![]()

Chapter 1

A Stage for the Image: Occupying Space, Multiple Screens

![]()

During the 1920s, the Russian avant-garde artist El Lissitzky, who taught at the Bauhaus, conceived spatial apparatuses in which painting and sculpture together reached beyond their assigned place to constitute total artworks, inviting the viewer to move around and manipulate them. In the spirit of the experiments being made at the same time by Vladimir Tatlin in his Konterrelief and Kurt Schwitters in his Merzbau, he created a new way of uniting the space of the work with the space of its presentation. The Abstract Cabinet (1927–28) that he created for Alexander Dorner at the Landesmuseum in Hannover was a revolutionary conception and art historical landmark. Its display gave spatial extension to the pictorial researches of Malevich, Mondrian, Moholy-Nagy, Baumeister, Van Doesburg, Gabo and Lissistzky, brought together by an enlightened curator. The visitor was confronted with works that defied the flatness of the wall, positioned within a display device (sliding panels) that he was asked to activate, thereby engaging with other modalities of reception. El Lissitzky’s position was radical: ‘Space: that which is not looked at through a keyhole, not through an open door. Space does not exist for the eye only: it is not a picture; one wants to live in it’.1 He sought to wrest viewers from their passivity with regard to artworks and make them active in the process of their perception. This project, which was also political in an age when capitalist society had started to anchor the individual in a consumerist relation to goods and images, has numerous echoes in today’s world.

Artists have made abundant use of the immersive resources offered by new technologies to create artistic experiences pursuing the direction mapped out by El Lissitzky, inviting viewers to enter the space of the work both physically and mentally, to inhabit it for the duration of their visit, and even to activate it when interactivity is used. By affirming the connection between the stage and the exhibition gallery, video installation makes the viewer an actor who moves around between the works and whose experience of reception becomes performative. Entering the space of projection, we are immersed in an imaginary that, while constructed in and by the image, also exceeds the image. Walking around the screens, deciding to stop or keep moving, to sit or to stand, to look at one work or at several, to isolate or move the images round, to listen or to put the headphones back—all these choices allow the beholder to choose their perceptual position with regard to the works, while plunging them into an immersion that can often be destabilizing. Françoise Parfait has highlighted this aspect in her study of video installations, ‘Disorientation is one of the stumbling blocks of the spatio-temporal experience offered the visitor, often beginning with physical disorientation and ending in a mental disorientation conducive to thinking about the conditions of perception and language’.2 The structure of the video installation, with its ability to combine moving images, the spatialization of sound and architectural devices, offers a privileged space for thinking about our relation to representation. By peopling the exhibition space with works that go beyond the framework of the image, David Claerbout, Julian Rosefeldt, Ugo Rondinone and Sebastian Diaz Morales offer immersive, stimulating experiences of seeing that are constantly calling attention to the relation to the body and the gaze that is their underpinning. Through them there emerges a way of thinking about perception and a questioning of the relations to the world that subtend it.

David Claerbout: Porous Temporalities

Because of its aural dimension, artists and curators often prefer to show video work in closed, isolated spaces, commonly known as the black box, imitating the cinema. This immersion in darkness helps the spectator to concentrate by keeping out unwanted interference. By creating a projection space that, in contrast, allows light around the screen, and by letting the sound contaminate the general atmosphere of the room, David Claerbout (Belgium, born 1969) is one of these artists who are questioning our relation to the moving image.

Moving into a Claerbout installation, one is struck by the silence, the appearance of immobility, as if time were suspended. One treads more discreetly, not to escape but in response to the rhythm emanating from the work. The image inhabits the space, marking it with its distended temporality, in a coming and going between photographic fixity and the motion of video. There is something fundamental about the interstice into which this artist inserts his practice, in that it is all a matter of questioning and, above all, metamorphosing, the paradoxical impression that we have when looking at a photograph. The fixed image of a past moment is the sign that something has been, but this certainty also brings discomfort because of the gaping holes that, at the same time, we open in our memory’s outer reaches. In his works, Claerbout offers to prise open the density of time, to reanimate dead things. We are far from the action of desacralization or, on the contrary, resurrection. The images chosen by the artist are not icons before which we lament their loss; they are resplendently banal: breakfast al fresco, a tree, a couple dancing, a motorway interchange. Each piece is autonomous, has its own alchemy of discreet movement and light allowing uncertainty to creep in with great subtlety. We are immersed in the movements of the leaves of a tree, arrested by the eyes of a little girl who turns her head and greets us, struck by the projected image of a man and woman dancing.

