- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Williams analyses and compares the ways in which African Americans and the Welsh have defined themselves as minorities within larger nation states (the UK and US). The study is grounded in examples of actual friendships and cultural exchanges between African Americans and the Welsh, such as Paul Robeson s connections with the socialists of the Welsh mining communities, and novelist Ralph Ellison s stories about his experiences as a GI stationed in wartime Swansea. This wide ranging book draws on literary, historical, visual and musical sources to open up new avenues of research in Welsh and African American studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Black Skin, Blue Books by Daniel G. Williams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & English Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Black Skin, Blue Books: Frederick Douglass, Abolitionism and Victorian Wales

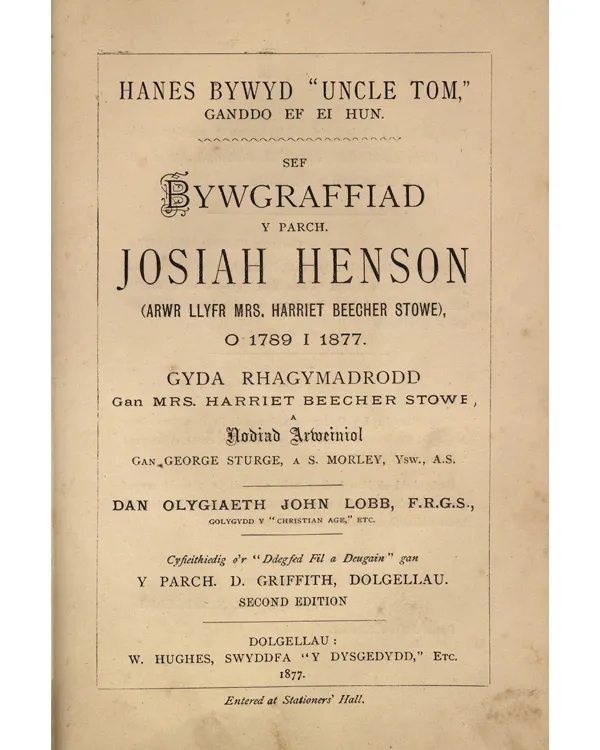

1. The Welsh translation of Uncle Tom’s Story of His Life: An Autobiography of the Rev. Josiah Henson (1876).

Having briefly visited his father’s birthplace, Hay-on-Wye, in 1883, the celebrated American novelist William Dean Howells returned to Wales in 1904 to travel widely among a people whom he described as his ‘co-racials’.1 He found some elements of Welsh culture surprising, from the ‘more than mid-Asian remoteness’ of the place names, to the popularity of the blackface minstrels that he encountered in Aberystwyth and Llandudno.

They dote upon Niggers, as they call them, with a brutality unknown among us except to the vulgarest white men and boys, and the negroes themselves in moments of exasperation. Negro minstrelsy is almost extinct in the land of its birth, but in the land of its adoption it flourishes in the vigor of undying youth; no watering-place is genuine without it . . . The decay of their gay science began among us with the fall of slavery, and the passing of the old plantation life; but as these never existed in Great Britain the English [sic] version of negro minstrelsy is not affected by their disappearance … At Llandudno the blackness of the Niggers was absolute, so that it almost darkened the day as they passed our lodging, along the crescent beach on their way to the open air theatre beyond it … There they cracked their jokes, and there they sang their songs; the songs were newer than the jokes, but they were both kinds delivered with a strong Cockney accent, and without an aspirate in its place. But it was all richly acceptable to the audience, who laughed and cheered and joined in the chorus when asked.2

While there is good reason to question the claim that the ‘gay science’ of minstrelsy had ‘decayed’ by the early twentieth century in the United States, Howells, who would participate in the founding of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) in 1909, clearly views minstrelsy in 1904 as a ‘brutal’ and ‘vulgar’ element of the British cultural landscape. The widely held view that minstrelsy was wholly based on the trivialization of black aspirations to full citizenship, and offered nothing more than white travesties and imitations of black culture, has been challenged in recent years by cultural historians.3 While fully accepting that minstrelsy reinforced a widespread belief in the hierarchy of races that justified imperial conquest and racist practices, critics such as W. T. Lhamon Jr and Eric Lott have sought to explore the ways in which particular minstrel performances interacted in complex and not always predictable ways with ethnic, gender and class identities.4 The current notion that the meaning of minstrelsy was historically contingent can be illustrated by tracing the shifting responses of Frederick Douglass, who was the pre-eminent African American abolitionist of his time and is the most widely canonized nineteenth-century African American author today. He is a figure to whom I shall return as a point of reference throughout this chapter.5

