This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 162 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

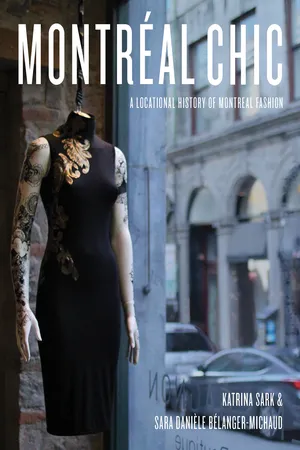

Montréal Chic

A Locational History of Montréal Fashion

About this book

Montréal is à la mode. A fashionable city in its own right, it also boasts fashion schools, an industry packed with local designers and manufacturers and a dynamic scene that exhibits local and international collections. With its vibrant cultural life and affordable cost of living, designers and artists flock from all over to be a part of Montréal's hip fashion community. MontréalChic is the first book to document this scene and how it connects with the city's design, film, music and cultural history. Scholars Katrina Sark and Sara Danièle Bélanger-Michaud are intimately acquainted with Montréal and use their firsthand knowledge of the city's fashion to explore urban culture, music, institutions, scenes and subcultures, along the way uncovering many untold stories of Montréal's fashion scene.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Montréal Chic by Katrina Sark,Sara Danièle Bélanger-Michaud, Susan Ingram in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Fashion Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

History

Chapter 1

A Locational History of Fashion in Montréal

Fashion is essential to the world of modernity,

the world of spectacle and mass-communication.

It is a kind of connective tissue of our cultural organism.

(Elizabeth Wilson)1

In the first part of our study, we focus on the history of Montréal fashion. We begin with a brief overview of the key events, designers, organizations, and developments in Montréal’s garment and fashion industries, with a particular emphasis on women’s roles and contributions, as well as the significance and legacy of this history. In her research on the Canadian garment industry, Cynthia Cooper, the curator of costume and textiles at the McCord Museum, discovered early documentation of the Montréal fashion industry in the first census of 1871,2 only four years after Canadian Confederation. In the 1850s, Gibb and Co., one of the first Montréal-based tailoring firms, started to receive orders from Canadian and American customers. Cooper found that, at the time, Québec and Ontario accounted for about 95 percent of the country’s garment production, largely due to their concentrated immigrant labour.3 From the nineteenth century on, Montréal developed and diversified its garment manufacturing. It became the fourth largest industry in Québec and peaked in the 1980s, becoming the third largest clothing manufacturing centre in North America, after New York and Los Angeles (Fig. 1.1).4 As was the case in Berlin, garment production in Montréal industrialized gradually, with the majority of the work being done by seamstresses and dressmakers in their homes. As historian Suzanne Cross explains, “in 1892, the J.W. Mackedie company employed nine hundred women in the home; the H. Shorey company, which employed only one hundred thirty women in its workshops, employed fourteen hundred women at home.”5 Because milliners and seamstresses worked mostly at home or in small workshops, they were not protected by the Québec Factories Act of 1885 and could be forced to work longer than the ten hours a day set by the act.6 Moreover, seamstresses and home workers were usually paid per item sewn, rather than an hourly wage, which meant having to work extremely long hours for little pay, and thus sewing was far from a glamorous profession.7 As Mavis Gallant put it in one of her Montreal Stories (2004), “Mme. Carette took Berthe in her arms and said she must never tell anyone their mother had left the house to sew for strangers. When she grew up, she must not refer to her mother as a seamstress, but say instead, ‘My mother was clever with her hands.’”8 Betty Guernsey, the biographer of Gaby Bernier, one of Montréal’s first couturiers, noted that “in the days between the two world wars, most families who could afford it had seamstresses who came to the home and stayed sometimes three to four weeks at a time, making clothes, mending sheets and altering maids’ uniforms.”9

Fig. 1.1: “Montréal Chic” printemps, La Patrie, March 1914 (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec).

Fig. 1.2: Clothing Factory Maurice Laniel, 7542 Rue St. Hubert, Montréal, 1941 (photo Conrad Poirier, with the permission of the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec).

