- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In July 1789 George Cadogan Morgan, born in Bridgend, Wales, and the nephew of the celebrated radical dissenter Richard Price (1723-91), found himself caught up in the opening events of the French Revolution and its consequences. In 1808, his family left Britain for America where his son, Richard Price Morgan, travelled extensively, made a descent of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers by raft and helped build some of the early American railroads. The adventures of both men are related here via letters George sent home to his family from France and through the autobiography written by his son in America.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Travels in Revolutionary France and a Journey Across America by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Richard Price Morgan

A Journey Across America

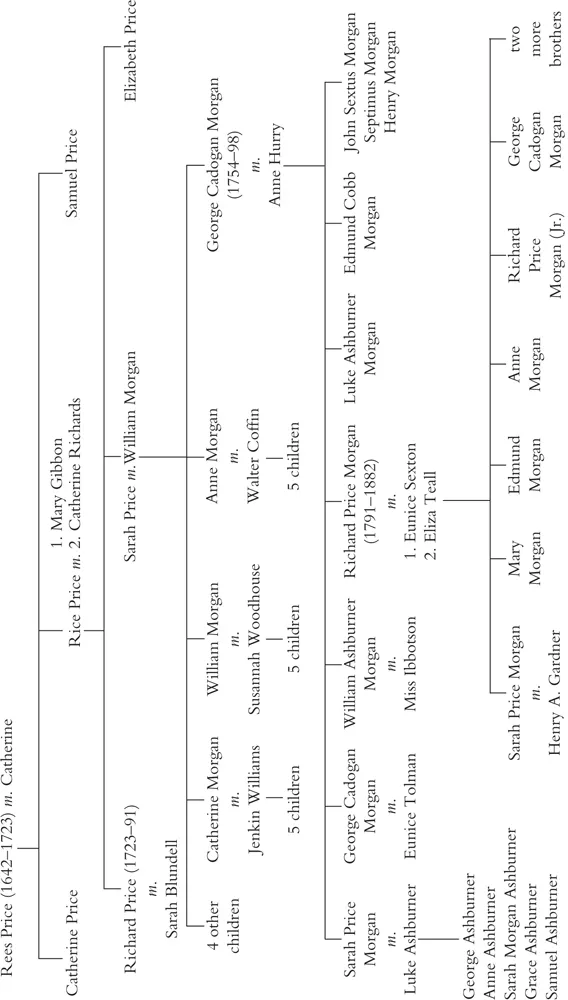

Figure 3. Price/Morgan family tree – abridged

Introduction

During the nine years that separate the 1789 Paris adventure of George Cadogan Morgan from his death in 1798, events occurred in France and Britain that we might expect to have undermined, as they did for many others, his radicalism, his republicanism and his support for the revolutionary route to change. Not only had his acquaintance Tom Paine been outlawed from Britain for writing the seditious tract Rights of Man (1791–2), he had also been imprisoned in Paris, under sentence of death, for advocating the banishment rather than the execution of Louis XVI (a policy advocated also by George Cadogan Morgan). The same period saw the execution of the king, the rise and fall of Robespierre, the Terror, and the start of a war between France and Britain. In Britain itself, Pitt the Younger began curbing homegrown radicalism by suspending Habeas Corpus in 1794 and passing the Treasonable Practices and Seditious Meetings Acts in 1795. A French invasion of Ireland was attempted in 1796 and another into west Wales in February 1797. There followed fleet mutinies at the Nore and Spithead, and in the spring of 1798 a major rebellion erupted in Ireland. Yet, despite all this, George Cadogan Morgan remained committed to his radical opinions. That we know this is due, in part, to the ‘Autobiography’ of his son Richard Price Morgan (1791–1882), which constitutes the final text in this volume. Part memoir, part travelogue, it encompasses the history of the Morgan family up to George Cadogan Morgan’s death in 1798, the family’s subsequent life in Britain, their emigration to the United States in 1808 and Richard Price Morgan’s own travels in the American west and his later life as a farmer and canal and railroad engineer.

Another recently discovered voice from the Morgan family is that of Sarah Morgan Ashburner, the daughter of George Cadogan’s eldest child, Sarah Price Morgan. Her unpublished memoir gives much additional information on the Morgans’ life in Britain, their decision to emigrate to America and their early life at Stockbridge, Massachusetts.1 There are, however, significant differences of tone and content between the two texts. As Sarah indicates, her memoir relies on ‘the conversation of a Miss Sharpe’ and her ‘details are few and not sufficient’.2 Generally, therefore, priority has been given here to factual details in Richard’s ‘Autobiography’, which were after all written by someone who was present at the events described. The difference in the two writers’ evaluations of the emigration itself is very striking, however, suggesting considerable conflict within the family at the time.

