eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Fan Phenomena: The Lord of the Rings

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 164 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Fan Phenomena: The Lord of the Rings

About this book

Few, if any, books come close to being as beloved – or as ubiquitous – as The Lord of the Rings trilogy. The book delves into the philosophy of the series and its fans, the distinctions between the films' fans and the books' fans, the process of adaptation, and the role of New Zealand in the translation of words to images. Lavishly illustrated, it is guaranteed to appeal to anyone who has ever closed the last page of The Return of the King and wished it to never end.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fan Phenomena: The Lord of the Rings by Lorna Piatti-Farnell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter

08

Lords of the Franchise: The Lord of the Rings, IP Rightsand Policing Appropriation

Paul Mountfort

However, as we shall see, if Tolkien had not sold the multimedia rights to Hollywood the films might never have been made. Consequently it is the California-based Saul Zaentz subsidiary Middle-earth Enterprises that wields worldwide control over film, stage, gaming and merchandizing rights. Inevitably, with hundreds of millions of dollars at stake, the tussle over ownership of ‘the Ring’ has been rancorous, with the heirs to the book rights, Tolkien Estate, and Middle-earth Enterprises aggressively policing their IP (Intellectual Property).

‘There is only one lord of the rings […] and he does not share power,’ intones Gandalf in The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), and the backstory of this franchise is in some ways as gripping as Tolkien’s ring saga itself, which in large part reiterates the Old Norse tale of the cursed ring of Andvari, centrepiece of the Nibelungen-hoard, over which brothers slew brothers and dynastic houses fell. The ring functions as an apt metaphor for the IP rights to the lucrative LOTR books, films, games and associated media, over which those whom I term the ‘lords of the franchise’ have battled it out for decades. Moreover, the resulting spectacle can be viewed as a case study illustrating a historic divergence that has opened up in how we frame and engage with popular texts: whereas on the one hand critical theory and pop cultural practice have increasingly converged to regard such mega-narratives as a kind of common property to be appropriated through practices such as fanfiction, cosplay and other forms of homage and parody, the legal position of their IP owners has increasingly hardened. While the big players, such as Tolkien Estate, Middle-earth Enterprises, Saul Zaentz, New Line Cinema and Peter Jackson have been involved in titanic and well-publicized legal stoushes, even minor infringements can see small-time players ending up in lengthy and costly court battles, as copyright holders seek to police unsanctioned appropriations.

This chapter is divided into three parts: the first recalls the events by which, before his death, Tolkien sold the film rights to United Artists in 1969, thereby setting the scene for a fundamental schism in the way in which rights to different media arms of the franchise would be owned, developed and policed. The second surveys some of the downstream effects of this, and in particular the epic battles centring on the production of the Jackson/New Line LOTR trilogy of films, and the subsequent fallings-out among parties. While these sections are primarily based on media reports and court filings (there has been little published analysis of the issue to date), the third and concluding section uses my own experience to illustrate how an author of a work drawing on the LOTR mythology for a general audience can get caught in the crossfire of this wider IP battlefield.

Sale of the century

The Lord of the Rings novels enjoyed a rapid spike in popularity following full publication by Allen and Unwin in 1955. It was not long before the twin spectres of adaptation and the profit-making machinery of modern media franchises began to bear down on the books. In The Letters of JRR Tolkien (2012), Tolkien mentions talk of animated film offers as early as 1957, and piracy had become an issue by 1965 with Ace Books’s infamous unauthorized US edition.

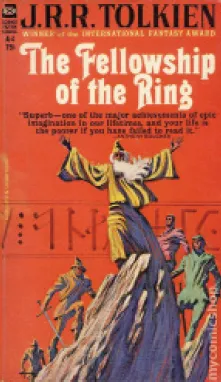

Figure 1: Original US cover of The Fellowship of the Ring.

He wrote to W. H. Auden on 12 May that year of his intention to ‘produce a revision of both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings that can be copyrighted and, it is hoped, defeat the pirates’. By 1969, with thoughts of future inheritance taxes partly in mind, the temptation to cut a deal with Hollywood had become too great: Tolkien agreed to sell the film rights for both to United Artists for £100,000 (equivalent to about £2.5 million today) and a 7.5 per cent share of future profits. The Saul Zaentz Company acquired the rights from United Artists, and in turn formed Tolkien Enterprises – now named Middle-earth Enterprises – which to this day licenses the rights not only to film but all non-print media and merchandizing, including board games, computer games and themed goods.

