![]()

Section Two

Applications — The use of the digital in the everyday

![]()

Chapter 5

Identity management, premediation and the city

Sandra Wilson and Lilia Gomez Flores

![]()

Introduction

We are now experiencing an era of ‘persistent identity’ (Poole 2010), in which our identity is constantly ‘on’. Almost all our movements are routinely and smoothly monitored while we interact with CCTV cameras, withdraw money from ATM machines, swipe identity cards for entering buildings, and buy goods and services using credit/debit cards. Within a highly digitalized society, our identity is key to giving us access to a growing range of services and benefits, thereby increasing the need to ‘manage’ our identity.

Identity management (IM) is a term only recently coined (since approximately 2004), and yet it is slowly permeating our daily lived experience. Post-9/11, governments and corporations are placing a greater emphasis on security in an attempt to prevent more terrorist attacks of every kind. Along with the fact that we conduct an increasingly large part of our everyday interactions remotely – online via either computers or mobile devices – this has forced the development of various forms of IM solutions.

The nature of cities is constantly changing and being contested in a continuous, never-ending process of mediation from different disciplinary points of view. In this chapter, we analyse the interactions between individuals and their identities in the city from an angle of premediation. It is here that possible future experiences are first encountered through popular media, affecting our relationships with the urban environment.

Identity management

As part of our research (IMPRINTS 2014), we searched and analysed different scenarios of IM, which indicated that there were three forms of human interaction that need identification or authentication (Figure 1):

1. Between individuals.

2. Between individuals and organizations.

3. To give individuals access to their possessions (objects) and or/spaces.

In addition, these scenarios present three different instruments to introduce ourselves (identify) and prove who we are (authenticate):

Figure 1. Forms of IM

1. Based on knowledge or memory (e.g. PIN codes, passwords).

2. Based on tokens (e.g. passports, customer cards, smartphones).

3. Based on body features (e.g. biometrics, implants).

The combination of interactions and instruments constitutes a ‘field’ of representation and mediation. All the scenarios have positive/optimistic and negative/pessimistic varieties.

Our research found that, as a method of authentication, passwords and PIN codes are usually considered neither very convenient, nor very safe. As such, some people expect that they will merge with other authenticators and eventually disappear. We will therefore focus this chapter on the use of tokens and body-based biometrics.

Smart token scenarios

The use of RFID and microelectronics such as Arduino enable the creation of a variety of smart tokens. An example is the London Underground Oyster Card, which allows its users to travel around the London transport system relatively easily. Nowadays, RFID is used in several other token systems, such as smart bracelets for use at festivals (BBC Newsbeat 2012). Already used in Europe, designers say the wristbands wipe out ticket fraud and touting, and can be loaded with cash to pay for goods on-site. This has parallels with the use of ‘smart watches’ like ‘Rumba Time’ (Price 2011), which lets you carry medical and payment information on your wrist. Clothing is also expected to be utilized increasingly for health and leisure information, as well as by other types of organizations. SmartLife (2014), for example, has developed an advanced wearable computing technology that interfaces seamlessly with the body to provide remote, real-time, always-on access to body data (via smart pants). The company’s patented SoftSensor smart fabric incorporates ultra-thin dry sensors that deliver highly accurate information on a broad range of vital signs and body movements. These data may then be transmitted via connected devices to enable innumerable cloud-based hyper-personalized services in markets such as healthcare, sports, hazardous environments and the military. Supermarket chain Walmart (Murph 2010) have placed RFID in individual garments to help apparel managers know when certain sizes and colours are depleted and need to be restocked. In S. Korea, commuters can now shop at virtual supermarkets by mobile-scanning QR codes on murals of groceries plastered across metro platforms (YouTube 2011). The groceries are then delivered to the commuters’ homes shortly after they return. Thousands of students in Brazil are now required to wear a shirt that text messages their parents when they do not show up for class (Nguyen 2012). The T-shirts work in a similar way to the tracking devices sometimes used to locate lost pets: a chip that is built into the clothing provides data to a central computer programmed to send updates to parents about their child’s whereabouts via text message. Whenever the child enters the school, it instantly sends confirmation of the arrival; if they do not show up within 20 minutes of classes starting, parents will receive an alert that says: ‘Your child has still not arrived at school’.

Interestingly, some individuals are starting to hack these RFID chips for their own purposes. In London, for example, the Urban Wizard (Whitby 2012) has removed the chip from his Oyster Card and placed it at the end of his ‘magic’ wand, wowing spectators with his supposed magic and ‘wizardry’. These chips have also been placed into rings (although Transport for London has fined those caught doing so, as the cards are technically Transport for London’s personal property!).

