eBook - ePub

Cartographies of Culture

New Geographies of Welsh Writing in English

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This pioneering study offers dynamic new answers to Christian Jacob's question: 'What are the links that bind the map to writing?'.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cartographies of Culture by Damian Walford Davies in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & English Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Mapping Borders: ‘Tintern Abbey’ and Literary Hydrography

SITUATING ‘TINTERN ABBEY’

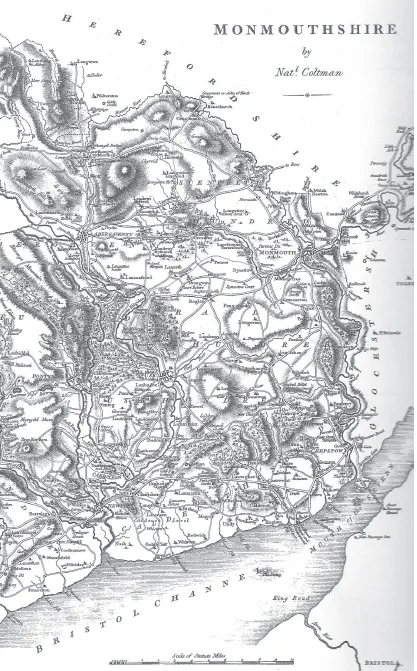

Ever since Marjorie Levinson in Wordsworth’s Great Period Poems (1986) gave us a portrait of a disingenuous poet who in ‘Lines written a few miles above Tintern Abbey’ ‘artfully assembled’ an idealized locus through strategies of displacement and sublimation, commentators have animatedly exchanged views on the poem’s geographical and psychic emplacement.1 Sensing that ‘Tintern Abbey’ ‘is an especially difficult work to situate’, Levinson audaciously sought to ‘reconstruct’ a ‘scene of composition’ and recover the components of an ‘observed’ topography in order to lay bare Wordsworth’s bad faith, his occlusion of the socio-political and his flight into the mind.2 Diagnosing the poem as a pathological ‘allegory of absence’, a transvaluation of place and its human networks, Levinson rendered the poem uncanny. The borderland landscape above, at or below Tintern Abbey (see figure 1) has been combed in the service of various arguments for and against Levinson’s brand of ‘deconstructionist historicism’3 – a methodology that has an interesting analogue, though (importantly) not a precise parallel, in the hermeneutics of suspicion governing J. Brian Harley’s seminal deconstructions of the map in the late 1980s and early 1990s as a ‘duplicitous’ social agent constituted by ‘silences’ that must be ‘teased out’ to reveal ‘how the social order creates tensions within its content’.4 Despite the clamour of voices, however, the poem’s situatedness – its localness or locatedness in the Wye Valley – has remained stubbornly intact. In part, this is no doubt due to the poem’s insistently presentist modality (its timeshifts notwithstanding), and its sense of a real landscape empirically apprehended: ‘The day is come when I again repose / Here, under this dark sycamore.’5 Indeed, the debate as to the poem’s locus has fetishized a static paradigm of the relation between poem and landscape, despite the acknowledgement that Wordsworth and Dorothy were energetically on the move from 10 to 13 July 1798. Moreover, the acts of critical emplacement referred to above have proved doubly incarcerating since they have not been sufficiently sensitive to the cultural meanings of the poem’s borderland coordinates.

Though attuned to Wordsworth’s anxious sense of ‘shifting geographical configurations and changing history’, Michael Wiley in Romantic Geography has emphasized the way in which ‘Tintern Abbey’ ‘brings narrative to a pause at a carefully situated spot and historical moment’. Wordsworth is seen to take ‘his famous meditative “stand”’, adopting a ‘stationary position’, even as he speaks of ‘both an extended region, ranging from a spot upriver of the rural Abbey ruins to urban areas, and an extended span of time’.6 Specifically concerned to ‘resolve the location’ of the poem, David Miall identifies its geographical and imaginative nodal point in the vicinity of Symonds Yat, north of the abbey – a scene whose ‘particular configuration’, Miall argues, provides an imaginative paradigm for the rest of the poem as ‘nature itself models how nature can be understood as a ground for human experience’.7 Further, James M. Garrett has recognized how Wordsworth’s ‘narrative’ depends ‘on movement through space and time’, despite the ‘stationary quality’ of the poem, which ‘gives the illusion of standing still upon a single spot of earth’.8 But while a number of critics have valuably sought to chart the poem’s various ‘movements’ – meditative, syntactical, structural – such ‘motion’ has been narrowly conceptualized as an intra-textual phenomenon. And so, despite its ‘vagrant’ currents, ‘Tintern Abbey’ has in Romantic studies been consigned to a static position in a Wye Valley rendered profoundly acultural.9 One might say that attempts to recover the originary ‘scene’ of the poem (elided or not) represent a modern critical incarnation of the obsessive picturesque debate in contemporary guides and tours regarding the most advantageous position from which to achieve a view of Tintern Abbey itself.10

