eBook - ePub

Kurt Kren

Structural Films

- 298 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Kurt Kren

Structural Films

About this book

Kurt Kren was a vital figure in Austrian avant-garde cinema of the postwar period. His structural films—often shot frame-by-frame following elaborately prescored charts and diagrams—have influenced filmmakers for decades, even as Kren himself remained a nomadic and obscure public figure. Kurt Kren, edited by Nicky Hamlyn, Simon Payne, and A. L. Rees, brings together interviews with Kren, film scores, and classic, out-of-print essays, alongside the reflections of contemporary academics and filmmakers, to add much-needed critical discussion of Kren’s legacy. Taken together, the collection challenges the canonical view of Kren that ignores his underground lineage and powerful, lyrical imagery.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1/57 Versuch mit synthetischem Ton (Test)

1/57 Experiment with Synthetic Sound (Test) (1957, 1:23 min, b/w)

Simon Payne

Versuch mit synthetischem Ton is the first of Kurt Kren’s films to be listed in his filmography. It remains one of his most enigmatic films, posing numerous problems for how it might be described. The rhythmic combination of sound and image, which involves cutting repetitively between a handful of images and sounds, suggests a pattern and logic of associative montage, but any interpretation that the film courts hovers between a symbolic resistance to meaning and a level of abstraction that challenges the viewer’s capacity to read the film at all. The following account aims to get to grips with this dynamic of the film, in its oscillation between a certain kind of signification and the range of ways in which it tests the characteristics of the medium and counteracts meaning.

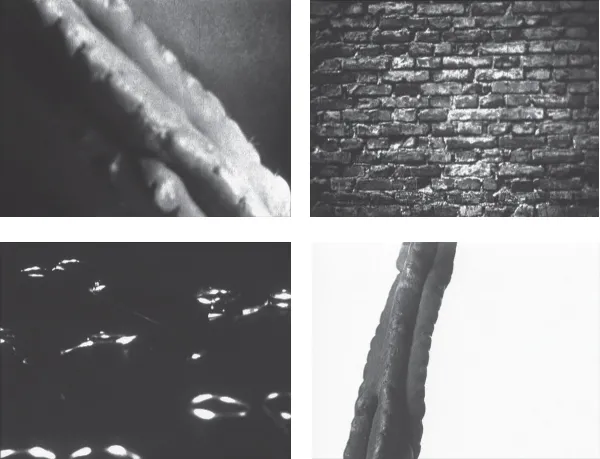

The images in the film, each several seconds long, comprise shots of a cactus; different brick walls (at a range of distances); the muzzle of a pistol that is pointing at the camera; and a rapid-fire, single-frame sequence that animates numerous pairs of scissors. The film’s sound was created by scratching into the emulsion of the soundtrack area that runs along the edge of the filmstrip. There are broadly two different textures of scratched sound: one is louder and has a higher pitch, and generally accompanies the images of brick walls; the other is duller, more muffled, and generally accompanies the shots of the cactus. A third characteristic of the soundtrack is the use of silence, which usually accompanies the image of the pistol. In conjunction with the scratched sounds, the silent passages become a component in the rhythmic structure of the piece, which prefigures the tighter and more abstract patterns that underpin some of Kren’s later films.

A number of the elements in the film have a haptic quality. The abrasive sound is one such element. Ordinarily in sound recording there is a distance between the microphone and the source of a sound. In this instance, however, the sound was produced through a direct contact with the filmstrip and this proximity is audible in its timbre. One might associate the scratched sound with the spines of the cactus, but in its pure physicality the soundtrack is also a testament to film’s indexicality. In effect, the scratched sound is a tracing of the action made by the filmmaker’s hand. In this respect it is analogous to a shot made with a handheld camera, but even more direct. The significance of sound in this film is, in fact, announced from the start. The title card TEST appears superimposed over a shot of a fading light bulb filament. As the light source, and hence the image, disappear, an abrupt cut introduces the film’s prominent soundtrack. Given that the sound derives from an optical soundtrack – which is produced by a light source that shines through the scratched surface of the emulsion – the sound as well as the image relies on light, but this first sequence of the film declares a reversal of film’s usual order, in which the image is thought of as primary.