In retrospect the sale was to drive a cleft through the heart of Tolkien’s legacy: the two towers, as it were, of the Tolkien Estate and Middle-earth Enterprises slug it out to this day over the destiny of the Ring. For underlying the titanic legal battles are fundamental ideological differences. Tolkien Estate and the associated Tolkien Company retain the book rights to The Hobbit and LOTR, and still wield full rights to the other content from the Tolkien universe, including such works as The Silmarillion (1977) and The Book of Lost Tales (1983-1984). As a legal entity, it is comprised of Tolkien’s surviving children (Christopher, sole surviving son, executor of his father’s will and general director of the Estate, and his sister Pricilla), six grandchildren and eleven great-grandchildren. Regarding themselves as the rightful heirs, the Estate wields ongoing control of print publication through the Tolkien Department located at HarperCollins’s head branch in London. It functions in a radically different way from purely commercial IP holders, whose goal is maximum profit. As expressed by grandson Adam Tolkien, ‘Normally, the executors of the estate want to promote a work as much as they can […] But we are just the opposite. We want to put the spotlight on that which is not Lord of the Rings.’ The Estate and associated Tolkien Company thus act as high priests of the canon, unapologetically purging material that violates the purity of the source texts. As Christopher Tolkien stated in an interview, ‘I could write a book on the idiotic requests I have received.’ The French daily Le Monde (the Estate is physically based in the south of France) concluded, ‘He is trying to protect the literary work from the three-ring circus that has developed around it. In general, the Tolkien Estate refuses almost all requests’ (12 July 2012).

It is a world away from affairs on the other side of the Atlantic, or rather, the Pacific Coast, where Middle-earth Enterprises is based, in Berkeley, California. Set up by Saul Zaentz following his acquisition of adaptation rights in 1976, it controls the film, stage, gaming and other media and merchandizing rights. The half-forgotten 1978 animated LOTR film, directed by Ralph Bakshi, for instance, was funded and produced under Saul Zaentz and distributed by United Artists, and a 1982 worldwide licensing deal with Iron Crown Enterprises was the biggest in the history of role-playing games at the time. In 1994 New Line Cinema (technically New Line Film Productions Inc.) was acquired by Turner Broadcasting System, merging with Time Warner in 1996, paving the way for the Peter Jackson-directed trilogy of 2001–03. Not only the films and DVDs but all forms of merchandizing rights, especially games and themed goods, have of course since exploded into multi-billion dollar industries. The current estimated profits of film and DVD sales are evenly matched by the merchandise, at about US$3 billion a piece for a total of $6 billion – equivalent to the annual GDP of Iceland.

Figure 2: LEGO toy set for The Lord of the Rings and Figure 3: Fan illustration of Gollum with the Ring.

Figure 3: Fan illustration of Gollum with the Ring.

The two towers

The Estate had never been happy with the prospect of a somewhat freewheeling adaptation by Peter Jackson defining popular reception of Tolkien’s celebrated masterpiece for a generation or more, but it was the runaway success of the films that paved the road to court for the two parties. Although sales of the books increased by 1,000 per cent due to the success of the film trilogy, the billions of dollars in ticket sales and associated profits led the Estate to revisit the contractual clause that entitled it to 7.5 per cent of profits from any adaptations. The result was a legal case commencing in 2006 titled ‘Christopher Reuel Tolkien v New Line Cinema Corp’. In response, New Line Cinema’s lawyers claimed that the films did not, in fact, turn a profit (studios often offset production costs of movies against the wider expenses of the studio, leading to some fairly creative accounting practices). According to Bloomberg, in early 2009 the Tolkien Estate, the Tolkien Trust and HarperCollins demanded the sum of US$220 million and ‘observer rights’ over subsequent adaptations. Settlement was reached in late 2009, and while the exact sums and payments schedule have not been publically disclosed, the Tolkien Estate was awarded its cut, though crucially not control of subsequent adaptations or merchandise, meaning the 2012–14 New Line/MGM adaptation of The Hobbit was free to go ahead.

Indeed, the first decade and a half of the twenty-first century has seen almost continual litigation, not only between the Estate and Enterprises, but among the various parties with a stake in the film ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Making Fantasy Matter: The Lord of the Rings and the Legitimization of Fantasy Cinema

- The Lord of the Rings: One Digital Fandom to Initiate Them All

- Reforging the Rings: Fan Edits and the Cinematic Middle-earth

- Walking Between Two Lands, or How Double Canon Works in The Lord of the Rings Fan Films

- On Party Business: True-fan Celebrations in New Zealand’s Middle-earth

- Fan Appreciation

- There, Here and Back Again: The Search for Middle-earth in Birmingham

- Looking for Lothiriel: The Presence of Women in Tolkien Fandom

- Lord of the Franchise: The Lord of the Rings, IP Rights and Policing Appropriation

- Writing the Star: The Lord of the Rings and the Production of Star Narratives

- Understanding Fans’ ‘Precious’: The Impact of the Lord of the Rings Films on the Hobbit Movies

- Contributor details

- Image credits

- Back Cover