When implanted within the body, RFID chips can also carry financial information or provide access to spaces (for example, within nightclubs and bars), as well as providing access to cars, homes or workspaces (RFID Journal 2005). However, we do not have to be chipped or carry a mobile device in order for our bodies to be recognized within the city.

Body-based biometrics

The research exposed an increasingly common situation in which people gain access to urban spaces, and government or corporate services through authenticating body-based biometric features (e.g. fingerprints, palms, iris, face, voice, gait, etc.). Driven by a strong and growing industry, the use of biometrics in urban settings is rapidly expanding; ever more bodily features are being used for authentication, including body odour and buttock prints, but more significantly, DNA.

Fingerprints are now commonly used in many schools and colleges to pay for lunch or sign in for classes (YouTube 2008). Japanese company OMRON (OMRON Global 2012) has now developed hand gesture recognition in conjunction with face recognition technologies. Alongside other biometrics, such as fingerprinting, iris recognition is now commonplace in airports and at borders around the world. Tools such as face recognition are now in the US workplace; for example, Garden Fresh Restaurant Corp (Ganeva 2011), which runs franchises of the buffet restaurants Souplantation and Sweet Tomatoes, announced it had installed this technology at 122 locations across 15 states in 2011. Cognitive biometrics studies how different individuals might be identified by their brain’s reactions to various images, such as one’s mother (Freeman 2012).

Gunshot recognition (Safety Dynamics 2014) is another recent development. In this case, microphones can pick up the sound of a shot being fired in a metropolitan area within one second of the shooter pulling the trigger; a camera then zooms in on the location and authorities instantly have some idea of who and what they are dealing with:

‘So in most cases, the shooter hasn’t even begun to drop their arm yet and we’re already looking at the scene,’ said Wayne Lundeberg, Chief Operating Officer of Safety Dynamics: a Tucson-based company with gunshot detection technology in the US and Mexico.

(Safety Dynamics 2014)

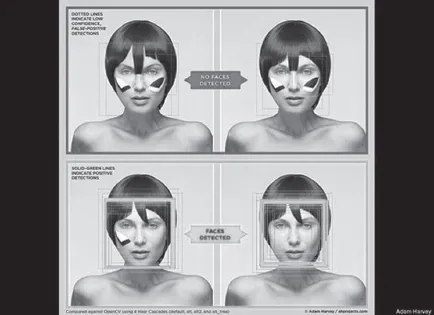

This is also the area where the strongest public and political concerns for the future have been expressed, especially with respect to a potential loss of privacy, issues surrounding data protection and the export of these technologies to oppressive regimes. It is within the area of art practices that we find most discussion about these issues and their increasing leakage into other areas of public life. CV Dazzle (Harvey 2014) by New York-based artist Adam Harvey, for example, is a camouflage created from computer vision algorithms, allowing users to avoid the legal issues associated with the wearing of masks through a clever use of make-up and hair styling (Figure 2). The name originates from a type of camouflage used during the First World War. This approach has not yet featured in an act of public resistance; however, culture and fashion magazines (e.g. DIS, a fashion art and commerce publication) have used it in their styling. In an interview for theartblog.com, Adam Harvey (cited in Armpriester 2011) describes CV Dazzle as ‘the ticket into the invisible class – men, women and children deleting themselves from the digital eye’.

Figure 2: ‘CVDazzle’ by Adam Harvey.

Similarly, the FAGFACE mask by American artist Zach Blas (2014) – part of his Facial Weaponization Suite – develops forms of collective and artistic protest against biometric facial recognition (and the inequalities these technologies propagate) by making masks in community-based workshops that are used for public intervention. The mask is a response to scientific studies that link determining sexual orientation through rapid facial recognition. This mask is generated from the biometric facial data of many queer men’s faces, resulting in a mutated, alien facial mask that cannot be read or parsed by biometric facial recognition technologies.

In a video interview with the authors last year, Blas highlights how some of these forms of IM are being used without an individual’s knowledge or authorization. For example, in 2001, the Tampa Bay police used facial recognition technologies to search for criminals and terrorists during the Super Bowl, resulting in several arrests (but no charges). Blas also highlights the dangers of these technologies and databases being used for other purposes, such as to identify homosexual men purely from their faces.

