eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Filming the City

Urban Documents, Design Practices and Social Criticism through the Lens

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 196 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Filming the City

Urban Documents, Design Practices and Social Criticism through the Lens

About this book

Filming the City brings together the work of filmmakers, architects, designers, video artists and media specialists to provide three distinct prisms through which to examine the medium of film in the context of the city. The book presents commentaries on particular films and their social and urban relevance, offering contemporary criticisms of both film and urbanism from conflicting perspectives, and documenting examples of how to actively use the medium of film in the design of our cities, spaces and buildings. Bringing a diverse set of contributors to the collection, editors Edward M. Clift, Mirko Guaralda and Ari Mattes offer readers a new approach to understanding the complex, multi-layered interaction of urban design and film.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Filming the City by Mirko Guaralda,Ari Mattes, Edward M. Clift, Graham Cairns in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section One

Film as Spatial Theory

Chapter 1

Unlawful Entry: The imbrication of suburban space and police repression in Jonathan Kaplan’s Los Angeles

Ari Mattes

A great metropolis today absorbs and divides the world in all its diverseness and inequality.

Marc Augé, Non-Places

Now the fat policeman wakens definitely, and feels of his club to see that it is ready for business.

Upton Sinclair, The Jungle

Motherfuck you and your punk-ass ghetto bird.

Ice Cube, Ghetto Bird

Introduction

Jonathan Kaplan’s 1979 film Over the Edge opens with an image of a signpost, perfectly framed by the screen: ‘Welcome to New Granada. Tomorrow’s city… today.’ The camera tracks back to reveal a panorama of this city of the future. Surrounding the sign is an expanse of arid, vacant lots; a poorly maintained asphalt road stretches towards a background peppered with barely visible outlines of condominiums, the putative message of the sign completely undercut by its squalid surrounds. In sync with a heavy rock guitar riff (Cheap Trick’s ‘Speak Now’), a caption rolls across the screen making explicit the connection between morally bankrupt hyper-development and urban waste; the film is based on ‘true incidents’, it informs the viewer, occurring in a community in which city planners overlooked the fact that a quarter of the population were aged 15 or under. The proliferation of sub/urban crime in the United States – such a charged political topic over the next decade – is explicitly linked to an alienation built into the very structure of habitable space. Kaplan’s SoCal is an overdeveloped wasteland, its suburbs the ‘excrescence of the circulation of capital’ (Lefebvre 2003: xvii), the poorly designed and developed SoCal ripped apart by urbanist Mike Davis in Ecology of Fear (1999 [1998]: 59–91).

The following scene in the youth centre – the first of the diegesis proper – juxtaposes this dead exterior space with the vitality of life inside the centre, a dialectic that comes to structure the film as a whole. Carl (Michael Kramer) and friends retreat to the youth centre several times throughout the film in the face of a horde of hostile property owners and developers who are bolstered by a police force whose gratification involves the harassment and intimidation of these ‘delinquents’. This youth centre, site of productive happiness, becomes the principal target of the malevolent Chief Doberman (Harry Northrup), who coerces the community into shutting it down. The teenagers are left to play amidst the ruins, forsaken, in unfinished condos and on vacant, rubble-strewn lots, trying to make the most of their containment within an at best dull, at worst virtually post-apocalyptic, suburban space. Their occasional ‘crimes’ are clearly envisioned by Kaplan as symptoms of an ennui for which the city-planners and -developers, the forces of capital that subordinate and ruthlessly reify the living environment into exchangeable ‘lots’, are entirely responsible. Over the Edge, indeed, deliberately critiques capital’s construction and militarization of urban space as a means of control.

Figure 1. Over the Edge (1979), © Orion Pictures.

This creation of cadastral space in tandem with (and facilitating) police manipulation and repression becomes the central thematic in Kaplan’s later masterpiece, Unlawful Entry (1992), the focal point of this chapter.

The genius of Unlawful Entry lies in its analysis of police repression as intertwined with the urban geography of Los Angeles itself – in its exploration and critique of Los Angeles as a city constructed in part to facilitate surveillance for the advantage of the state–corporate nexus. The film offers a critique of contemporary methods of police surveillance, à la Zygmunt Bauman and David Lyon’s discussion in Liquid Surveillance (2013) and Paul Virilio’s La machine de vision/The Vision Machine (1994 [1988]), displaying a profound suspicion of all forms of police surveillance, and, more so, the grid-like demarcation of cadastral space in Los Angeles that enables such diffuse and seamless surveillance. Los Angeles is envisioned by Kaplan as Mike Davis’s ‘fortress’ from City of Quartz (2006 [1990]: 221–63) – a constellation of walls and passages cordoning off space as a means to create, categorize, monitor and channel vectors of criminality. Kaplan’s all-seeing camera becomes homologous with the sweeping, repressive motion of the surveillance (and assault) drones that would become globally notorious less than a decade after the film was made. Los Angeles, thus, is no longer envisioned as the electric sprawl of Jean Baudrillard’s Amérique/America (1988 [1986]: 52–55), but, rather, as a carefully orchestrated arena enabling all-pervasive state surveillance.

