![]()

Chapter

1

Audrey Hepburn: Fashion, Fairy Tales and Transformation

Lynn Hilditch

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s in particular, Audrey Hepburn portrayed characters that underwent an identity transformation. In the case of Princess Ann, Sabrina Fairchild and Holly Golightly, for example, it was mostly self-motivated, but for others, such as Jo Stockton and Eliza Doolittle, it was an imposed transformation. Hepburn once admitted that she relied upon her costumes to help her construct her characters, rather like a little girl playing at dressing up. To her, the costuming was a crucial part of the acting process, especially as she had never had any formal acting training. Audrey explained, as quoted by Melissa Hellstern in How to be Lovely: The Audrey Hepburn Way of Life:

Clothes, per se, the costume is terribly important to me, always has been. Perhaps because I didn’t have any technique for acting when I started because I had never learned to act. I had a sort of make-believe, like children do.

Hepburn’s ability to transform her characters so easily – tackling within the same film the opposing roles of princess/lady/socialite and girl-next-door/flower girl/chauffeur’s daughter with equal conviction – is perhaps due to Hepburn having undergone her own personal off-screen identity transformation from Edda Hepburn van Heemstra, the little girl born into Dutch aristocracy in 1929 who dreamed of becoming a ballerina like her heroine Margot Fonteyn, into Audrey Hepburn, one of the most influential twentieth-century movie stars and fashion icons.

Unlike the female sex symbols of the 1950s and 1960s, such as Marilyn Monroe, Lana Turner, Jane Russell and Bridget Bardot, whose glamour and star personas appeared manufactured or contrived in order to appeal to a male audience, Hepburn was very much a ‘woman’s woman’, appealing to a female audience through her natural beauty, individual feminine style and exceptional fashion sense. Hepburn’s look of the ‘modern woman’ was partly due to her lifelong friendship with the French fashion designer Hubert de Givenchy whom she met on the set of Sabrina (Billy Wilder, 1954) in 1953 and who would design her clothes for the next forty years. Hepburn claimed, as quoted by Pamela Clarke Keogh in Audrey Style, that Givenchy’s clothes were ‘the only clothes in which I feel myself. He is far from a couturier; he is a creator of personality’. Givenchy and Hepburn collaborated on many of the costume designs for her films, creating what became known as ‘The Hepburn Style’, and although Edith Head won an Oscar for the Costume Design on Sabrina (and previously designed Hepburn’s costumes for Roman Holiday [William Wyler, 1953]), Givenchy had provided design sketches for many of the outfits worn in the film, including Sabrina’s ball gown. Therefore, it was partly due to her relationship with Givenchy, as well as the inspired use of on-screen fashion, that enabled Hepburn to create, develop and transform her characters in some of her most popular films, in particular, Roman Holiday, Sabrina, Funny Face (Stanley Donen, 1957), Breakfast at Tiffany’s (Blake Edwards, 1961) and My Fair Lady (George Cukor, 1964).

‘At midnight, I’ll turn into a pumpkin and drive away in my glass slipper’ (Anya, Roman Holiday)

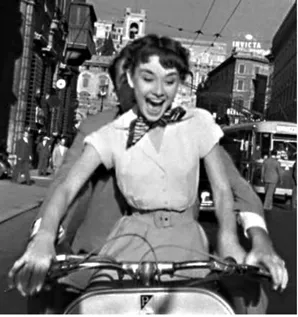

Hepburn’s first significant on-screen identity transformation was in William Wyler’s romantic comedy Roman Holiday – her first Hollywood film role. In a reversal of the ‘Cinderella’ story, Hepburn plays the young Ruritanian Princess Ann (see Figure 1) who has become tired of her role as the personification of ‘sweetness and decency’ and bored of all the endless functions, conferences and parties that she is expected to go to during her demanding goodwill tour of European cities. After attending a lavish ball thrown in her honour, the princess retires to her bedchamber where she is undressed, briefed about the next day’s duties and put to bed by the Countess Vereberg (Margaret Rawlings). However, her disillusionment with her restricted and rather old-fashioned royal lifestyle is apparent:

Fig. 1: Hepburn as the regal Princess Ann in Roman Holiday.

Princess Ann: I hate this nightgown. I hate all my nightgowns, and I hate all my underwear too.

Countess: My dear, you have lovely things.

Princess Ann: But I’m not two hundred years old. Why can’t I sleep in pyjamas?

Countess: Pyjamas?

Princess Ann: Just the top part. Did you know that there are people who sleep with absolutely nothing on at all?