This opposition has also been expressed in the sousveillance movement. Steve Mann (2004) established a differentiation between surveillance and sousveillance: ‘surveillance’ is French for ‘to watch from above’; it typically describes situations where person(s) of higher authority (e.g. governments, institutions, police, etc.) watch over citizens, suspects or shoppers. Foucault (1977) described it as the higher authority to be ‘godlike’, rather than down at the same level as the individual party or parties under surveillance. Mann, meanwhile, describes it as the capture of multimedia content (audio, video or the like) by a higher entity that is not an equal of or a party to the activity being recorded. The author has suggested ‘sousveillance’ as French for ‘to watch from below’: the term refers both to hierarchical sousveillance (e.g. citizens photographing police, shoppers photographing shopkeepers, and taxi passengers photographing cab drivers), as well as personal sousveillance (e.g. bringing cameras from lamp posts and ceilings down to eye-level for human-centred recording of personal experience). Sousveillance has two main aspects: hierarchy reversal and human-centeredness, and these often interchange (for example, someone who drives a cab one day may be a passenger in someone else’s cab the next). The artist Wafaa Bilal (Hicks 2012), for example, has implanted a camera in the back of his head to ‘watch-the-watchers’, exploring sousveillance as a way to balance the sense of power and control.

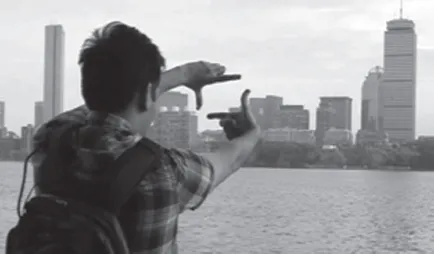

Figure 3. Pranav Mistry wearing the SixthSense device.

Figure 4. Pranav Mistry and the SixthSense device interacting with the city.

Figure 5. Pranav Mistry and the SixthSense device interacting with other people through the Internet of Things.

Other developments include wearable cameras like the one used for the SixthSense (see Figure 3), developed by Pranav Mistry (2012). SixthSense is a gestural interface device comprising a neck-worn pendant that contains both a data projector and camera. It combines the cameras with illumination systems for interactive photographic art, and also includes gesture recognition (e.g. finger-tracking using coloured tape on the user’s fingers). All this combined technology gives the wearer a sense of control and interaction that goes beyond sousveillance – although sousveillance is an always-present option. It gives the user the opportunity to navigate the city creating his/her own experiences with the urban environment and its inhabitants (see Figure 4). It has the possibility to wirelessly connect to the Internet of Things, smoothly weaving connections between the wearer and other people and/or objects by retrieving available online information, such as personal data and product characteristics (see Figure 5).

Premediation

In the aftermath of 9/11, Grusin (2010) observed a new media pattern emerging in the United States and then expanding worldwide. He called it ‘premediation’ and explained that it ‘works to prevent citizens of the global media sphere from experiencing again the kind of systematic or traumatic shock produced by the events of 9/11 by perpetuating an almost constant, low level of fear or anxiety about another terrorist attack’ (Grusin 2010: 2). Premediation is also described as the way in which multiple futures are brought to life in the present. Many of the scenarios discussed above are also being premediated within film and television, the most obvious example being the film Minority Report (Spielberg 2002) starring Tom Cruise, which provides examples of iris recognition being used to target personalized advertising whilst shopping. Research partners Turner, van Zoonen and Harvey (2013) highlight how film and television are key contributors to this process of premediation, whereby the scenarios they present do not prescribe certain meanings around IM, but create and delineate a so-called ‘imaginative horizon’. News, popular culture and social media are no longer concerned with a representation of recent or live events, but are obsessing instead about what might happen next, including future identity management scenarios in the city.

We can see examples of ID tokens being premediated in the first Bourne Identity (Liman, 2002) film, where Jason Bourne has a stash of fake ID (its location revealed in the first place by an implant in his hip); while in RED (Schwentke 2010), another former CIA operative takes a sledgehammer to the foundations of his house, unearthing a box filled with cash and IDs. In terms of biometrics, Gattaca (Niccol 1997) demonstrates how blood tests are not only used to determine a person’s identity (in cases where it is the only – or only certain – way) so as to permit access to buildings on a daily basis, but citizens are also effectively graded from conception according to their genetic make-up. This premediation of IM practices and technologies associated within the city has an impact on both our experience of the city and the ways in which it is mediated, regardless of whether these practices and technologies exist in any given reality or not.

Mass media, user-generated content and (pre-)mediation

It is important to make a distinction between what is considered mass media and what is deemed user-generated content (UGC). Although they both usually go toge...