![]()

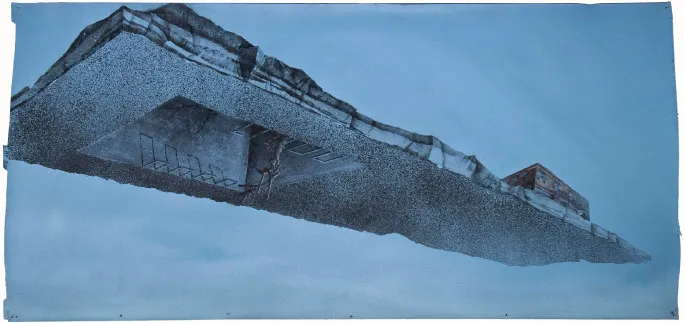

EDGAR ARCENEAUX

Edgar Arceneaux

Blind Pig #3

72"x168"

Acrylic, graphite on paper

2010

Courtesy of the artist and Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects

Photography by Robert Wedemeyer

When my daughter Zora was born in 2006, I began to have the nightmares from my childhood again. The specific fears surrounded the dark and dangerous Shadow Man. As the middle child of six, I found myself in the unenviable position of sleeping in a full bed with my two younger brothers. This meant it was incumbent upon me to protect my littlest brother from the Shadow Man by placing him in the middle spot in the bed. This left me dangerously exposed on the far edges of the bed to the worst fear of my young imagination—being snatched into the darkness.

There were other things to worry about as a kid as well. I grew up in South Central Los Angeles in a big house with lots of young families in the neighborhood. Playing with the kids from my neighborhood was fine, but the older kids from the junior high at the corner, that was another story. It wouldn’t be long before many of these kids, the very ones we grew up with, would become part of the gangs that populated the area.

Before all that, while we were a family having fun, I thought the worst thing was the Shadow Man. There are two generations of kids in the Arceneaux family. I’m the fourth of six children and I was always a little different from the rest. I had three older siblings who I could learn from, but I was also the oldest of the younger children. My knowledge that power can be a fleeting thing started at a young age. Being somewhere in between having authority and at the mercy of the older siblings is probably the foundation of my political awareness.

For as long as I could remember, my mother would tell us stories of how great a man my grandfather Edgar was. He lived in our home after my grandma died, so my three older siblings got to relish in his presence, being spoiled by him daily. They’d recall how life changed when he died, retelling so many stories of him that it produced an absence in my life, a dense fog that only imagination could attempt to fill. From my mother’s stories, I began to conjure glimpses of my worldview that were forming well before I was born.

Edgar Young migrated from Greenville, Mississippi to Los Angeles in the 1920s for a better life. He was part of that first great wave of migrants who fled the southern US to escape the institutionalized dangers of Jim Crow laws. (My family would later be part of the great exodus of Blacks out of Los Angeles in the 1980s, but that’s later in the story.) He was able to marry, purchase a home, raise five children, and was a self-taught painter and inventor. He did all of this with only a fifth-grade education—something almost impossible to do in Los Angeles today. Before trash trucks, city employees like my grandfather would push a broom and waste can on wheels, cleaning the neighborhood streets. His story, in many ways, has formed the foundation of my interests.

As I grew older, people would tell me that I looked like my grandfather. Not only that, but that I walked like him, talked like him, had a similar sense of humor. We both loved working with our hands, and we loved making art. I grew up looking at his paintings on our walls, wondering what could have made us so similar. I was searching for a definitive answer, but instead encountered a paradox. Could I be him? If so, how can I be myself at the same time?

Eventually, the gangs and drugs ran us out of the neighborhood we loved and out into West Covina, a rural community in the San Gabriel Valley. We had a nice house and great neighbors, but we were one of only two black families in what was now our new home. The year was 1984. I was 11 going on 12, and the particular area we found ourselves in was going through tremendous growth. My parents could only afford to send one of us to Catholic school, so the youngest three had our first introduction to public education. But it was good in many ways; most important was that it was safe. That meant we could ride our bikes everywhere. And we did.

All of my new friends were roughneck outcasts who came from troubled homes. We had the greatest adventures, because they had no curfews, but they also had no parents to speak of. The group of us, about eight in total, remained close through high school and into college. West Covina is just far enough away from Los Angeles to seem like a different universe, but the same cycles of loss, financial hardship and family discord were present there, too. But all the victims of it that I knew in West Covina were white. I didn’t have any white friends before this, and they didn’t have any black friends before me. My attributing whiteness with wealth, something I learned from TV, was upended.

