![]()

1 INTRODUCTION

CONTEXT

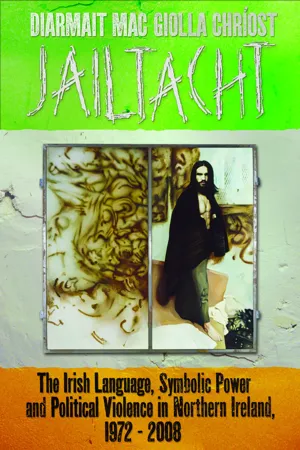

This book is set in the context of the historical ethno-political conflict that occurred in Northern Ireland during the last quarter of the twentieth century, but it is not about it. Rather, it is concerned with a very particular aspect of that conflict, namely the relationship between the Irish language and the paradigm of political violence. In short, the research object at the heart of this book is the emergence of the Irish language amongst Irish republican prisoners and ex-prisoners in Northern Ireland in the period from around 1970 up until today. It would appear that the language emerged from very unpromising conditions. Most republicans claim that they entered prison with very little or no knowledge of the language while, at the same time, the prison authorities operated a ban upon Irish language teaching materials and on the use of the language more generally. Despite this, the prisoners acquired and used the language to such an extent that it became a working language, used exclusively in parts of the prison. These developments gave rise to the popular coinage of the terms ‘Jailic’ and ‘Jailtacht’, deformations of the terms ‘Gaelic (Irish language)’ and ‘Gaeltacht (official Irish-speaking districts of the Republic of Ireland)’. The relationship between the prisoners and the Irish language has affected society outside prison. During the 1980s the language was used by Irish republicans as a tool for the ‘radicalisation’ of community groups; during the 1990s it enabled a shift in the discourse of the Irish republican movement towards political accommodation, and most recently it has been ‘commodified’ by some ex-prisoners as a product suitable for consumption by visitors keen to experience ‘struggle tourism’. Today, certain ex-prisoners serve as members of Foras na Gaeilge, a statutory body which contributes to the shaping of Irish language public policy.

Given the recent political settlement in Northern Ireland, the conflict there is often referred to as an example of the effective management and resolution of deep-rooted political violence, yet despite this the political discourse regarding the Irish language has become increasingly divisive. Recent debates on the floor of the Northern Ireland Assembly regarding the use of the language in the chamber as well as the rhetoric surrounding the campaign for an Irish Language Act in Northern Ireland illustrate this point.4 More recently again, the First Minister of the Northern Ireland Assembly and leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (Peter Robinson) had in mind the politics of the Irish language when he announced plans for a ‘Unionist Academy’ as a means of returning the fight in the increasingly intense cultural war in Northern Ireland: ‘There has been something of a cultural war in Northern Ireland. We intend to fight back’.5

Yet, as I have argued elsewhere, the Irish language has the potential to transcend traditional boundaries in Northern Ireland and be a part of the solution rather than of the problem.6 The question arises – what is the function of the Irish language as acquired, developed and used by Irish republican prisoners and former prisoners in this? This dramatic and complex linguistic phenomenon has yet to be subject to serious academic scrutiny and, as a result, is subject to widespread popular misconceptions and prejudice. Properly understanding it is a matter of some significance; it is my view that the Irish language can be looked upon as the defining symbolic element of the political violence that has shaped the history of Northern Ireland and, to a great extent, the relationship between the UK and the Republic of Ireland. In addition, the matter is of more general importance. Since 9/11 much of the research on contemporary forms of political violence in different parts of the globe is concerned with the symbolic terrain which defines the so-called new terrorism.7 This study of language and political violence delineates that viscous landscape.

METHODS

In responding to these questions I offer a text that is ambitious with regard to its philosophical and theoretical aims and which, at the same time, is thoroughly grounded in a wealth of empirical data from a variety of sociolinguistic settings. To begin with, I set out to accomplish the following basic aims:

- to describe the means of language acquisition by the prisoners, including specific teaching materials and techniques, and ascertaining the extent of the possible barriers faced by the prisoners in their acquisition of Irish, including prison policy, the attitudes of other prisoners and conflicting attitudes amongst Irish republican prisoners

- to describe the use of the Irish language by prisoners including, specifically, the reconstruction of the key phrases or language strings developed by the prisoners during the different stages of imprisonment and to identify patterns of use of this formulaic language

- to analyse the impact of the relationship between the (ex)prisoners and their form of Irish on wider society in NI, including its particular linguistic and sociological impact upon the Irish language more generally.