1/57 Versuch mit synthetischem Ton (Test)

The other elements in the film that appeal to touch are the images of objects that would be within one’s reach, principally the cactus and the close-up shots of the wall. At the same time, the spines of the cactus are a repellent, and the brick wall, especially in the wide shots, represents an overwhelming barrier. If one thinks of the cactus and the wall as signs, or symbols, they function as images that ward off the viewer. The unaccommodating sound could be thought of as operating in a similar manner. The muzzle of the gun, pointing at the viewer, is more targeted and blunter still. In the last shot of the film, the gun tilts forwards, towards the bottom of the frame, in a dismissive fashion that signals contempt. In these aspects, the act of fending off, or resisting the viewer, is symbolically encoded in the film.

Other readings of the film have gone much further. Peter Tscherkassky, for example, has interpreted it as ‘recording feelings surrounding a tragic love’. Having been prompted by a comment made by Kren, regarding the personal and intimate nature of the film, he reads the protrusion and furrows of the cactus as phallus and vulva simultaneously, the wall as the site of an execution, and the scissors as instruments of castration. The film needn’t be seen as an abstract psychodrama, but Tscherkassky doesn’t necessarily overstate the provocative nature of its imagery, especially in light of some of Kren’s subsequent films. One could trace a line between the implied violence in Versuch and later films including 20/68 Schatzi and 24/70 Western, for example, which depict partial images of a Nazi death camp and the My Lai massacre respectively. Likewise, the suggestion of a castration complex resonates with Kren’s films of the Aktionist performances that often hinge on a bathetic sadomasochism. But I also want to suggest that reading Versuch as an abstract psychodrama is slightly reductive.

While Versuch undoubtedly solicits interpretation, the formal characteristics of the film, which emphasize contrasts in tonality, offset framings, and unusual focal planes, hinder any reading that might be thought of as transparent. The way that the gun is framed and lit, for example, makes it almost unrecognizable, and consequently difficult to decipher. Occupying a small portion of the frame in the bottom right-hand corner, mostly in darkness, the blank black background is the dominant feature of the shot. In so far as the image of the gun functions as a metaphor for the camera’s gaze, turned towards the viewer, it is a reflexive image, but one in which the focus is displaced and obscured rather than iconic and self-evident. The scissors are another example of a reflexive image, given that the film is partly about editing, but like the gun/camera they are also difficult to see. Between the highlights and the darkness of the high contrast imagery, there is very little definition in the image that describes the scissors’ form. The number of scissors that appear in this sequence is also unclear, made indeterminable by the fact that they were shot using single-frame filming with shifts in position from one frame to the next. This sequence is also something of a joke in the film: it is the fastest cut sequence in the film, and offers a metaphor for the tools of the editor, but it is a sequence that must have been edited in-camera rather than cut and spliced subsequent to shooting.

Various aspects of Versuch mit synthetischem Ton reflect the potential of the medium to encompass aesthetic characteristics that are polar opposites. (The same is also true of a number of Kren’s later films, including 4/61 Mauern Pos.-Neg. & Weg and 22/69 Happy End.) In contrast to the images of the walls, for example, which could well be stills, the scissor sequence reminds the viewer of film’s 24 frames-per-second rhythmic pulse. Flatness and depth are similarly opposed: while the shapes made by the scissors appear to race across the surface of a tabletop, most of the other objects in the film are shot in a plane that renders them flat onto the screen. The shots of the wall render the flattest imagery in the film, but a dialectic is set up here too, because the close-ups reveal a significant relief in the surface of the wall across the brickwork, mortar and lichen. Another dynamic of the film concerns framing. Again this is exemplified by the wall, which carries beyond the edges of the frame at the same time that it limits one’s sense of the off-screen space beyond or beside it.