Experiencing the works is key to understanding how installations are never closed in on themselves. The exhibition space is porous, the installations open to one another, the partitions between them full of holes; these panels act not to separate but to create ricochets, playing on transparency and opacity in order to avoid the isolation of works that one would like to appreciate in their continuity and diversity, which is the drawback of the conventional display apparatus. This is how Claerbout describes the layout of his 2007 solo show at the Pompidou Centre in Paris,

David Claerbout, Shadow Piece, 2005. Installation view at Pompidou Center, Paris, 2007. Photo: Georges Meguerditchian. Courtesy of the artist.

Here […] the spectator enters through a dark space painted black. On the way in they are confronted with one of the works in the exhibition, Shadow Piece, projected onto a translucent screen. When they pass through the screen, everything is in white, transparent, with no constructed ‘cube’ to disrupt the gaze.3

The whole exhibition is thus conceived as a great stage on which projections are articulated. The picture walls/screens structure the space but do not close it, as they are always traversed by light. In the work that confronts visitors as they enter, Shadow Piece (2005), a film shows people walking past a glass building that they are unable to enter, whereas their shadows can. This visual effect created by means of two distinct shots echoes the viewer’s position with regard to the exhibition. They too can walk between images but never enter their place, while their mind can, like a shadow, become sucked into the projected territories. For Claerbout, the handling of sound is particularly important as a means of avoiding confusion. Like the images, the sounds coexist and do not need to be isolated. This gives the viewer the sensation of being on an open stage where signs appear as and when they move around, cohering and coming apart as they do so. In some pieces, headphones allow visitors to listen to a dialogue and those accede to another level of interpretation. Benches placed around the exhibition invite participants to settle and become drawn into the images, for their gaze remains mobile. The general impression is dominated by a feeling of lightness, of the fluid relation between pieces, bestowing genuine unity on the exhibition experience.

David Claerbout. Installation view at Pompidou Center, Paris, 2007. Photo: Georges Meguerditchian. Courtesy of the artist.

In an article published in an important anthology, Art of Projection (2009), Mieke Bal analyses the intense feeling of immersion experienced when reacting to a video installation, and the hypnotic power that this has, quite independently of its narrative thrust.4 She emphasizes the similarity between these works and the workings of dream, when subjectivity is absorbed in the scene of the unconscious. In both cases, the subject finds itself at the centre of a visual structure freighted with emotions, moving in the image without directing it, approaching the status of an actor on stage. Psychoanalysis has demonstrated the value of the theatrical model as a way of thinking about the working of dreams, and Bal uses it here to help get a handle on the effect of video installations. When we enter a Claerbout exhibition, we do effectively experience the emotions she describes; the narrative meaning eludes us but the rhythm of the images grips us strongly, carrying us along in a powerfully oneiric progress. We perambulate the picture walls with a feeling that we are taking part in a representation that speaks primarily to the senses, in which the body is an essential support for the reception of the works. If the looped videos seem totally independent of the viewers, and do not seek to prompt their participation, viewers do need to be affectively receptive and to wander round the exhibition space for the artistic experience to crystallize on its stage. The imposing scale of the projections, closely related to the dimensions of the exhibition space, places the viewer in a frontal relation to an image that goes from floor to ceiling. The images invite them to mentally penetrate their spaces of representation, for example to join in the shadow of that old woman swaying gently back and forth in her Rocking Chair (2003), whose gaze occasionally meets their own. But this impression is only fleeting, and soon we are back outside the image. The handling of the exhibition space is not designed to include the beholder but to prompt a state of uncertainty in which they question their relation to the works.

David Claerbout, American Room, 2009. Courtesy of the artist.