The last years of George Cadogan Morgan 1791–8

Evidence for George Cadogan Morgan’s continuing radicalism in his last years comes from three sources. The first is the praise given to republican government in his publication, An Address to the Jacobine and other Patriotic Societies of the French (1792), reprinted above. The second is another of his published works, the two-volume Lectures on Electricity published in Norwich in 1794, the year Pitt began his repression of British radicalism. The ‘Introductory Lecture’ in volume one of this work contains an enthusiastic and, at a time of revolution in nearby France, potentially dangerous endorsement of the rebel and founding father of that more distant American republic, Benjamin Franklin. ‘No tyrannicidal hero,’ wrote Morgan, ‘had ever proved more beneficial to his species, than the republican, who, when he had disarmed the clouds of their fury, armed his countrymen on the very same spot in the cause of freedom and humanity.’ That ‘very same spot’ was Philadelphia, on the Delaware River, where America’s Independence had been declared in 1776. He continues:

will not eminence belong to the example and intellectual greatness of Benjamin Franklin, who, when he had wrenched the thunder bolt from the grasp of tyranny and fraud, enrolled himself amongst the heroes of his country, chased away the minions and mercenaries of oppression, and amongst the ruins accumulated by despotism in the fury of its dying hour, established the first free community that ever blest the eyes of men?3

Morgan got to know Franklin in London through his uncle Richard Price (1723–91). Originally from Llangeinor in south Wales, Price was a Londonbased Dissenting minister who spoke and wrote on many issues, including moral philosophy, mathematics, demography, political and electoral reform, religious toleration, civil liberties, old age pensions, annuities, life assurance and the dangers of a national debt (on the subject of which he was consulted by Pitt).4 Price supported the Americans in their revolution and, in his last public sermon A Discourse On The Love of our Country, given in November 1789, he also supported the opening events of the French Revolution, igniting what is now known as the ‘Revolution Controversy’ and spurring Edmund Burke to publish his Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) in answer to Price’s ‘wicked principles’. Richard Price died on 19 April 1791 and his funeral cortège included more than fifty coaches, the pall being carried by, among others, Joseph Priestley. Many Jacobin Societies in France expressed their sorrow at the demise of a man they called the Apostle of Liberty; Horace Walpole, though, viewed Price’s death as fortunate for all those who hoped to die peacefully in their beds.5 It was after this radical uncle that George Cadogan Morgan named his son – Richard Price Morgan – who was born in 1791, the year Richard Price died. And it is in the son’s autobiography that we find the third line of evidence confirming Morgan’s continuing radicalism.

One of the earliest memories recollected by Richard is of sitting on his father’s knee as a five-year-old in 1796 and hearing him sing the Revolutionary song ‘Ça Ira’, which had first appeared in 1790, quickly accruing new lines, including those advocating the hanging of aristocrats from lamp-posts. We do not know which version the boy heard, but the fact that it was sung to him circa 1796, after the execution of Louis XVI, certainly suggests that his father had not lost his republican spirit. Richard also recalls the political meetings held at his family’s house in Southgate, near London, and his father’s involvement with radicals such as Thomas Hardy, whom he describes as a ‘particular friend’.6 Though deeply unsettled by the Treason Trials of 1794 and Pitt’s regime, Morgan did not change his opinions; even a few months before his death in October 1798 he was writing to his mother telling her of the horrific consequences of the Irish Rebellion in May that year and of what he called ‘aristocratic opinions’ of such events. Yet, while evidence of Morgan’s post-1789 radicalism constitutes a major part of the importance and interest of his son’s work, the account also provides us with an insight into the aftermath of the French Revolution and its continued influence on the lives of this family of Anglo-Welsh descent.

Morgan family life in Britain after 1798

Following George Cadogan Morgan’s death in November 1798 his family entered on a life of peripatetic though always genteel poverty. As they moved from one set of relatives to another, including George Cadogan’s brother, the actuary William Morgan, at Stamford Hill,7 the family began gradually to break up. Richard’s sister, Sarah Price Morgan, married and left for India with her husband Luke Ashburner, while one of his brothers, George Morgan, set off to scout out prospects in America – a ‘first foolish step’, according to Sarah Morgan Ashburner, for George ‘knew no business . . . was kindly . . . and about as fit as Moses Primrose8 to go forth among men and into the great greedy world’.9 Though we might also expect that with the death of their father and the gradual break-up of the family the Morgans would now lose touch with their roots in south Wales, this was not the case and Richard’s account describes in some detail a visit to south Wales and the birthplace of his father, grandfather and namesake Richard Price. While there he visited numerous cousins, aunts and uncles, some of whom were destined to become prominent figures in the early nineteenth-century industrial development of south Wales. It would also be to Llandaff in Cardiff that his mother, Mrs Anne Morgan, would return to tend her dying daughter, Sarah Price Morgan, on her return from India.10

