This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 362 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

About this book

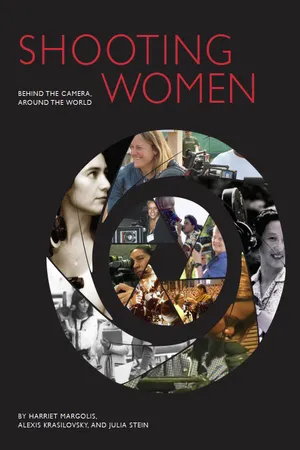

Shooting Women takes readers around the world to explore the lives of camerawomen working in features, TV news, and documentaries. From pioneers like African American camerawoman Jessie Maple Patton who got her job only after suing the union – to China's first camerawomen – who travelled with Mao – to rural India where women in poverty have learned camerawork as a means of empowerment, Shooting Women reveals a world of women working with courage and skill in what has long been seen as a male field.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Shooting Women by Harriet Margolis,Alexis Krasilovsky,Julia Stein in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Women in History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Cinematography is an elegant and desirable profession; it’s a real struggle to get into it. It is more difficult for women, because we’re a small percentage out there, and most of the crews we work with are male crews. So women have to empower themselves so they can be leaders, run a set, and work with men collectively. I don’t think women get that from an early age.

(Zoe Dirse)

Learning on the Job

Today, almost anyone who can beg, borrow, buy, or steal a camera can learn how to operate it up to a point, given sufficient determination, with or without formal training. “The lower cost of high quality camera choices has made cameras, videos, and photography a huge part of our lives,” Jendra Jarnagin observes, “and a major component of how everyone communicates, whether they are a professional or not.” It has also made it easier for people to teach themselves how to use a camera.

You can experiment and immediately see the results and learn from your failures. I grew up shooting film; it was expensive to experiment, so the learning curve was much slower. Now you can just mess around with your frame rates and shutter speeds and play it back on the spot and adjust accordingly. It can make for more bold techniques because you aren’t afraid of failure.

How does one become a professional? There were obviously no film schools in the 1890s when public screenings of films began around the world. Early equipment was simple; learning the basics wasn’t an obstacle, yet women rarely operated the camera in cinema’s early decades. Among the exceptions, though, are Margery Ordway, who worked in 1916 as a “regular, professional, licensed, union crank-turner” for the Hollywood feature Her Father’s Son (William Desmond Taylor); its DP, Howard Scott, was a founding member of the Society of Cinematographers (“This is the New Fall Style”). Elsewhere during the 1920s Louise Lowell was also claimed as “the first and only camera-maid in the world”; she studied aviation and became an aerial camerawoman for Fox Movietone News (“The First Camera-Maid”).

Around the world, most camerapeople learned on the job until relatively recently. Academy Award-winner Haskell Wexler, ASC, didn’t go to film school, but having a little mentoring made a big difference professionally. Wexler had shot 16mm family movies: “Not only shot them, but cut them, and put titles on them and all that stuff.” When he first started shooting, he learned by trial and error, and began shooting film for pay around 1947. Working professionally as an assistant in Chicago, Wexler was offered a job to shoot with a Mitchell Camera.

Figure 2: Louise Lowell, Fox News.

They asked me, “Can you shoot with a Mitchell?” I said, “Yes.” “Do you know macro photography?” I said, “Of course.” So I went to the library and read up on what macro photography meant. Val O’Malley, who worked at Wilding Studios, said, “I’ll help you. This is how you thread a Mitchell, a standard Mitchell.” He spent a couple of hours with me, and I got the job. I’ll never forget Val O’Malley.

Wexler has mentored many camerawomen, offering technical information, providing hours of work so women could join the union, and championing the cause of camerawomen generally.

Many women have learned on the job from male mentors. Lisa Rinzler says that after New York University (NYU) she worked briefly as a production assistant, immediately shifting to electric work and then camera assisting. She had a wonderful, unofficial mentor named Fred Murphy, who was a “terrific DP” and “a beautiful human being.” He taught Rinzler how to work under the pressures of a set. “I don’t think I light the way Fred lights, but on my first job he had me diagram his lighting for a movie he was shooting. I think I was working for free. None of that mattered: it was a fantastic opportunity to do drawings of someone’s lighting style. I was completely fascinated.”

American Madelyn Most trained at the London Film School and by working alongside Oscar-winning cinematographer John Alcott, BSC, who was DP on Stanley Kubrick’s films. Most said that if she asked Alcott a question, he would explain in detail for hours until she understood.

I was nurtured by people who worked for the film, and making you a better person and teaching you. I wanted to be like that, always teaching people, always discussing photography, discussing the problems, the labs. It’s not only knowing what you’re doing on the floor; it’s what they’re doing in the lab.