Like Marjorie Levinson, I want to render ‘Tintern Abbey’ uncanny. My own strategy involves a critical ‘de-bordering’ that also serves to bring the poem into focus as a paradigmatic ‘border’ utterance – a poem of Monmouthshire and of the Welsh March that is profoundly attuned to the cultural, political and psychological impact of boundaries. Bringing ‘Tintern Abbey’ into the orbit of the discipline of Welsh writing in English while invoking other, non-literary, bodies of knowledge occasions both a necessary stranging up and a salutary naturalization of the poem as a characteristically ‘Anglo-Welsh’ inscription of shifting frontier-land identities at what Robert Stradling calls ‘an axial point of British geography’.11 In addition, I aim to replace the ‘static’ model of composition identified above with a more kinetic conception of the poem’s multiple cultural and geographical locations. I suggest that ‘Tintern Abbey’ is dynamically constituted by motion through the various frontier topographies of its composition. Thus we are able to see ‘Tintern Abbey’ not merely as a poem of the Wye (ambiguously Welsh and English) and of walking, but also as a ‘tidal’ utterance of the Severn Estuary (that other Welsh-English interspace), the Avon and the West Country, even as a ‘suburban’ utterance of Bristol. The poem’s ‘Welshness’ is hybrid – as, therefore, is its ‘Englishness’. If, as Duncan Campbell has suggested in a discussion of recent trends in Welsh writing in English, psychogeography is ‘a species of border-writing, standing uneasily between so many oppositions (mind and world, city and country, myth and history), never resolving in favour of one side or another, and above all, never forgetting’, then ‘Tintern Abbey’ is a classic text of Anglo-Welsh psychogeography whose bourdon is ‘the specific effects of the geographical environment … on the emotions and behaviours of individuals’.12 Crucially, I argue that the poem is vitally conditioned by tidal action, in both literal and figurative senses, and my ‘hydrographic’ reading seeks to reveal the poem’s response to and calibration of actual water depths and speeds of flow. Indeed, composed at the end of the very decade in which, like the ‘national work’ of the Ordnance Survey,13 hydrography was officially and professionally recognized in Britain (Alexander Dalrymple became the first hydrographer to the Admiralty in August 1795),14 the poem is itself a hydrographic map of the littoral, riverine, inter-tidal, estuarine and marine topography that conditions its utterances, and a textual inscription of the various border crossings that Wordsworth negotiated during its peripatetic composition. In that sense, ‘Tintern Abbey’ is a performance work avant la lettre – akin, in its mapping of the interdependence of body and environment, to the work of such Wales-based practitioners as the ‘movement artist’ Simon Whitehead, whose ‘experiential maps’ ‘internalise the rhythms and textures of this land’, rendering them ‘familiar, lived, part of [the] body’.15

1 Borderland – detail from Nathaniel Coltman’s county map in William Coxe’s An Historical Tour in Monmouthshire, Illustrated with Views by Sir R. C. Hoare (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1801)

The phrase Wordsworth would coin in a poem of 1813 to describe a surveyor triangulating the southern extremity of the Lake District from the summit of Black Combe – ‘geographic Labourer’ – captures the cartographic ‘work’ of ‘Tintern Abbey’ with equal force and aptness. To chart the genesis of ‘Tintern Abbey’ in such terms is to bring a poem, uncannily, into the realm of contemporary European printed ‘river maps’;16 it is also to locate the poem in the sphere of activity of Welsh poet Lewis Morris (1701–65) – self-taught pioneering hydrographer of the coast of Wales and a determining influence on British marine cartography.17 I therefore see Wordsworth’s paradigmatically ‘Romantic’ poem as at the same time paradigmatically ‘Welsh’, located in a line of descent from Morris’s maps (also considered in chapter 3). In addition, a tidal hermeneutic allows us both to confirm and to contest some of the assumptions of various historicist readings of the poem, while a cartographic rubric offers a way of revitalizing increasingly tired historicist paradigms. Over and above its supposed pantheism, its ‘pictures of the mind’, ‘Tintern Abbey’ represents a compelling psychogeographical chart. Drawing on scientific data, this chapter offers a radical geographical and disciplinary re-territorialization of ‘Tintern Abbey’. It does so by encountering a work of imaginative literature through the lens of recent theorizations located in that exciting zone between cultural geography, social theory and literary studies. Here, place becomes space – ‘dynamic, contested, and multiple in its symbolic qualities and representative identity positions’, rich in its ‘possibilities for liminal experience’.18 Himself located liminally on the cusp of the millennium, Denis Cosgrove remarked in 1999 that

