![]()

1

ART IN THE PRIMARY SCHOOL: TOWARDS FIRST PRINCIPLES

Geoffrey W. Southworth

Vol 1, No 2, 1982

Art in the curriculum

The English primary school curriculum is made up of a variety of subjects and activities. The range of the curriculum is diverse, but not all the subjects are equal since the tradition of the three Rs creates an elite core of the so-called ‘basic subjects’–reading, writing and number. One can appreciate the reasons for emphasizing these skills but one has less enthusiasm for the damage which this hierarchy tends to inflict on the other activities. Maths and English, generally speaking, have become the titans of the primary curriculum, towering over all other subjects. Moreover, they dominate the attitudes and assumptions of primary curriculum development.

Art is usually one of the activities associated with primary schooling. In one sense it is true to say that it is no longer necessary to fight for art’s inclusion in the curriculum. In another sense, though, this is not true. Because of the pre-eminence of maths and basic language skills, art, along with certain other subjects, has tended to suffer. For one thing it is the misfortune of primary art to be considered as simply a decorative frill to the other so-called more important areas of the curriculum. Art is regarded as an occupation which interests children, keeps them busy and is sometimes mildly therapeutic. However, compared to the main purpose of primary schooling, which is the transmission of basic skills, art is ‘non serious’. Art, it is thought, has nothing whatsoever to do with mathematical and linguistic understanding. Indeed, art is often considered to have only one main function, namely, to provide opportunities for children to express themselves. Thus, once art is pigeonholed as ‘expression’ it becomes typical of such compartmentalizing to regard art as having no intellectual function at all. Art may be ‘in’ the curriculum but primary art is not given much respect when placed alongside certain ‘more important’ activities. Art is under-emphasized and it is under-estimated.

The 1978 HMI primary survey said that the general progress of children and their competence in the basic skills appear to benefit where they are involved in a programme of activities that include art, crafts, music, P.E., science, history and geography as well as language, mathematics and religious and moral education (DES 1978: 114, para. 8.29). Insofar as art is concerned we still have to demonstrate the validity of this claim. Primary art specialists need to challenge the attitudes of many of our colleagues in order to reverse the prevailing prejudices which result in art’s low standing and diminish and restrict its purpose. Those concerned about primary art need to become more active and convince more teachers of art’s real contribution to the child’s development. To do this we need to have a fairly clear conception as to the nature of the activity we call art. Only then can we begin to justify the role and scope of art education.

Art’s contribution to the child’s development

In attempting to identify the nature of the activity we call art it is necessary to ask: what is art’s unique contribution to the education of children? Eisner’s response is to say that:

The prime value of the arts in education lies in the unique contributions it makes to the individual’s experience with and understanding of the world. The visual arts deal with an aspect of human consciousness that no other field touches on; the aesthetic contemplation of visual form. (Eisner 1972: 9)

Eisner demonstrates that the fundamental nature of the activity is concerned with visual form and this is widely accepted by the common use of art’s alternative title, namely visual education. However, Eisner’s statement also suggests certain other aspects of art education. For one thing it is noted that art involves the individual’s experience with the world. Art education is implicitly concerned with individuals and a regard for individuality. Another thing which is embodied in Eisner’s thinking is the notion that the visual arts deal with an aspect of human consciousness. This suggests that consciousness is comprised of a number of aspects that consciousness is not singular or monolithic but, rather, that it is broad and made up of a variety of areas of awareness. Such a view is supported by Hirst’s idea of forms of knowledge (Hirst 1974).

It is therefore possible to say that Eisner raises three areas of attention: (1) the visual aspect of art education; (2) individuality; (3) human consciousness. Each makes significant contributions to the nature and role of art education and each needs to be examined.

The visual aspect

As human beings we have a variety of symbol systems at our disposal and in some way or another each of these systems is a mode of understanding. Art is primarily a visual mode, although this is not to deny that there are tactile elements as well. As a visual mode, art can be thought of as a visual ‘language’ and in order that children can come to know this visual language, they need to know the syntax of it. They need to know the syntax of line, colour, shape, space, texture, and so on. This is achieved through looking, which is part of the process of seeing. Teachers need to teach children to see. As teachers our task is similar to that identified by the novelist Joseph Conrad, who once said that through his writing he was hoping to make the reader hear and to feel and, before all else, to see. That and nothing else was his task and, as he so pertinently added, it was everything (Conrad The Nigger and the Narcissus [1897] 1989: 13). The only difference for art educators is to achieve seeing and feeling through the spoken word and via the power of the visual image rather than the written word. It is in this sense that we are all visual educators.

Children need to be taught to observe and investigate the visual world and record and express their ‘findings’ in visual terms. This is why drawing is so important. Drawing is the process that leads the eyes to see, since for the artist drawing is discovery. It is a platitude in the teaching of drawing that the heart of the matter lies in the specific process of looking. A line is not only important because it records what you have seen but because of what it will lead you on to see (Berger 1960: 23). As the painter Bridget Riley has said, we work from what we know towards what we do not know.

Yet to speak about teaching children to look fails to convey the dynamics of the process. Looking can and should, at various times, involve interest, curiosity, awe, wonder, analysis, discussion, recording, sharing, tactile experience, expression and so on. These are but a few of the many words appropriate to looking and seeing. As such, these words suggest that looking and seeing are closely connected with (i) observation, (ii) investigation, (iii) communication; three activities which surely are the cornerstones of education. That in itself ought to be sufficient justification for art education. Through the process of seeing and the learning of a visual language, art makes significant contributions to the child’s ability to observe, investigate and communicate. However, there are certain other issues which should be highlighted.