Less than ten years after moving there, it would also be on TV that I would see Los Angeles go up in flames during the 1992 Uprising. Our house sat up on a small hill, where we could see the unnatural fog of smoke plumes consume the city during those six days. This uprising, like its predecessor, the Watts Rebellion of 1965, tore open the contradictions in the American Dream that my grandparents fled from the South to find, that my parents taught us to believe in, and that my siblings and I dutifully pursued. In the aftermath, I needed to be involved in the rebuilding of Los Angeles somehow but was uncertain as to how. What role could an artist play, and what could art do that other approaches could not? I set out, determined to figure out how.

Two years later, I was living in Pasadena as a full-time student at Art Center College of Design (ACCD). I was getting this amazing education, with access to unbelievable resources, but I constantly sought opportunities to learn and meet new mentors outside of school. I felt a strong desire to teach, but the school wouldn’t allow me to as a first-year student. It was a chance meeting, though, that led me back to South LA, just a few miles from the neighborhood I grew up in. I joined the “Art on Saturday” program as a volunteer, to teach everything that I was learning at ACCD, for free, to youth from across the city. I was initially invited by “Art on Saturday” founder and graphic designer George Evans to come check out the old fire house building they were in, and I wound up staying there for more than three years.

I could have never predicted that the beginning of my entire art career would be a succession of events from the time I was teaching at the Fire Station on Hobart Street and attending ACCD. In this confluence of moving across this spectrum of communities, I came to know artists and thinkers like John Outterbridge, Rick Lowe, Eugenia Butler, and Charles Gaines. The circles of influence expanded to institutions that merge art, design, and community-building, like St Elmo’s Village, Tricia Wards’ Culabra Art Park in Highland Park, Project Row Houses in Houston, and Sci-Arc (Southern California Institute of Architecture). I got my first paid teaching job because of the experience I gained volunteer-teaching on Hobart St. Because of the work I did at the Museum of Contemporary Art, LA in the groundbreaking exhibition Uncommon Sense, in 1997, a German collector saw my photos in the catalogue and invited me to a residency in Aachen, Germany. This led to several long-lasting relationships with curators, galleries, museums, and artists across Europe that last to this day. Reaching outside of my relationships in school, I followed my passion to give back somehow, not suspecting that I would be introduced to the great influencers of my practice, philosophy, and life.

It was Charles Gaines who was the first artist that I met who was interested in the same type of questions that inspired me. He offered both a philosophical and aesthetic language that critiqued power and explored representation that did not rely upon the conventions of figurative painting. He helped me understand that duality was a trap that could produce faulty pictures of the world, linking identity not to what something is, but to what it isn’t. I am black as long as you are convinced that you are white, to paraphrase James Baldwin.

Recognizing the contributions of my peers and mentors, I needed to build a path for my own work that would contribute to the discourse with artwork and ideas I felt were needed. The communities I was a part of and the subjects I was attracted to were often exclusionary of each other, so how could I make work that could engage with them all?

During my last term at Art Center, anger and disappointment followed my encountering illustration students having job interviews in the art office. Seemed like, every nine weeks, the entire school would rally around transportation designers giving presentations for jobs to major auto manufacturers. Deducing that all the other majors had job placement opportunities as well, it seemed unjust that we ART students were left to sink or swim with the very same student debts. I used to sell shoes, games, and rifles at Big 5 Sporting Goods in West Covina, before starting my degree at Art Center. This was the worst of the Big 5 stores in the region, but it was better than working at McDonald’s, which was my first job. (It was not nearly as much fun as my summer gig, though, playing a zombie prisoner at Knott’s Berry Farms, Halloween Haunt theme park.) It was honest work, but I promised myself that I would never go back to those jobs again. After five months of borrowing from my parents, taking freelance gigs, paying rent late, and scraping by where I could, I applied for welfare.