In the context of a great deal of futuristic techno-babble regarding the contemporary urban aesthetics (and ethics) of Los Angeles – both apocalyptic and celebratory alike – Unlawful Entry serves as a reminder that, as David Harvey eloquently points out in The Enigma of Capital (2010), design in and of the city usually serves the interests of property developers (enforced by policing) above and beyond the interests of its inhabitants.

Unlawful Entry

The narrative of Unlawful Entry follows a mid-thirties couple, Karen Carr (Madeleine Stowe) and her property-developer husband Michael (Kurt Russell), who live in Los Angeles in one of the white-barricaded suburbs dissected by Mike Davis in City of Quartz (2006 [1990]: 151–219). Their house is broken into by an African American burglar in the opening scene, and in response to this break-in they develop a relationship – commercial and personal – with police officer Pete Davis (Ray Liotta). They contract him to install a new security system, and Michael hires him to plan security for a nightclub he is developing. When Officer Davis captures the suspect and beats him in front of Michael as part of a perverse male friendship ritual – a ‘show’ of brotherhood through violence, sickeningly recalling the racist history of LA and the LAPD (Davis 2006 [1990]: 267–322; Davis 1999 [1998]: 410–11) (and, of course, the Rodney King beating, occurring fifteen months before the film was released – ‘Have you got a home video? Nowdays, you’ve gotta have a video,’ a police officer jokes to Michael when he reports Officer Davis’s harassment) – Michael decides it would be best to have nothing more to do with Davis. In response to Michael’s (and eventually Karen’s) rejection, Davis proceeds to stalk, harass, intimidate, illegally survey and physically attack the couple. This escalates into a life and death struggle in the final sequences of the film, with Karen and Michael killing Officer Davis.

The film is ostensibly in the mould of the suburban paranoia thrillers of the 1980s and early 1990s: Fatal Attraction (Lyne, 1987); The Hider in the House (Patrick, 1989); The Hand that Rocks the Cradle (Hanson, 1992). An evil outsider penetrates the sanctity of domestic space and is violently expurgated by the end of the film; the alien ‘intruder’, in the case of Unlawful Entry, just happens to be a cop.

However, from the opening sequence Kaplan explicitly ties this violence to urban design and ‘ghettoization’. Crime and criminality are depicted as systemic products, the direct residue of a hostile, alienating urban experience that is necessarily facilitated by big capital and a repressive police force; Los Angeles is envisioned by Kaplan as a panoptic city designed to facilitate covert and overt police surveillance, repression and manipulation.

Figure 2. Unlawful Entry (1992), © Largo Entertainment and JVC.

As the opening credits roll, the sound of a helicopter ushers in vision from above – presumably the point of view of one of the LAPD’s infamous ‘ghetto birds’ – looking down upon a dead body. The corpse is surrounded by police, guns drawn; and police cars, lights flashing. The image is grey, washed out, the site some kind of abandoned concrete lot on the side of a freeway: Los Angeles as post-industrial wasteland. The sweeping, drone-like camera follows one of the police cars, accompanied by James Horner’s melancholic, jazzy score, as it leaves the crime scene and accelerates down the freeway. The camera tracks across the river-made-concrete – a necessary landmark in every modern LA film – and up to a wide panorama of downtown, its skyscrapers obscured in a smoggy haze. The corpse of the opening image is directly linked to the urban at large, envisioned as a product of urban degradation – LA is imagined as a corpse of a city.

Figure 3. Unlawful Entry (1992), © Largo Entertainment and JVC.

The film then cross-fades to a helicopter shot over one of the city’s myriad suburbs. The bright blue of several pools – the pool, as a symbol of affluent middle-class suburbanity, becomes a critical topos as Unlawful Entry unfolds – breaks up the drab grey of the buildings crowding the rest of the image. A figure – a woman – is swimming laps in one of the pools, and there is something acutely voyeuristic at play as the camera homes in on this solitary swimmer, oblivious to this (the viewer’s) eye in the sky.1 Noises typically associated with the suburban seep into the soundtrack: birds, children playing, harmless chatter. This juxtaposition of the city skyline and the suburbs, in their sprawling and monotonous, grid-like arrangement, clearly invokes the discourse of many 1980s Reagan-era suburban-paranoia films, in which the urban is seen as a cesspool of crime in contrast with an immeasurably ‘cleaner’ suburbia.