In the opinion of many observers, it is the spatialities of connectivity, networked linkage, marginality and liminality, and the transgression of linear boundaries and hermetic categories – spatial ‘flow’ – which mark experience in the late twentieth-century world. Such spatialities render obsolete conventional geographic and topographic mapping practices while stimulating new forms of cartographic representation to express not only the liberating qualities of new spatial structures but also the altered divisions and hierarchies they generate. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s reference to the rhizome as a metaphor for half-submerged, non-hierarchical, open and unplanned spatial connections is a signal example.19

In this chapter I want to argue that, remarkably, Wordsworth’s hydro-graphic map of Welsh-English space anticipates these very ‘spatialities of connectivity, networked linkage, marginality and liminality’ that characterize postcolonial and postmodern experience. Further, with its commitment to ‘spatial “flow”’ and to an open, rhizomatic connection with the external environment, ‘Tintern Abbey’ offers itself as a poetic embodiment of Cosgrove’s ‘new forms of cartographic representation’. And what Cosgrove cites as a ‘third strand of the revolution in spatial representation’ from the 1970s onwards – the ‘kinetic cartography’ enabled by information technology with its ‘continuous manipulation and transformation of spatial coordinates and the data they reference’ – is likewise prefigured in the persistent adjustments, recentrings and decentrings of an Anglo-Welsh poem that theorizes itself as already post-cartographic.20

COMPOSITION GEOGRAPHY

The composition history – or, better said, composition geography – of ‘Tintern Abbey’ during the period 10–13 July 1798 is not easily recovered since Wordsworth left us with ‘alternate recollections’ of the process.21 According to the note he dictated to Isabella Fenwick, he began the poem ‘upon leaving Tintern, after crossing the Wye’ on 13 July, and ‘concluded it just as [he] was entering Bristol in the evening, after a ramble of 4 or 5 days’ with Dorothy. Wordsworth added: ‘Not a line of it was altered, and not any part of it written down till I reached Bristol.’22 However, in a letter of September 1848, the duke of Argyle informed the Revd T. S. Howson that Wordsworth had told him that ‘he had written Tintern Abbey in 1798, taking four days to compose it, the last 20 lines or so being composed as he walked down the hill from Clifton to Bristol’.23

Further contradictory evidence appears in Christopher Wordsworth’s Memoirs of William Wordsworth (1851):

We crossed the Severn Ferry, and walked ten miles further to Tintern Abbey … The next morning we walked along the river through Monmouth to Goderich [sic] Castle, there slept, and returned the next day to Tintern, thence to Chepstow, and from Chepstow back again in a boat to Tintern, where we slept, and thence back in a small vessel to Bristol.24

Crediting the evidence of the Fenwick note, John Bard McNulty in 1945 drew the logical conclusion that ‘Tintern Abbey’ was composed partly – indeed, mostly – on board the ‘small vessel’ that carried Wordsworth ‘across the Severn Estuary and up the River Avon to Bristol’.25 It is an intriguing possibility that critics have not pursued. Even the ‘orthodox’ critical position – which takes its cue from Mary Moorman’s 1957 biography and Mark L. Reed’s meticulous 1967 chronology in accepting the itinerary outlined in the Memoirs and in assuming that the poem was ‘probably’ begun on 11 July as Wordsworth walked north to Goodrich and completed on the evening of 13 July – entails the recognition that ‘Tintern Abbey’ was partly composed on river and estuary water, both eddying with tidal currents.26 This fact, I suggest, has ‘no trivial influence’ (l. 33) on our understanding of the poem. In the argument that follows, I accept the ‘received’ interpretation, sketched above, of Wordsworth’s movements and of the chronology of the poem’s composition.

THE WYE VALLEY: SHIFTING SCAPE, KINETIC SPACE

A notable feature of contemporary tours of the Wye Valley is the way in which the landscape itself is conceived as motile, and movement is established as crucial to an aesthetic appreciation of the scenery. This is observable not merely in those tours describing the fashionable boat trip from...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Crew

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgement

- Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1 Mapping Borders: ‘Tintern Abbey’ and Literary Hydrography

- 2 Mapping the Miracle: Hopkins and the Psychocartography of Welsh Space

- Plates

- 3 Mapping Islandness: Brenda Chamberlain’s CelticArchipelagos

- 4 Mapping Moatedness: Brenda Chamberlain’s European Archipelagos

- 5 Mapping Partition: Waldo Williams, ‘In Two Fields’, and the 38th Parallel

- Conclusion: The Digital Literary Atlas of Wales

- Notes

- Bibliography