Similarly, Spanish camerawoman Teresa Medina, AEC, had a “beautiful” internship with Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC, while she was finishing her studies at the American Film Institute (AFI) and he was finishing Sliver (Philip Noyce; 1993). “Anything I wanted to say, anything I wanted to ask, he was always willing to help me. I will thank him for the rest of my life.” Among other things, Zsigmond taught Medina to respect the location for the shoot.

When we were working together, even within a studio where everything seems so artificial, I remember there being some translights, 1 and he told the gaffer he wanted to bring that same type of light into the décor of the set. He always respected his surroundings.

Medina also learned from her internship with Vittorio Storaro, ASC. One of the first female directors of photography to shoot a thesis film while at AFI, Medina was interested in technology: “How do you do this? How do you do that?” Storaro taught her, in addition, to trust in herself and to trust her intuition: “I learned to have an idea and to bring it to life. They are two different techniques: One wants you to respect the environment; the other wants you to bring something from within to the outer world. I use both.”

In Japan, Akiko Ashizawa, JSC, whose male mentor was Ito Hideo, recalls that

I wasn’t involved in cinematography before college. I had a hard time getting a job, except eventually at an independent production company that made “pink films” with nudity as their selling point. I found it a gathering of ambitious souls. One of them was Ito Hideo. He let me work as his apprentice assistant. The apprentice system helped me learn a variety of techniques. My training was never school-based.

Until recently, Kiwi camerawomen had few opportunities for formal camera training, so they learned on the job. In the 1970s Margaret Moth studied at Canterbury University in the fine arts class but switched to the new film class. She also learned on the job in a nation used to apprenticeships and on-the-job training for anything practical. She remembered that when “they were splitting the main [television] channel to be two channels, they were looking for camerapeople—well, cameramen. I had a big fight to get that job.” She got it, first learning to shoot black and white film, and within a few months she had learned to film color. Decades later, compatriot Kylie Plunkett’s experience has been similar. Despite a university degree and film school training, Plunkett says, “All camera training comes from real experience, on the job. Every job is different, so learning is every day. Technology is also changing so quickly.” Mairi Gunn’s experience in New Zealand also exemplifies what “coming up the ranks” from the bottom rung means for camera crews. She didn’t go to film school but did take a short weekend course in London with a Bolex (the classic wind-up 16mm camera). She got her first unpaid job as trainee on a short film and then slowly got more work as a camera loader and as a focus puller. Now she shoots her own films as well as working for others.

Some Canadian women had a different experience than those in the United States or Europe, since Canada has a government-sponsored National Film Board (NFB). Zoe Dirse, CSC, was fortunate to go to the NFB. Once hired, she could feel sure she wouldn’t be let go and she would shoot “six to seven films a year, which is a terrific training ground. Because there were editors, a lab, twenty other cinematographers you could talk to who had tremendous amounts of experience—the learning curve was high. I had a unique position as a woman.” Because the opportunity she had no longer exists, Dirse thinks women now have a more difficult time. She explains how to become a DP in IATSE (International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, a major union for film technicians): “You have to go through all the steps of training: second assistant, first assistant, operating, and then DPing. The difficulty lies in making that big step from camera assisting to operating, and then that bigger step from operating to DPing.” Dirse willingly mentors young camerawomen through the ropes.

Many countries do not have film schools, while universities around the world were slow to include film production in their curricula. The first university film courses were usually in appreciation, history, and other variations on humanities courses in the arts rather than in the practical skills needed to make a film. Where practical skills courses were offered, they generally were associated with programs in the practical arts such as painting or sculpture, architecture, and design.

Exposure to film studies in the humanities section of a university often leaves a would-be filmmaker in the position of having to teach herself how to operate the camera. Turkish filmmaker Berke Baş recounts that during graduate studies at New York’s New School she took “some camera editing classes, but there were no serious cinematography courses. There was no opportunity for us to hire a cameraperson. In order to make films, we had to shoot our own film. Digital technology helped us to get into the profession.”

A university education can be useful for a camerawoman apart from learning specific technical skills that may or may not be offered. For example, Dirse’s psychology professor at the University of Toronto taught his students about his research on “nonverbal behavior and facial expressions—which came in handy when I became a professional cinematographer, especially in documentary and working with people of other languages.” At the NFB, based in Montreal, a lot of the work was in French, but she was not then proficient in the language. Her first big documentary, Firewords (Dorothy Todd Hénaut; 1986), is about three feminist French Québécoise writers. Dirse applied her psychology professor’s ideas because “I had to rely on their facial expressions in terms of when to zoom in or change my frame, especially in the interviews.”