Firstly, despite the fact that visual perception plays a significant part in the learning process, the majority of schools, usually once the children attain the age of seven, ignore visual perception and in fact most other sensory modes of learning. Children are not allowed ‘to see’; they are told or shown in ways which are so neutralizing that they bear little relation to true sensory experiences. Those schools which are so lobotomized by the clamour to teach ‘the basics’ are guilty of forgetting the self evident truth that ‘seeing comes before words, the baby looks before it speaks’ (Berger 1972; 7). Seeing is not a frill, it is not peripheral, it is CENTRAL. To ignore the visual world and the language of vision is to disregard an important area of knowledge.

It is, of course, quite true that seeing in this sense is not the sole preserve of art education. Certain other subjects draw upon the world as a resource – notably the natural sciences. What art does is utilize the visual world and the senses, particularly, visual perception, for the education of artistic vision and this is the second issue. In teaching the language of vision it is our specific task to provide the child with a vision of art. We are not just dealing with perception; we are trying to teach visual aesthetic perception. Art education should try to keep the way open for the child to develop his own powers of representing reality but at the same time teach him the language well enough to be able to communicate intelligently and imaginatively with it. We should aim to teach visual art as a quality of response to visual ideas and this involves the development of visual intelligence and imagination. Our first aim should be to teach the child to look, which is to observe; to see which is to understand; and to make, which is to transform (Landor 1973).

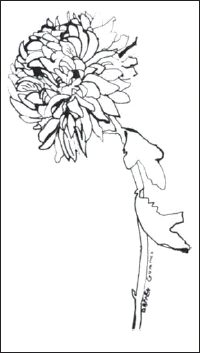

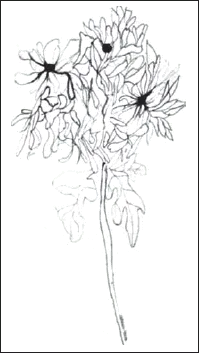

Figures 1 and 2: Visual analysis: drawings in 4B pencil by fourth-year Juniors.

Figures 3 and 4: Visual analysis: drawings in pen and ink by fourth-year Juniors.

The visual arts deal with an aspect of human life that no other area does: the aesthetic contemplation of visual form. This must be the central point for art education and, in order to teach children about this aspect of life, art education must initiate children into what it feels like to move over and about in a painting; to travel around and in between the masses of a sculpture; what it is like and what it means to produce a set of drawings, or a collage, or a piece of pottery, or an embroidered motif. Aesthetic insight, feeling from the inside what art really is, must be the central starting and expanding point for everything else (Reid 1969: 302).

A third issue to be emphasized from this consideration of the visual component is that the inclusion of visual perception provides a set of credentials which legitimate art as an intellectual activity. There are enough philosophical treatises on the place of perception and its relationship to knowledge to support this view. Equally, the psychology of perception provides further evidence to bolster this claim.1 In the long term, aesthetic perception challenges us to set aside our preferences. Attitudes and prejudices need to be set aside or suspended in order to appreciate a painting. Such attitudinal suspension is far from being easy; it is difficult and it involves thought and reason. Aesthetic vision is an active concern of the mind. Art, either as making or as appreciation, IS an intellectual activity in its own special way.

Individuality and identity

Earlier it was said that art education is concerned with individuals and a regard for individuality. As Gombrich has said; ‘there really is no such thing as art. There are only artists’ (Gombrich 1978: 4). Put into an educational context, this statement means that art should ensure opportunities for the child to be himself whilst learning about others and other things. If the child is not being himself then what he is doing may not be art, since the essence of the artist is his uniqueness and no two children are alike (DES 1959: 221). Art should attempt to embrace the individual’s contribution since that is the special feature of all expressive work whereby the teacher is presented, from time to time, with work which the pupil has produced and which the teacher recognizes that he himself could neither have visualised nor executed (Cross 1976: 36).

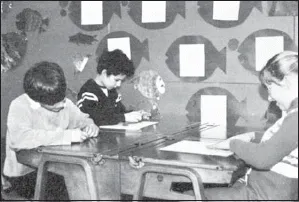

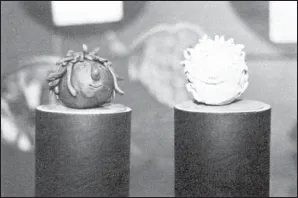

Figure 5: Third-year Juniors modelling.

Figure 6: Plasticine heads by third-year Juniors.

Individuality is focused upon for three reasons. First, because individuality is intrinsic to the artistic process. The above remarks go some way to illustrating this. Second, because individuality needs to be clarified because in practice, some schools appear to misunderstand the concept. Schools interpret individuality as to do with development and maturation; that is, schools make allowance only for individual RATES of progress. Reading schemes, maths schemes such as SMP and materials such as SRA are materialistic expressions of this emphasis. However, individuality is not just concerned with rate, it is to do with IDENTITY, with each person’s personality traits and qualities, with experiential understanding, social realities, forms of expression, and so on. Or, stated another way, visual art (along with ...