Curiously, in nearly all of the shots featuring the cactus, the dark background is more in focus (or sharper) than the cactus itself. The images of the cactus are primarily examples of the modelling and sculpting of form in light and dark, to produce imagery that spans clarity through to obscurity. In addition, these shots also function as transition between dark and light, or vice versa. In each instance, the cactus starts off out of frame and then it is brought through the frame by a handheld sweep of the camera that pans from a darker patch of wall, across the half-lit surface of the cactus, to a lighter patch of wall. On a purely formal level, the manner in which the cactus arcs through the frame acts as a graphic wipe. A stark contrast to these shots, which are activated by camera movement, is the final image of a cactus, and the penultimate shot of the film. In this shot the tonal quality attributed to figure and ground is reversed, as is the relationship between movement and stasis. A crisp, still shot of the cactus, evenly lit, stands erect against a bright white background. Interrupting this otherwise static image, it is just possible to glimpse a fly speeding through the picture – an incidental feature of the shot presumably, but a happy accident, which takes on significance as the only moving object in the film.

There are two respects in which the film courts abstraction. On the one hand it seems to offer the viewer an abstract message, inviting them to decode the connotations and meaning of its imagery. But if there is a message in the film, paradoxically it is one that iterates ways to fend off the viewer. On the other hand, it engages with abstraction on a formal level (in relation to lighting, focus, framing, movement and depth) and an order of recognition that is quite distinct from any meaning that might be made. This aspect of the film includes those means with which it successfully obfuscates and problematizes its own reading. My suggestion here echoes the claims that Peter Gidal has often made in articulating the aims of structural/materialist film, and his own practice, heralding a dialectic in which a tension would be set up between the material characteristics of a film and its capacity for representation. But in contrast to Versuch mit synthetischem Ton, Gidal’s films are hardly imagistic at all – tending towards ‘signifiers approaching emptiness’ – and certainly run counter to anything approaching associative montage. The most significant of Kren’s films for Gidal, and Malcolm Le Grice before him, were 3/60 Bäume im Herbst (Trees in Autumn) and 15/67 TV – films in which formal processes and structures come to the fore. The imagery in many of Kren’s films is charged and resonant, but few could be described as symbolic, and few use strategies that directly imply meaning. An exploration of symbolism is one of the primary tests that Kren undertakes in Versuch. In subsequent films, meaning and association are configured rather differently.

Kurt Kren and Sound

Gabriele Jutz

Of the 53 films that Kurt Kren completed between 1956 and 1996, only eight utilized sound. Kren himself repeatedly underscored the deliberate use of silence in his work: ‘I am more visual than audio-visual,’ he stated in an interview with Peter Tscherkassky (Tscherkassky 1995: 127; see Tscherkassky’s Interview with Kurt Kren in this volume). For Kren, silence represents a genuine option – not an absence, but rather a predilection for the visual, while added sound always harbours the danger of competing with the image. He was also convinced that sound could be contained within the purely visual realm citing rhythm as an example that is both auditory and visual. In addition to these aesthetic concerns, one can speculate that Kren’s concentration on the visual came about due to a chronic shortage of money. In the same way that his method of in-camera editing – or in the case of films edited outside the camera, a shooting ratio close to 1:1 – allowed him to make economical use of filmstock, the lack of sound in most of his films can also be seen as the expression of an extreme economy of means.

In the light of its sparseness, the use of sound in Kren’s films is all but ignored by critics and scholars alike. This lack of attention overlooks the fact that Kren has made a significant contribution to the ‘audio-visual’ aesthetics of film. To reduce this seemingly image-oriented filmmaker to the visual aspect alone means shutting one’s eyes and ears to the fact that sound (and its absence) represents as open a field for experimentation as the image itself. A consideration of the sonic dimension of his films complicates the received picture of Kren’s oeuvre.