In fact, being at a university can provide relevant opportunities in unexpected ways. For a while in the 1970s, when cable companies were getting established in the United States, they often had to negotiate with local city councils for access to public utilities, leading to the establishment of public access cable television stations. Such stations, apart from the larger cities, were often located in college towns. Lisa Seidenberg’s discovery of public access video changed her life. After she received her degree in film and television from the University of Wisconsin, she returned home to Syracuse, New York (home of Syracuse University), and joined a video artist access program. She worked with pioneer video artists such as Nam June Paik and Carolee Schneemann, who were exhibiting at Syracuse’s Everson Museum. This early exposure to video—which was then new technology—gave Seidenberg practical skills with the equipment that virtually guaranteed her an industry job and the status of pioneer. A generation later, Jendra Jarnagin “began shooting at the age of twelve as a member of a public access youth program” (“About”); she has become an expert user and promoter of new camera technology.

Having any other women employees around can make a camerawoman’s life a little easier. In the mid-1970s NBC would have gaffers and camera operators come in to “day play” the news, i.e., work on a day-to-day basis rather than on permanent contract. That’s when Sandi Sissel, ASC, met Alicia Weber, who had a few months’ more experience and could mentor her. “I didn’t know much, so to have someone like Alicia—and there was a soundwoman named Nan Seiderman and another one named Cabell Smith—to have these women in the networks made it so much easier to function in that environment.”

First day at NBC, they check you out a camera. In those days it was a Frezzolini camera with two lenses and then your tripod. You would go all over New York. The DP drove the car; you carried your equipment, climbed stairs, and did whatever story they told you to do. It took me two weeks to realize that that additional lens was actually a wide-angle lens. I thought it was a spare lens.

Mary Gonzales described how Brianne Murphy, ASC, mentored her, taking her out of low-budget features and bringing her into network television. Murphy had worked as a cinematographer at NBC, Warner, and Columbia, becoming the first woman director of photography in Hollywood Camera Local IA 659. Gonzales said that Murphy nurtured many camerawomen and was the single most important person in her career, teaching her what she needed to know “technically, politically, emotionally.” Gonzales, who started working with Murphy on a freebie, was shocked that Murphy, who had years of experience, could still be doing a freebie. Gonzales was the second assistant camera on a two-camera Panavision film the first time she ever worked with professional cameras or professional crews.

We had a great time, and at the end of the production, [Murphy] gave us a gift: “Here’s a light meter. Learn how to use it.” And we did. Not that long afterwards she had me shooting Second Unit on a TV series called Shades of L.A. She’d just quietly tell the producer/director, “Send Mary out to shoot these exteriors.” Until she retired, I was pretty much her assistant and eventually B operator.

She and Murphy also became very good friends.

For Jo Carson, Estelle Kirsh was the mentor when Carson was first trying to get into live action camera work. Kirsh got Carson a job on a low-bucks or no-bucks movie: “It was a lot of fun, everybody was enthusiastic about it, we had a big crew.” Kirsh taught Carson “how we start in the camera world, from the bottom up. She taught me how to be a loader and how to do that right, and how to keep track of the records, load the magazines, keep everything shipshape. She did a good job of it. She knew what she was doing.”

Figure 3: Mary Gonzales, camera operator. USA.

Canadian Naomi Wise’s praise for Dirse is equally enthusiastic: If Wise hadn’t met Dirse, she wouldn’t have gotten trained—plus Dirse taught her “things the guys would never tell me.” For example, Dirse taught Wise that if male crewmembers asked her to pick up a heavy case she should “tell them to pick it up first. Because more than likely, they can’t pick it up either, and it’s a two-man job.” Thus Dirse taught Wise not only technical information such as how to change the film magazine but also “how to deal with the politics of the set.”

Around the world, as we shall see, camerawomen have stories of family influences leading them into camera work. Some have informally apprenticed themselves to family members.

For African American camerawoman and director Jessie Maple Patton it was her husband, LeRoy Patton, a cameraman who “seemed like he was having a lot of fun. I asked him if he would train me to be his assistant and he agreed.” Vijayalakshmi, who grew up with filmmaking and film studios in Chennai, India, came into the family business when she completed her education (in interior design, where she studied color) but didn’t have a job. When her elder brother, J. Mahendran, started directing films, she started observing him at work.

On the set for Nenjathe Killathe (J. Mahendran; 1981), Vijayalakshmi saw another woman, named Suhasini, working as an assistant for Ashok Kumar, a well-known cameram...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Prefaces

- List of abbreviations

- Job titles and some useful definitions

- Chapter 1 : How do women become camerawomen?

- Chapter 2: How hard can it be?

- Chapter 3: Documentary: A good and satisfying career choice that is statistically friendlier to women than feature fiction filmmaking

- Chapter 4: Hollywood, Bollywood, independents, and short forms

- Chapter 5: Special skills and creativity

- Chapter 6: Shooting around the world

- Chapter 7: Can camerawomen also be women?

- Chapter 8 : What’s it really like?

- Chapter 9: Magic moments, worst moments

- Chapter 10: What do camerawomen see?

- List of camerawomen whose interviews are included in this book

- Bibliography

- Index

- Back Cover