During his last visit to Europe in 1887, Douglass perceived a change in racial attitudes since his previous visits in the 1840s and 1850s. While most of the British and French remained ‘sound in their convictions and feelings concerning the colored race’, American prejudices were being adopted increasingly, reinforced by blackface minstrels ‘who disfigure and distort the features of the Negro and burlesque his language and manners in a way that make him appear to thousands more akin to apes than to men’.6 In discussing Douglass’s 1845–7 visit to the British Isles, Sarah Meer suggests that the existence of eloquent African Americans such as Douglass at antislavery meetings in Britain provided ‘a crucial counter-representation to the blackface entertainments already patronized by British audiences in the 1840s’.7 While Douglass did express concerns at the tendency of minstrel troupes to ‘exaggerate the exaggerations of our enemies’ during his first tour of Britain, he tended to view minstrelsy as a part of the abolitionist struggle at this time.8 He believed, for example, that the spectacle of an African American group, Gerritt’s Original Ethiopian Serenaders, performing to white audiences was a sign of progress, and argued that some of the songs associated with minstrelsy, such as ‘Lucy Nell’, expressed the ‘finest feelings of the human nature … [and] awaken the sympathies for the slave, in which Antislavery principles take root, grow up, and flourish’.9 Speaking to an American audience at Cincinnati in 1852 he used the popularity of ‘Nigger songs’ among whites as a basis for arguing that ‘I don’t believe you want to get rid of us after all’, and argued on another occasion that minstrel songs ‘constitute our national music, and without which we have no national music’.10 Douglass’s ambivalent feelings were expressed in his awareness that the popularity of minstrelsy was partly to account for the success of his anti-slavery speeches in Britain: ‘It is quite an advantage to be a nigger here. I find I am hardly black enough for British taste, but by keeping my hair as woolly as possible I make out to pass for at least half Negro at any rate.’11 The complex connections between minstrelsy and anti-slavery in the mid-nineteenth century is illustrated further by the fact that by 1854 Harriet Beecher Stowe’s ‘Uncle Tom’ had supplanted ‘Jim Crow’ as the leading minstrel figure. Uncle Tom was the last great role of the white performer Thomas Dartmouth Rice who had first brought the song and dance act called ‘Jim Crow’ to Britain in 1836. W. T. Lhamon argues that Rice’s Uncle Tom was ‘a revolutionary statement’ that lived up to what the New York Tribune had described as ‘the deep sentiment of human brotherhood’ that his Jim Crow performances had evoked.12

The connection between a form of entertainment that offered a grotesquely comic view of black humanity and a commitment to the struggle against slavery is embedded within the text of Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin.13 Stowe included two minstrel scenes in her novel, both associated with black children. The first occurs in the opening chapter where Harry, the son of mulatto slaves George and Eliza Harris, performs a show for his master, Shelby, who evokes minstrel conventions by referring to the boy as ‘Jim Crow’. Harry performs ‘one of those wild, grotesque songs common among the negroes, in a rich, clear voice, accompanying his singing with many comic evolutions of the hands, feet, and the whole body, all in perfect time to the music’, before being asked to ‘walk like Uncle Cudjoe, when he has rheumatism’, and to lead a psalm like ‘old Elder Robbins’.14 The way in which the scene is framed makes it clear that Stowe wishes to expose the ways in which the child’s performance is exploited in the context of a slave transaction between two masters, but the effect is to reinforce the grotesque childishness of black slaves, an impression reinforced later in the novel when Augustine St Clair buys Topsy – ‘a funny specimen in the Jim Crow line’ – for his cousin Ophelia. Topsy is told to ‘give us a song, now, and show us some of your dancing’:

The black, glassy eyes glittered with a kind of wicked drollery, and the thing struck up, in a clear shrill voice, an odd negro melody, to which she kept time with her hands and feet, spinning round, clapping her hands, knocking her knees together, in a wild, fantastic sort of time, and producing in her throat all those odd guttural sounds which distinguish the native music of her race; and finally, turning a summerset or two, and giving a prolonged closing note, as odd and unearthly as that of a steam-whistle, she came suddenly down on the carpet, and stood with her hands folded, and a most sanctimonious expression of meekness and solemnity over her face, only broken by the cunning glances which she shot askance from the corners of her eyes.