First, it is worth noting that even the screening of a silent film is never a purely visual experience. A number of studies have shown that during the so-called ‘silent period’ the presence of sound was ubiquitous: early film screenings were often accompanied by a broad range of instrumental, vocal or mechanical sounds that were either improvised or pre-planned. And the practice of adding sounds to an otherwise silent film is not restricted to the silent era; it continues to be an integral part of ‘live’ cinema practices, including expanded-cinema and its contemporary counterparts. On a few occasions, Kren’s silent films were shown accompanied by recorded music or live music. Thanks to Ralph McKay, we have a wonderful record of ‘The Kurt Kren Relief Concert’, a show organized for Kren’s benefit during a time when he was touring with his films in the United States while living out of his car. The benefit was organized by McKay, Bill Steen and U-Ron Bondage, the singer of the Texan punk band Really Red. The event took place in downtown Houston at Studio One on 29 January 1983:

The place was packed when the show started with TREES IN AUTUMN, its soundtrack at maximum volume. Program 1 continued with a selection of Kurt’s more formal films – ASYLUM, T.V., TREE AGAIN, etc. These ran with recorded music, probably AFRICAN HEADCHARGE (Kurt’s usual choice), and finished with the transitional SENTIMENTAL PUNK. The reception was already extraordinary before the program accelerated into nine Aktion films in thirty-eight minutes – MAMA AND PAPA, SELFMUTILATION, LEDA AND THE SWAN, etc. These were accompanied by a raw industrial live improvisation by REALLY RED – guitar/Kelly, bass/John Paul, drums/Bob, U-ron/synth, Dennis/sax. The pumped-up crowd, and the musicians, were surprisingly jarred by Kurt’s films. Kelly was downing a burger while performing and practically lost it when he looked up to see Kurt’s ‘eating, drinking, pissing, shitting’ SEPTEMBER 20. [...] The program drove on with a full-force REALLY RED set and finished with one last film – KEINE DONAU, in case anyone was left wondering.

(McKay 2000)

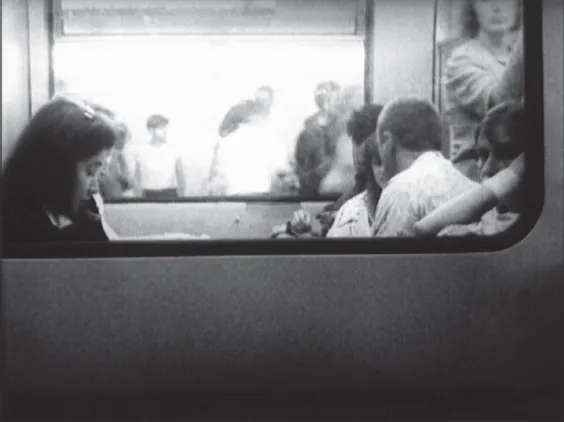

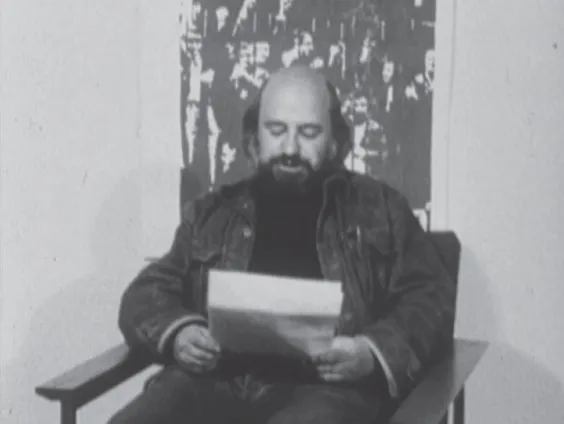

46/90 Falter 2

29/73 Ready-made

Really Red even wrote a song about Kren, entitled ‘Ode to Kurt Kren’. Its refrain is ‘Frame to frame on celluloid. Kurt Kren came from Austria’.1 After the punk underground’s tribute to Kren, whose aesthetics paralleled that movement’s own, Kren continued to occasionally show his films alongside the incendiary Texan music scene of the time. For the period that followed Kren’s return to Vienna in 1988, only one more screening with live music has been noted: the premiere of 48/94 Fragment W. E. on 1 June 1995 – a film of only 13 seconds screened as a loop and accompanied by the painter Wolfgang Ernst’s improvisations on the violin.