Standing in the unemployment line had a grim irony. I went from public college to private school to public subsidy in just four years. My first adult engagement with the social safety net would be a formative experience in life. I couldn’t go to the bank, because my account was overdrawn with late fees, so when I got my first payment, I went to the check-cashing store near my barbershop. The long lines were filled with working-class people like myself, students, moms and dads, immigrants wiring money back to Mexico, the elderly, disabled, and a mix of down and outs. Along with money, you’d get food stamps for the supermarket. I was both excited to have some cash for groceries and also wondered if those other black folks who chose to major in law and medicine were wiser than I had first suspected. Standing in the check-out line, I looked around me, embarrassed, fearing the social stagnation people project towards the needy. Then, my earliest memories of relying on the government merged with my current situation. Having five brothers and sisters, when my father was out of work, my mother shopped with food stamps. As a kid, I wasn’t sure what that strange looking money was but knew we were fortunate to have it. “Oh yeah,” I thought. “We’ve been here before and… I’m doing okay.” This just wasn’t the start I foresaw, being the first in my family to graduate from college.

With no job in sight, I was going to take advantage of the time and make a complete body of work using a process of my own creation. At that time, in 1997, one of the main issues I had with my education was how I was asked to articulate a clear picture of my project first, before I had made it. I felt that, when you place ideas so squarely into words, it cuts the edges off their amorphous nature. I wanted to make a body of work that would carve itself out through time, where the process would determine the outcome. I continued to push my drawings further, from the page to immersive, room-sized installations where people could participate in my explorations along with me.

Markets work by turning culture into reproducible units, so I knew being pigeonholed into a given style or look would doom me. So, early on, I strove to build a practice that would allow me the flexibility to make whatever I wanted and become whatever that project needed me to be. Part strategy and part recognition of a personal need for change, this path led me to a very diverse practice. Artist, draftsman, installation artist, community developer, filmmaker, theater director, researcher, author, teacher, and mentor. These are the many different disciplines that I could be working in at any given moment, but I could never do all of this alone. I show with some great commercial galleries and consider Susanne Vielmetter, my Los Angeles gallerist, as family. We’ve both grown and expanded together over the 14 years we’ve been partners, and she supports my various efforts, many of which she cannot sell. We don’t always agree, but she believes in me, and the feeling is mutual. She does remind me that she is a commercial gallery when we do a show. There need to be things that can make money. She doesn’t tell me what to make and respects my process—though at times, it can drive her crazy.

There is no balance to be found between commercial and non-commercial interests for me. It’s a conflicted ebb and flow, with deep peaks and valleys, where at times opportunities can be rich and other times not. I am never certain what’s coming; that can be exciting for some and make others flee the field entirely.

The concern that, “if I changed my work, I might lose my supporters” wasn’t entirely unfounded. The exchange was that these varied approaches to art-making enabled me to see new pictures and potentials where I might not have seen them otherwise. How far could I take this? I debated: “Could it work in Watts? Could I take this way of making art and apply it to Watts House Project?”

I visited the Watts Towers for the first time in 1996, which I hesitate to confess, having grown up only seven miles away from them. In elementary school, I learned about Simon Rodia, the Italian immigrant who built these spiraling Towers in his backyard. But like many Angelenos, I never made the journey to see them in person. As a kid, I imagined they were the size of the Eiffel Tower; they appeared larger in my memory, because most photos exclude the houses around them. This bit of editing makes the Towers appear framed by ideal blue sky and denies that they are in a historically poor neighborhood. Erasure of the homes from the frame is a subtle statement that the families and their traditions did not matter.

The Watts Towers are on a triangular lot carved by the Pacific Electric Railroad. Rodia would use the train tracks as a tool to build his masterpiece. Standing nearly 100 feet tall, they were begun in 1933, and Rodia walked away from them in 1954. Rodia had a grand ambition, and it was to build monuments that stand as a testament to the will of the individual. During the 33 years he built the towers, jazz legend Charles Mingus walked by them to school, and he would describe how some towers went up and some came down, and it was always a work in progress.

I met artist Rick Lowe by chance in 1996, when I was visiting my mentor, John Outterbridge, in his studio. Rick was invited to Los Angeles as part of show called Uncommon Sense at MOCA Los Angeles. The theme of the exhibition was social engagement—work that existed between exhibition and social service. Rick was going around the city, meeting artists and inviting them to participate in this project he was trying to do. I knew this was the connection I had been looking for and told him I’d love to be involved. I cannot recall if the project had a name at that point, but I jumped in with both feet, believing it would deepen my efforts to do something to rebuild the city after the ’92 LA Uprising.