With The American Room (2009), Claerbout extends this reflection on the stage space in another way, by focusing on a classical concert and the codes that structure its reception. Slow tracking shots show us an audience listening to an opera singer in religious silence. The recital is being given in an official venue: we see the American flag. The camera dwells on individual, concentrating faces, sometimes with a hint of a smile, their poses powerfully evoking bourgeois codes. The viewer is drawn into the emotion that seems to have brought all these people together, and this absorption is enhanced by the soundtrack and the visual rhythm. The singer is about to start Amazing Grace, a very popular Christian hymn. However, the music played by the pianist slowly fades before the concert can really start, so that silence gradually takes over again. The camera now moves around the auditorium, alternating between different viewpoints, allowing the gaze to dwell vaguely here and there. The music then strikes up again with the American national anthem, followed later by an Elton John song, all giving the scene a very conservative feel. A guard stationed at the entrance also seems captivated by the concert. The movement of the camera, the sound, the gentle light coming in through the windows and playing over the faces all confirm the theatrical dimension. But something important escapes the spectator here, upsetting them and preventing them from becoming fully immersed in the gathering. The particular relation between fixity and movement seems extremely problematic: as the camera eye peruses the scene, alternating between shot and reverse shot, the people here do not move. The video gives the illusion of taking place within a temporal density when in reality this is the frozen time of photography. Claerbout has a special penchant for this interplay between two regimes of the visible, but here it attains a new level in the deconstruction of our belief in the image. Each person was, in effect, filmed individually in a studio, then inlaid into the ‘American Room’, the trading room in an old London bank building. This actual gathering never happened. The actors never set foot in the room, and the concert, naturally, was never held there. Everything in Claerbout’s video is false, reminding viewers of the constructed nature of their experiences.

In The American Room, Claerbout films what is a very old relation to the artwork—one that, like the people it shows, is very stiff. The reception of a work at a classical concert is governed by specific codes, established from defined places, in a framework that is not only closed but also, as here, surveilled. Everything soon seems false, not only the concert itself, but also the postures, the gazes, the expressions of concentration: each person seems, above all, to be putting on a show of listening. The hairdos are impeccable: the studied expressions give an impression of self-satisfaction. The faces have a knowing air that suggests class consciousness – a feeling of cultural superiority. The concert comes across more as a social event than as an authentic pleasure. The piece designates a performative register that seems at first sight more authentic than the one offered by the photographic medium, as a sharing of a given space–time, but here emptied of its substance, so that only the codes remain. Claerbout plays on the sacralization of the performative experience, of the art of the present, and catches the viewer in the trap of their own fascination with the concert form.

David Claerbout, American Room, 2009. Installation view at Wiels, Brussels, 2011. Courtesy of the artist.

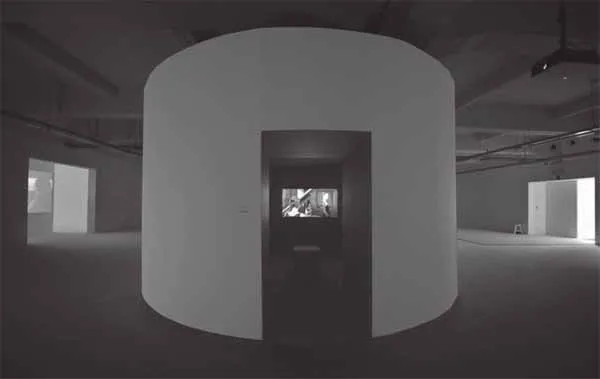

Video, as a multiple, affords viewers a moment of solitary reception; the organisation of the artistic event does not imply inclusion in a group. They come and go as they want, choose the moment and duration of their watching, without taking into account other people’s listening patterns. This modality means an avoidance of closed receptive codes. Each piece can offer its own relation to the viewer, accepting its repetitive nature while offering conditions of reception that encourage the development of an individual perception of the work. When The American Room was exhibited at the Wiels centre in Brussels, in 2011, Claerbout placed it within a fairly narrow, spherical projection area soundproofed by acoustic foam. In contrast to the extensive area in which the other installations were placed, this set-up required that viewers isolate themselves in a mental space. By showing the foam covering the walls, Claerbout made evident the artificiality of the isolation, and the sense of confinement was further emphasized by the spherical structure. All these modes of presentation indicated a type of relation to the image that all Claerbout’s work rejects. In this instance, it served simply to stigmatize the spectators represented in The American Room.

In comparison to this moment of collective sharing, which evaporates to leave only caricature expressions that are manifestly acted (faked), the other video works installed here seemed to offer the viewer experiences that were more imaginatively stimulating. The half-darkness imposed by the projection limits the impact of separation from other people’s gaze, while the temporal openness allows each spectator to determine the duration of their immersion. Instead of staying in a given pose or place, the video installation effects a critique of certain traditional, rigidified forms of theatric...