As the family moved around the country the French situation continued to impact on their lives in various ways. Exiles from France came to live with and teach the Morgan children, among them a French governess and a French Catholic priest: the presence of the latter suggests a continuation in this Dissenting family of the religious tolerance exhibited by their father and his uncle Richard Price, despite both men’s Protestant dislike of Catholicism. In 1802 Anne Morgan’s youngest brother, the shipping merchant Ives Hurry, was taken prisoner in the English Channel: he would spend the next few years ‘under circumstances of peculiar severity and injustice’ at Verdun in France.11 Remarkably, ‘he escaped in disguise, made his way through France to the shores of the Mediterranean, and got safely home’; an adventure which was, according to the family memoir, ‘the more wonderful because Mr Ives Hurry was a man upwards of six feet in height and large in proportion’. 12 Prisoners of war must have been much in mind, therefore, especially when the family moved to live in a house near Gosport which backed onto Forton military prison, a place housing many French prisoners, as it had Americans during an earlier revolutionary war. From Gosport the family’s last journey in Britain would be to the docks at Clifton in Bristol, there to await a ship to take them to a new life in the United States.

In 1773, prior to the American War of Independence, Richard Price had written: ‘America is the country to which most of the friends of liberty in this nation are now looking; and it may be in some future period the country to which they will be all flying’.13 He could hardly have expected that this would be the fate of his own descendants. As we have seen, there is evidence that the family considered emigration to the United States as early as 1794,14 at the time when George Cadogan Morgan was expressing his enthusiasm for Benjamin Franklin, and the British government was clamping down on radicalism. ‘In the days of Pitt,’ noted Sarah Ashburner Morgan, when ‘the Priestley riots were still fresh in people’s minds . . . many independent liberal people were greatly alarmed at the progress of arbitrary government, and talked much of migration.’15 One member of the Morgan family deeply impressed by this ‘prevailing talk’ of emigration was Sarah Price Morgan’s new husband Luke Ashburner and it was he who advised Anne Morgan, in the wake of her husband’s death, ‘to emigrate, to remove her eight fine boys to a land where the world was all before them – an open field for talent and industry – noble institutions – no blight of aristocracy – nothing to check the ardour of enterprise – the advantages of education and knowledge.’ Luke, indeed, apparently considered Europe ‘a barrel of gunpowder’ waiting to explode.16 By the time the Morgan family came to leave Britain in 1808 Europe had witnessed the extraordinary rise of Napoleon who, in Richard’s words, went from being the ‘champion of freedom and progress’ hailed by ‘true republicans’ to a ‘recreant to the cause, by making himself Emperor of France’ in 1804.

In such circumstances, emigration to America in the hope of a new and improved life clearly seemed the best option; but from within the family there was considerable opposition. According to Sarah Ashburner, not only were her grandmother’s sisters, her relations and her friends all against it, but so was her late husband’s brother, William Morgan of Stamford Hill, who ‘was indignant and so angry at the suggestion that his opposition did no good’.17 Selling a valuable house in London left to them by Richard Price the Morgans realized ‘all the money they could command preparatory to investments in the New World’ and began their journey.

Departure for the New World 1808

In 1808 Richard Price Morgan and his family embarked at Bristol on the American ship Anne Elizabeth and set sail for a new life in the United States. But even as their ship began its journey the French situation intruded itself once again, this time in the shape of a flotilla of British ships assembling in a convoy for mutual protection. The ‘Yankee captain’ of their own vessel was also worried at the prospect of being boarded by French privateers, despite America’s neutrality in the war between Britain and France. With their transatlantic connections, the Morgans would certainly have been aware of the dangers of an Atlantic crossing at a time of war, or indeed any other time. During the years leading up to the American War of Independence Richard Price had entertained a number of eminent American visitors to London, among them Henry Marchant, the attorney general of Rhode Island. Following his return to America in 1772 Marchant wrote to Price vividly describing the onboard dangers of an Atlantic crossing and what might await even those travellers who reached their final destination:

I arrived at Boston after Eight Weeks Passage. The latter part of it we had very disagreeable Weather, and once were in Great Danger of being consumed by Fire, thro’ the Carelessness of the Carpenter who had left a Pot of Pitch on the Fire, which boiled Over, catched into a Flame and set on Fire the Caboose [ship’s galley], but we were so happy as in a few Minutes to extinguish i...

Table of contents

- Travels in Revolutionary France & A Journey Across America by George Cadogan Morgan & Richard Price Morgan

- Contents

- Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- George Cadogan Morgan Travels in Revolutionary France

- George Cadogan Morgan Address to the Jacobine Societies (1792)

- Richard Price Morgan A Journey Across America

- Select Bibliography