As far as Kren’s ‘true’ sound films are concerned, a standard recorded soundtrack can be found in four films: 23/69 Underground Explosion, a reportage on an underground festival, accompanied by music by Karl-Heinz Hein; 29/73 Ready-made, which consists of outtakes from a television studio recording, where Kren reads letters that Groucho Marx had written to Warner Bros.; 46/90 Falter 2, an advertisement spot for the Vienna city newspaper Falter, whose sound was conceived by Wolfgang Ernst; and 47/91 Ein Fest (A Party), where Kren recorded the ambient noise of a party given by the Austrian broadcasting corporation, ORF, on the occasion of the program series Kunststücke celebrating its jubilee. (The latter two of these films were commissioned works, and I will not review them specifically.)

The most intriguing sound practices in Kren’s oeuvre are those that free the filmmaker from the use of a recording device. One method to circumvent recording is handmade sound, whether scratched or drawn onto the filmstrip, as shown in 1/57 Versuch mit synthetischem Ton (Test) (Experiment with Synthetic Sound) and 3/60 Bäume im Herbst (Trees in Autumn). Another method is to appropriate pre-existing sound, as 44/85 Foot’-age Shoot’-out and 49/95 tausendjahrekino (thousandyearsofcinema) demonstrate. These two practices – handmade sound and appropriated sound – establish a distinction between two opposing models of artistic authorship, which relate to Johanna Drucker’s characterization of the artist’s role as a ‘producing subject’ in relation to two dominant strains: one ‘expressive’, the other ‘conceptual’.

This split marks the distinction between the artist as a body, somatic, with pulsations and drives ... and the artist as intellect, thinking through form with the least amount of apparent individual expression, anti-subjective and antiromantic.

(Drucker 1994: 122)

In what follows, I address Kren’s most interesting contributions to the acoustic dimension of film by dealing first with handmade sound and second with appropriated sound, from a perspective that addresses formal as well as associated historical, technical and political issues.

Handmade Sound

Kren’s two films with handmade sound both originate from his early period. The first, 1/57 Versuch mit synthetischem Ton, originally entitled Test, was made in 1957. This barely one-and-a-half-...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Not Reconciled – The Structural Films of Kurt Kren

- 1/57 Versuch mit synthetischem Ton (Test)

- Kurt Kren and Sound

- 2/60 48 Köpfe aus dem Szondi-Test

- 3/60 Bäume im Herbst

- 3/60 Bäume im Herbst

- Time-Splits: 4/61 Mauern pos.-neg. & Weg and 31/75 Asyl

- Strategies in Black and White: 4/61 Mauern pos.-neg. & Weg and 11/65 Bild Helga Philipp 67

- 5/62 Fenstergucker, Abfall, etc.

- 15/67 TV

- 17/68 Grün-Rot

- Negation and Contradiction in Kurt Kren’s Films: 32/76 An W + B, 18/68 Venecia Kaputt and 42/83 No Film

- 20/68 Schatzi

- 31/75 Asyl

- 37/78 Tree Again

- Miscellaneous Works and ‘Bad Home Movies’

- Vernacular Studies: 49/95 tausendjahrekino and 50/96 Snapspots (for Bruce)

- Colour Frame Enlargements and Pages from No Film

- Reprints and Facsimiles

- Collected Writings on Kurt Kren

- Reviews of 31/75 Asyl, 15/67 TV and 28/73 Zeitaufnahme(n)

- Interview with Kurt Kren

- Notes on Kren: Cutting Through Structural Materialism or, ‘Sorry. It had to be done.’

- Interview with Kurt Kren

- On Kurt Kren

- Lord of the Frames: Kurt Kren

- Interview with Kurt Kren

- Apperception on Display: Structural Films and Philosophy

- Filmography

- Notes on Contributors

- Back Cover

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Kurt Kren by Nicky Hamlyn, Simon Payne, A. L. Rees, Nicky Hamlyn,Simon Payne,A. L. Rees, Nicky Hamlyn, Simon Payne, Al in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.