In order to achieve these aims, a range of data is subjected to a number of specific modes of enquiry. Amongst the most important data are the results of a series of semi-structured interviews with ex-prisoners who are, or were, important with regard to the Irish language in the Irish republican movement. Initially, contact was made with ex-prisoner organisations including Coiste na nIarchimí, Cumann na Fuiseoige and Tar Abhaile. Coiste na nIarchimí proved to be especially useful in providing a gateway to the network of former Irish republican prisoners and once this gateway had been successfully negotiated it was then possible to gain access to a wide range of former prisoners. As the fieldwork developed it was possible to use the fact of these contacts to legitimise access to other former prisoners who were not necessarily associated with organisations such as Coiste na nIarchimí. In all cases I conducted the interviews myself. This is a very distinctive feature of this research as most other investigators conduct such fieldwork (described as ‘dangerous’8 in the academic literature) by proxy, that is through using the ex-prisoners themselves as researchers. Other academic researchers have used this method because of concerns regarding personal security and also because the republican movement has chosen to make itself not easily accessible to the research community. The conduct of research by proxy reduces the integrity and objectivity of the results as there is a distance between the researcher and the object of research. The interviews were conducted in the language choice of the interviewee, allowing for code-switching between Irish and English.

As a result of contacts made during the preliminary fieldwork, I was allowed privileged access to ‘archival’ material on the Irish language held by associates of the Irish republican movement and ex-prisoners’ organisations. These include policy development documents, action research projects and covert teaching materials. In addition, I make considerable use of the autobiographical and biographical accounts of republicans, ex-prisoners and prison staff as primary and secondary sources of ethnographic material. These sources include, for example, Adams,9 Campbell et al.,10 Longwell,11 McKeown,12 Moen,13 Morrison,14 O’Rawe,15 Ryder16 and Wylie.17 The research includes the pragmatic and stylistic analysis of dramatic reconstructions and literary expressions in Jailic and of the Jailtacht. These include a screenplay for a feature film, the script for a play performed in the theatre, as well other creative writing by the (ex)prisoners. Also, relevant material from the blogs and websites of Irish republican, loyalist and other popular sources are collated and studied. In addition, a series of historical legal cases initiated by Irish republican prisoners against the authorities of HMP the Maze (aka Long Kesh) and HMP Maghaberry are examined. This includes interviews with the solicitors and barristers engaged on these cases. Amongst other interview subjects are external and invited ‘teachers’ of the Irish language of the prisoners held at HMP the Maze.

Other linguistic data is derived from the Irish language as it appeared, and indeed continues to appear, in political graffiti and murals in various parts of Northern Ireland during the period of study (much historical material has been collated and presented online via the CAIN conflict archive in the Mural Directory).18 Other extremely useful sources in this regard include the Murals of Northern Ireland Collection at Claremont Colleges Digital Library, the Ciaran MacGowan Collection at Stanford University, the published works of Rolston (various), and the Troubled Images: Posters and Images of the Northern Ireland Conflict CD-ROM collection from the Linen Hall Library, Belfast. I uncovered useful information in official archival materials held at the Public Record Office for Northern Ireland, amongst the ‘grey’ literature of the Republican movement in both English and Irish, for example in the publications An Glór Gafa, Ár nGuth Fhéin, An Phoblacht and Iris, and also in various journalistic sources in the English and the Irish language print media (both the UK and the Republic of Ireland) held in the Political and the Irish Language Collections at the Linen Hall Library. I also draw upon relevant unpublished research by other scholars based in the UK, Ireland and North America, including a number of PhD and other postgraduate dissertations in both English and Irish. Finally, all of this material is supplemented by the results of purposeful visits to the public spaces of the blogs and social network sites of Irish republicans, loyalists and ‘ordinary’ cybercitizens.

STRUCTURE

The substantive content of the book begins with a chapter on the history of the origins and evolution of the relationship between the Irish republican prisoners of the ‘long war’ in Northern Ireland and the Irish language. In this chapter I identify three different phases in this history as follows:

- 1972–1976, Internment

- 1976–1981, Protest

- 1981–1998, Strategic Engagement.

This chapter provides the reader with the detail of the historical narrative that is at the heart of this linguistic phenomenon. The relationships between the principal characters, significant events and main sites are drawn together so that the broad outlines of the story may be readily accessible, thereby enabling the reader to situate the distinctive parts of the linguistic analysis which follows in their appropriate context.

The linguistic analysis that builds upon the contextual work in chapter 2 comprises a number of distinctive modes of enquiry. These different analytical approaches are not adopted in order to be intellectually fashionable or to appeal to the widest possible audience but rather because each of them is necessary given the different types of evidence available to this particular case study. The modes I refer to are stylistics, pragmatics, semiotics, and critical discourse analysis and they each occupy a separate analytical chapter in the book. Chapter 3 is concerned with a stylistic analysis of a number of key texts which pertain to Jailic. It appears to me that the properties of the variety of language used by the Irish republicans can be said to be used distinctively and, therefore, to belong to a particular situation. In other words, they use a particular style and their language has a particular context. Using a stylistic approach, as characterised largely by Coupland,19 the particular choices made by certain individuals, and the organisations to which they belong, in their use of language are described and explained. Halliday’s theory of register, and its key concepts ‘field’, ‘tenor’ and ‘mode’, are key elements to this analysis of the relationship between semantic patterns and social context.20 To put it simply – I determine what is taking place, who is taking part and what part the language is playing.

In chapter 4 I turn to pragmatics in order to show how the subjects communicate more than that which is explicitly stated. This approach is essential to understanding the relationship between language, symbolic power and political violence for two reasons. Terrorist organisations often have severely limited access to normal means of communication due to the security policy o...