Since the early days of the Industrial Revolution, the clothing manufacturing industry, described as the “sweating system,” has been a highly exploitative enterprise, especially for women who have consistently earned much less than men (Figs. 1.2 and 1.3).10 Women (mostly Jewish and French Canadian) made up 70 percent of the early workforce, and in 1893 the National Council of Women of Canada was established “for the betterment of working conditions of female factory workers,” followed by the first general strike in 1910 by Montréal garment workers protesting their working conditions, and culminating in the massive 1937 strike of 5000 Québec women that resulted in the institution of higher wages and better working conditions.11 It was not until 1919 that the Québec government introduced a minimum wage for women.12 Immigrant women, who made up 50 percent of the garment industry, had the most poorly paid and insecure jobs, and Montréal’s clothing industry largely depended on their labour.13 Mordecai Richler’s famous protagonist Duddy Kravitz, who grew up in the Jewish ghetto around Mile End and began working in his uncle’s garment factory as a teenager, is described as follows:

Duddy took his first regular job at the age of thirteen in the summer of 1945. He went to work in his Uncle Benjy’s dress factory for sixteen dollars a week, and there he sat, at the end of a long table, where twelve French-Canadian girls, wearing flowered housecoats over their dresses, sewed belts in the heat and dust. The belts were passed along to Duddy, who turned them right side out with a poker and dumped them in a cardboard carton. It was tedious work and Duddy took to reversing the black and red and orange belts in an altogether absent-minded manner.14

Fig. 1.3: Clothing Factory Maurice Laniel, women workers, Montréal, 1941 (photo Conrad Poirier, with the permission of the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec).

It was not until 1975 that the Québec Charter of Rights and Freedoms set forth the right of equal pay for work of equal value, and hundreds of women launched grievances over discrimination and injustices with the help of Action-Travail des Femmes.15 Furthermore, prior to Québec’s language laws of the 1970s, most garment manufacturing jobs were held by French-Canadian women and immigrants, while many anglophone and bilingual Montréalers had more professional options and advantages.16 In another short story by Mavis Gallant, the Carette family moves to Rue Saint-Hubert in the Plateau, which the now-grown, bilingual daughter Berthe, who works in an office, describes as in decline because “a family of foreigners were installed across the road. A seamstress had placed a sign in a ground-floor window – a sure symptom of decay.”17 Thus, Montréal’s clothing and fashion industry has always been “inextricably linked to technology and gender,” as well as to immigrant labour.18

Locationally, Montréal fashion initially originated in the Old Port, the former industrial and commercial centre of the city in the nineteenth century, and relocated north to St. Catherine Street at the end of the century with the advent of les grands magazins – Montréal’s numerous opulent department stores – and the establishment of the Golden Square Mile around Sherbrooke Street with its first fashion ateliers in the 1920s and 1930s, before finally settling further north in the garment district of Mile End, around Rue Chabanel.19 From around 1870, Montréal was the centre of the Industrial Revolution in Canada, and by the 1920s it had become the “commercial capital of Canada,” hosting the headquarters of leading banks, important financial and commercial houses, telegraph and telephone companies, as well as the railway and the steamship lines.20 The original department stores included Holt Renfrew (established in 1837), Morgan’s (1845), Jas. A. Ogilvy (1866), John Murphy and Co. (1867), Dupuis Frères (1868), Eaton’s (1869), S. Carsley (1880), and W. H. Scroggie (1883) (Fig. 1.4 Chart).21

For a long time, department stores based in urban centres such as Montréal and Toronto circulated their merchandise through mail-order catalogues, particularly from the 1920s to the 1960s. The first Eaton’s catalogue was published in 1884,22 while local fashion magazines, such as Montréal Mode (1904−1930), featured illustrations of European fashion (Fig. 1.5).23 St. Catherine Street became the main commercial destination, with the Goodwin, Murphy, and Ogilvy department stores on the west side and Dupuis Frères on the east side of the street. From its early days, Dupuis Frères’ mandate was to reflect and uphold the three pillars of French-Canadian society: nationalism, religion, and family.24 As Mavis Gallant made a point in one of her short stories, having a charge account at Dupuis Frères was considered a mark of social status.25 In 1952, a strike at Dupuis Frères mobilized 800 professional women, and “their victory, several months later, was of particular significance, as it showed that women retail workers could be mobilized against their employers, even employers who were francophone and Catholic. After the Dupuis collective agreement was signed, other Montréal department stores paid their employees better wages and improved working conditions.”26 Dupuis Frères eventually closed in 1978. Its bankruptcy was not only financial, but, as Robert Trudel found in his research, can also be linked to the social changes in French-Canadian society after the Quiet Revolution in the 1960s, with religion and the family losing their ideological stronghold and with the secularization of French schools and discontinuation of the school uniforms that the department store specialized in (Fig. 1.6).27

From the late 1800s until almost 1940, 70 percent of “the entire wealth of Canada” was reputed to live around the Golden Square Mile,28 with Sherbrooke Street as its most exclusive residential address.29 However, with the Great Depression, the Square Mile was transformed both economically and architecturally: “when the industries that built the capitalist fortunes fell silent, the grand houses were left behind and were demolished in favour of high-rises, turned into boarding houses, or bought up by institutions such as McGill University.”30 Many of the original Montréal couturiers were women, including Gaby Be...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Locating Montréal Chic

- Part 1: History

- Part 2: Spectacles

- Part 3: Innovation

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Filmography

- Back Cover