait), and as a result Bampfylde, leaving in a fit of rage, broke some of the windows. For this he was arrested and fined £20—paid by his friends Huddesford and Joseph Millidge, the publisher of his verses. After this episode he became insane and died of consumption in about 1796. Much of Bampfylde’s poetry is at times almost Tennysonian in its melancholy—the despair, the dripping eaves and lost hopes, as these lines from...