I became Rick’s on-the-ground person in Watts, running errands, fielding meetings, passing out flyers, and acquiring the confidence to make personal connections with strangers around an idea. This is when the first vision for Watts House Project (WHP) was conceived, on the city-side of the street. The Watts Tower Art Center was built to support and preserve the Watts Towers by being a hub for the surrounding neighborhood, and it had been there since the mid-1960s. The art center had had an ambition to start an artist-in-residence by its founding director Noah Purifoy and, later, by John Outterbridge. The residency idea never fully took root, so Rick was attempting to renew the effort. Working on city property in LA can be a bureaucratic trap for artists and left the project’s wheels spinning in the mud for more than two years. That, combined with a renovation plan that was too expensive to build, and the project stalled. Though I was focused on WHP, I was still making my drawings, which allowed me to do two artist residencies, at Project Row Houses in Houston, Texas and at the Banff Center for the Arts in Alberta, Canada. It was during this time period that I began putting my thinking into writing about the tensions and connections between drawing and socially engaged art. At that time, I wasn’t able to find any synthesis between the two endeavors, other than the obvious fact that I was doing them both.

Over those first three years of WHP, from 1997 to 1999, we had visioning meetings with residents from the neighborhood about what changes they’d like to see on the block. But this was Watts. They had been at this party before—in fact, they’d been at the party for over 30 years and had been promised things repeatedly. Since the 1965 Watts Rebellion, the City of Los Angeles had promised, without much action, economic, educational, and entertainment reinvestment in the area.

I took over as director of WHP in 1999. The dual role of project director in both LA and Houston proved too much for Rick to manage. Project Row Houses, the model which inspired WHP, was beginning to expand exponentially, and Rick was never able to build the traction in LA that his plan needed to take root. There was a small amount of money left over from his efforts, and over the phone he said to me, “Do something with it.” So, I did. I began by shifting the focus of the project away from the city-side of the street and towards the families.

The Towers have always found advocates and protectors among artists, architects, and activists, yet the Towers’ improvements present a stark contrast to the neglected homes that surround them. If the Towers are what Simon Rodia could do as an individual, imagine what great things we could do as team.

Our first project was going to be with the Madrigal family, one of the most beloved families in the area. Felix Madrigal would tell me stories about how he and his family would get parking tickets in their own driveway, because it was unpaved and made of dirt. He couldn’t park in the street overnight, so they would get tickets, accumulating up to a $1000 in penalties per year. So, we worked on the drawings for a new driveway together; Felix graded the soil and hired a group of his friends to lay the concrete. In three days, we had a new driveway, at a third of the time and a third of the cost. Afterwards, we all celebrated with carne asade BBQ and cerveza to thank everyone for their beautiful work. With that small amount of funds, we now had a team, and organically, like that, our process began spilling over the fence to other houses. Genaro and Rosario Alvarez lived two houses down, and, unlike Felix, they did not own their home. When I met Genaro, he already had an idea for a project: a new fence with a radial sunburst motif. We had a brief planning meeting, and the next day, we went out and bought the materials. Three days later, I came back and half the fence was built. I said, “Genaro, I didn’t know you knew how to weld.”

“I don’t” he responded. “I taught myself how to do it.”

For a project like WHP to work, it required four things to take root: it had to extend from the values that already existed in the neighborhood; an individual or family had to vouch for it; it needed some institutional support; and, if possible, be in a location that people recognize, like the Watts Towers. The team was growing with each project, but the funds were beginning to run out. After Rick departed from WHP, there was no passing of the torch, no walking down the street and letting folks know I was taking over the efforts, like Felix had done for me when we did our first project together. Tensions between WHP with the Watts Towers Art Center had begun but wouldn’t come to critical mass for another decade. I wasn’t exactly certain why, and no one would explain it to me. That would happen much later, after it was too late to reconcile. I was young and focused on the getting the work done at the expense of political strategy, not really taking in the gravity of how those 30 years of unrealized promises from the city had left people raw and wary of anyone’s promises. With the Watts Towers Art Center unwilling to help us, having limited resources of its own, I reached out to a local landlord I met in hopes of finding some support to keep working in the neighborhood. It would be the last project for another eight years.

I chose not to be paid for the work I did with WHP. It was important to me that all the money I raised was going directly back to the families and the neighborhood. So, to support myself, I had a part-time job teaching, and I continued making my drawings and getting into higher profile exhibitions. My girlfriend Sascha and I were soon to be married, and this allowed for me to get health insurance through her job and expand our income base. This level of security was transformative, as I could take greater risks with my work with...