The film cross-fades again to a sunwashed, street-level shot of a classic Los Angeles suburban home, stucco, Spanish and palm-tree bound, a product of the imaginary deftly analysed by Carey McWilliams in the 1940s in Southern California: An Island on the Land (2010 [1946]). The image fades into night – the streetlamp is now on, and light from a TV flickers in an upstairs window. To cap off this constellation of Brady-esque suburbanalia, a man walking a barking dog crosses the image, left to right. This is the LA suburb in all its abysmal glory: more banal and less ‘old money’ than the Chicago suburbs lampooned in Risky Business (Brickman, 1983) and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (Hughes, 1986), the antithesis of the New York neighbourhoods of Spike Lee and Woody Allen with their eclectic, electric mix of cultures.

Figure 4. Unlawful Entry (1992), © Largo Entertainment and JVC.

The film cuts to a bedroom inside the house; playing on the television is a talk-show interview – a female subject is engaged in a discussion about her childhood, formerly private memories now public. Our attention is deliberately focused on watching by the homology between the opening police chopper and our own eye as cinematic spectator – between a paramilitarized brand of surveillance and our own scopophilic activity, recalling Virilio’s argument in Guerre et cinéma/War and Cinema (1989 [1984]) regarding the symbiosis between military strategy and cinematic spectatorship – and then intensified by this seamless passage into the private domain of the bedroom: the chapel, so to speak, of domestic space. As though in complicity with this veiled critique of televisual (and surveillance) culture, the camera moves through the bedroom to rest on photos of our two stars, as yet unintroduced in the diegesis.

The camera then tracks, with undeniable eroticism, across a bare female leg, sticking out amidst rumpled sheets. It rests on the as-yet-unintroduced Karen Carr, asleep. There is a clanging noise off camera (the burglar) and her eyes open, coming into consciousness within the frame of the narrative in parallel with the intrusion of the burglar, as though her recognition that an intrusion – an ‘unlawful entry’ – has taken place is equally directed at the viewer, at our own intrusion into her home.

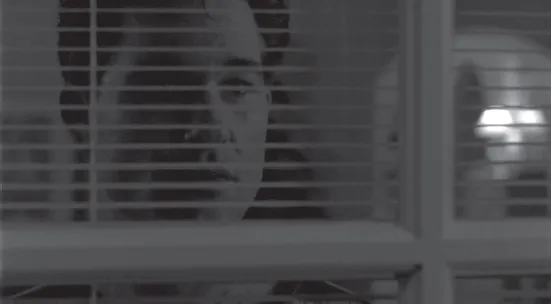

Figure 5. Unlawful Entry (1992), © Largo Entertainment and JVC.

She alerts husband, Michael, who heads off to investigate. He checks the myriad rooms of their house before pausing at the window and looking out at the street. As the camera cuts to the exterior, photographing his anxious eyes, blinds cutting across his face, it becomes exquisitely clear to the viewer that Michael is trapped within a self-made prison. He is the epitome, in this moment, of the paranoia – a paranoia that imprisons – of life in the surveillance age, of the white-suburban paranoia that classes the black and the urban as evil Other. The opening invasion sequence culminates, moments later, with this paranoia-made-true – the intruder attacks Michael, grabbing Karen as a hostage and holding one of their kitchen knives to her throat, before fleeing and leaving her in the pool, unharmed.

It is worth noting that the weapon, the knife, comes from the Carrs’ house itself, given the connection Kaplan makes (and emphasizes as the film progresses) between suburban segregation, virtual gatedness, and urban degradation and deprivation. This crime is, if not created, then at least exacerbated, by the technologies and tools of the affluent. Furthermore, the scene immediately following this intrusion begins with an extreme close-up of a police car, its caption ‘to serve and to protect’ clearly legible in the upper-right corner of the frame. Given this ability ‘to serve and protect’ has already been called into question in the opening image of the film – police standing around a dead body – and given that the viewer’s uneasiness is only amplified by the homology drawn between police surveillance and cinematic intrusion – it is only natural that this image should assume a particularly grim hue at this point, gesturing towards the savage violence against Karen and Michael to come, courtesy of the LAPD.

The imbrication of urban design and police repression

Thus, Kaplan’s opening sequence draws the viewer’s attention to the air-vision layout of LA, its horizontal design facilitating rampant police surveillance, presaging the ‘droneism’ that would come to full maturation in the twenty-first century,2 and reflecting on the computerization and digitization of daily life so provocatively theorized by Baudrillard in L’échange symbolique et la mort/Symbolic Exchange and Death (1993 [1976]) and by McKenzie Wark in Gamer Theory (2007). Kaplan’s presentation of the city’s spatiality recalls David Harvey’s critique of Hausmann’s redevelopment of Paris in Rebel Cities: ‘[Hausmann] created an urban form where it was believed […] sufficient levels of surveillance and...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Section One: Film as Spatial Theory

- Section Two: Film as Spatial Research and Experiment

- Section Three: Film as Spatial Practice

- Epilogue

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

- BackCover