Note how the nightgown in this scene closely resembles the nightwear that Hepburn would later wear in the ‘I Could Have Danced All Night’ (Frederick Loewe and Alan Jay Lerner, 1956) number in My Fair Lady as she begins her character transformation from the common flower girl to the lady (a reversal of her identity change in Roman Holiday). Hepburn’s ability to combine comedy with an element of naive charm is demonstrated when the princess gets hysterical and has to be sedated by the royal doctor. Then, in an act of anesthetized rebellion, she defies the orders of the palace and escapes into the city of Rome in the back of a truck. After falling asleep on a park bench – homeless and alone in an unfamiliar city – she is rescued from her downward identity spiral by American journalist Joe Bradley (Gregory Peck), her aristocratic identity temporarily discarded and replaced by the anonymity of an ordinary (and, at first, seemingly drunk) tourist. In another scene, this time in Joe’s apartment, the princess shows delight at escaping the constraints of her aristocratic existence – and, with it, her clothes – by innocently declaring, ‘I’ve never been alone with a man before, even with my dress on. With my dress off, it’s MOST unusual’. With this transformation comes a great sense of freedom and independence:

Fig. 2: Hepburn after her transformation into Anya/ Smitty in Roman Holiday.

Princess Ann: I could do some of the things I’ve always wanted to.

Joe Bradley: Like what?

Princess Ann: Oh, you can’t imagine. I’d do just whatever I liked all day long.

As part of her transformation, Ann adopts the enigmatic persona of Anya Smith or ‘Smitty’ who spends the night in Joe’s apartment, cuts off her hair, dresses in those much desired pyjamas, smokes cigarettes, gets into a fight on a barge, causes havoc on the streets of Rome on Joe’s scooter, and almost gets arrested by the Roman police force for her erratic driving (with Gregory Peck in Figure 2). In other words, the Princess does everything a princess is not supposed to do – and she revels in it. Costuming is again crucial as Ann undergoes a series of subtle changes to her outfit that results in the creation of Anya. First, she purchases a pair of flat sandals in the market; second, she goes into a barbers and demands that her long hair is cut off; third, she rolls up the sleeves of her semi-formal blouse to give a more casual appearance; and finally, she opens the neck of her blouse and adds a neckerchief to complete her visual transformation.

According to Ian Woodward in his book Audrey Hepburn: Fair Lady of the Screen, Hepburn once said, ‘If I’m honest I have to tell you I still read fairy tales and I like them best of all’, and Roman Holiday certainly has some fairy-tale elements such as Anya’s lost slipper at the ball, finding her ‘Prince Charming’ albeit in the form of an ‘average Joe’, and the ‘pumpkin moment’ when Anya returns to the palace to transform back into Princess Ann. However, there is no happy ending for the princess as she must lose her ‘prince’ once she returns to her royal life.

Figure 3: Hepburn as the young, lovelorn Sabrina Fairchild in Sabrina.

‘Paris is always a good idea’ (Sabrina Fairchild, Sabrina)

A year later in Billy Wilder’s comedy Sabrina, Hepburn played another modern-day Cinderella; Sabrina Fairchild, a chauffeur’s daughter, who has grown up living above the garage belonging to the wealthy Larrabee family of Long Island. Sabrina is a young, lovelorn girl who dreams of being swept off her feet by her ‘prince’ in the form of the youngest Larrabee son David (William Holden) – a three-time married playboy who has never given her a second glance. However, after being sent on a trip to Paris by her father to learn how to cook (and, hopefully, to forget David), Sabrina returns home two years later having transformed mentally and physically from the ‘scrawny little kid’ with her hair in a ponytail and wearing a girlish ‘sack-dress’ and collarless black shirt (see Figure 3) into a French- speaking, chicly dressed ‘sophisticated woman’ in a stylish dark two-piece double-breasted suit and accessorizing her stylish Parisian outfit with kitten heels, gloves, a light-coloured turban hat and bohemian-style hoop earrings (see Figure 4). She also has the ultimate French fashion accompaniment – a toy poodle (humorously named David), also exquisitely dressed in a diamante collar. In a letter written to her father a few days before returning from Paris, Sabrina demonstrates how she has considerably matured as she pronounces, ‘I have learned how to live; how to be in the world and of the world.’

Figure 4: Hepburn as the ‘sophisticated woman’ after her Parisian transformation in Sabrina.

In many of Hepburn’s films, including Funny Face, Love in the Afternoon (Billy Wilder, 1957), Charade (Stanley Donen, 1963), Paris When It Sizzles (Richard Quine, 1964), How...