Miss Ophelia stood silent, perfectly paralyzed with amazement.15

While spoken by a third-person omniscient voice, words such as ‘unearthly’, and the reference to Topsy as ‘the thing’, suggests that we are seeing things from Miss Ophelia’s point of view. Stowe seems to be suggesting that both the grotesque performance and the way in which it is being viewed result from the inhumanity of slavery, but by the post-Civil War period this message had been lost as ‘Topsy’ came second only to ‘Uncle Tom’ as the most popular character in minstrel shows.16 Gerald Early argues that Stowe’s association of the ‘darky stage antics’ of minstrelsy with the black child was damaging in two ways:

It strongly reinforced in the minds of whites, who already in the 1850s were waxing sentimental about ‘the old plantation’, sentimentality and nostalgia for ‘darky’ antics, by connecting them with children and childhood. It also, contrarily, distinguished black children as being apart from white children, and thus separated the idea of black childhood from white childhood, linking black children to deviltry, mischief, silliness, and an intensely exhibitionist nature.17

Early concludes his analysis by noting that it is ‘one of the curious paradoxes of American culture’ that Uncle Tom’s Cabin, ‘so sincerely and powerfully antislavery, should have so successfully trapped blacks in a series of images that so thoroughly discounted their humanity while so fervently pleading for their character’.18

Early offers a convincing account of a widely held view of Stowe’s novel. This was not the view at the time of its publication, however, for it was welcomed by abolitionists as ‘a godsend destined to mobilize white sentiment against slavery just when resistance to the southern forces was urgently needed’.19 If William Dean Howells was perturbed by the presence of minstrels in Llandudno, he believed that Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin was ‘one of the great novels of the world, and of all time’. Writing in 1897 he argued that America had no real novels until after the Civil War, ‘except Uncle Tom’s Cabin’, a book that transcended its time and place: ‘The fact that slavery was done away with does not matter; the interest in Uncle Tom’s Cabin will never pass, because the book is really … true to human nature.’20 In his third and final autobiography of 1893, Frederick Douglass described Stowe’s novel as ‘a work of marvellous depth and power’, noting that ‘nothing could have better suited the moral and humane requirements of the hour’.21 This view was consistent with the laudatory reviews and references to the novel that appeared in Douglass’s abolitionist journal The Frederick Douglass Paper when Uncle Tom’s Cabin first appeared in 1852. Robert Levine notes that Douglass consistently championed the unprecedented impact that the novel was having on readers not only in the Northern states, but in the South and across the Atlantic as well.22 In drawing attention to its success in places such as Paris and Moscow, Douglass was reinforcing his argument that ‘Uncle Tom has his mission in Europe, and most conscientiously is he fulfilling it’.23 Further evidence for the novel’s transatlantic impact was offered in the ‘Literary Notices’ section of the Frederick Douglass Paper of 31 December 1852, where readers were told that ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin has been translated into Welsh, and bears the title of “Caban F’Ewythr Tum”’ (sic).24

The first full-length Welsh version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published by John Cassell in London in 1853, in a translation by Hugh Williams with illustrations by George Cruikshank. Chapters had already appeared in the Liverpool based Welsh newspaper Yr Amserau (The Times) in 1852, and in March 1853 the journal Y Cyfaill o’r Hen Wlad (The Friend from the Old Country) could report that there were three different Welsh versions of Stowe’s novel in circulation, translated respectively by Hugh Williams, Williams Rees (‘Gwilym Hiraethog’) and Thomas Lefi (‘Y Lefiad’).25 In addition to Y Cyfaill o’r Hen Wlad, the Welsh-American journal Y Cenhadwr Americanaidd (The American Missionary) also serialized the novel, and its editor Robert Everett produced an amended version of Hugh Williams’s translation for an American audience in 1854.26 Welsh-language translations of English and European texts were widespread in nineteenth-century Wales, but even in the context of a thriving translation industry the sheer number of versions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin produced within a two-year period is remarkable.27 It is clear that Stowe’s novel resonated with Welsh audiences. While many no doubt read the story as a tale of exotic ‘others’, William Rees’s transposition of the story into a Welsh context in his Aelwyd F’Ewythr Robert (‘Uncle Robert’s Hearth’, to which I shall return) suggests that some sought to make connections and correspondences between New England anti-slavery, the African American experience and nineteenth-century Wales.28 If, as Gerald Early suggests, the success of Stowe’s novel derived partly from the fact that it ‘came along at a time when American popular culture was developing a consensus view about a number of American types’, then, in translating ‘old Elder Robbins’ in the passage from chapter 1 quoted above as ‘hen Robin y blaenor’ (‘old Robin the [chapel] deacon’), African American types became familiar Welsh types, a process perhaps reinforced by the fact that the story’s central African American family have a familiar Welsh surname – Harris....

Table of contents

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- General Editor’s Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1: Black Skin, Blue Books: Frederick Douglass, Abolitionism and Victorian Wales

- 2: ‘In the Wide Margin’: Modernism and Ethnic Renaissance in Harlem and Wales

- 3: ‘They feel me a part of that land’: Paul Robeson, Race and the Making of Modern Wales

- 4: The Invisible Man’s Welsh Routes: Ralph Ellison in Wartime Wales

- Conclusion: 1945

- Notes

- Bibliography