- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

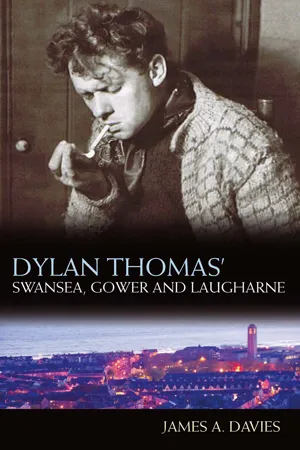

Dylan Thomas's Swansea, Gower and Laugharne

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dylan Thomas's Swansea, Gower and Laugharne by James A Davies in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Swansea – ‘the best place’

Background – from Jack to ‘D.J.’

IN 1899 A YOUNG man in his early twenties, from a Welsh-speaking, chapel-going, working-class family in Johnstown, then a village near Carmarthen, came to work in Swansea. That summer he had been awarded first-class honours in English by the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth, the only student of English in all three colleges to take a ‘first’ that year. He came to Swansea to take up a temporary post as an English teacher at Swansea Grammar School. His academic brilliance would have encouraged him to regard this appointment as a stepping-stone to better things, possibly to an academic post or, perhaps, to a position as an inspector of schools or director of education. He also had literary ambitions and was trying to publish poetry. But all his dreams faded. He got nowhere as a poet and, apart from a brief period at Pontypridd Grammar School during 1900 and 1901, he spent his whole career, until retirement in 1936, in the school to which he came in 1899.

This young man was David John Thomas, ‘Jack’ to his family, who became ‘D.J.’ the schoolmaster and Dylan Thomas’s father. Coming to Swansea must have filled him with nervous excitement. Founded, so it was said, by a Viking named Sweyn, Swansea (‘Sweynsei’) was essentially a twelfth-century Norman creation, part of the Marcher Lordship of Gower. It became a place of strategic importance: the castle commanded the mouth of the River Tawe. Later it developed as a port and a market town that by the eighteenth century was mainly English speaking. In 1786 it was advertising itself as ‘the Brighton of Wales’, seeking to exploit the rising popularity of sea-bathing in order to reinvent itself as a fashionable resort. Assembly rooms, a reading society, circulating libraries and a theatre duly appeared. But genteel ambitions literally went up in smoke with the rise of metallurgical industries – copper smelting, particularly, plus zinc smelting and tinplate manufacture – fuelled by rich and easily accessible coal seams. Victorian Swansea became ‘Copperopolis’, ‘Tinopolis’ and the ‘metallurgical capital of the world’.

By 1899 the town’s industrial heyday had probably passed, but it was still a smoky, prosperous, sprawling place of works, factories and railways, a place ‘rooted in heat and flames’. The town centre had narrow, bustling, cluttered streets, with chapels, churches, schools, theatres, cafes, restaurants and pubs, as well as fetid slums and alleys. When the wind blew from the east it brought factory smoke and smells. In the docks, which, in the years up to the Great War, continued to thrive and expand as the west Wales coalfield developed, ships disgorged hundreds of seamen into sleazy, sometimes violent pubs, brothels and cheap lodging houses. In the manner of all boom towns it continued to build monuments to its own magnificence. In 1899 Ben Evans, the huge department store, was barely five years old. It was followed by the head post office in Wind Street (1901), then the Harbour Trust Building (1903), the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery (1910), the Central Police Station (1913), and the Coal Exchange Building (also 1913). Swansea was not at all like Aberystwyth, let alone Johnstown. To David John Thomas, the young product of smaller and quieter places, it must have offered a cultural and environmental shock of seismic proportions.

The poet Edward Thomas, who had relations in the area and knew it well, wrote of being taken up ‘to Town Hill … to see the furnaces in the pit of the town blazing scarlet, and the parallel and crossing lines of lamps, which seem, like the stars, to be decoration. If it is always a city of dreadful day, it is for the moment and at that distance a city of wondrous night.’ The contrasts intrigued him: glimpses of the sea from ‘sunless courts’, the sooty town on the superb bay. He was fascinated by industrial Swansea. But he also noticed villas built around the bay and, to the west of the town centre where the prevailing westerlies kept smoke and grime away, the beginnings of middle-class suburbia.

By 1914, the year in which Edward Thomas’s essay on Swansea appeared in the English Review, David John Thomas, now always ‘D.J.’ to his colleagues, despite increasing bitterness at what had become his professional lot, had established himself as a teacher of English. In 1903 he had married a local girl, Florence Williams, from the St Thomas area of Swansea’s east side, on the edge of dockland. Her father, like D.J.’s, was a railwayman and, like D.J. himself, George Williams was from Carmarthenshire, in his case from the rural peninsula between Carmarthen and Llansteffan. His daughter Florence was a seamstress in a local draper’s. On the face of it, this was a strange marriage for an ambitious, highly intelligent, professional man who was also something of a dandy and very conscious of his own dignity. Almost certainly, as used to be said, he ‘had to marry her’; in 1904, their first child, which did not survive, was born in the small terraced house which the couple rented at the top of Sketty Avenue, then on the edge of farmland. Little more is known of their early married life; all else has vanished into the murk of Edwardian Swansea that, in its turn, has disappeared almost completely. But we know the marriage survived. A daughter, Nancy, was born in 1906, by which time they had left Sketty for more rented accommodation at 31 Montpellier Terrace and 51 Cromwell Street in central Swansea.

In 1914 Nancy was eight, and Florence pregnant. During the summer in which Britain declared war on Germany, D.J. moved his family from Cromwell Street to become the owner of newly built 5 Cwmdonkin Drive in the expanding Uplands area of west Swansea. In doing so he became part not only of the expansion glimpsed by Edward Thomas but also of the fundamental change in Welsh society during the early years of the twentieth century: the appearance of a substantial middle class and of middle-class suburbia. Only in the larger places – the Radyr, Rhiwbeina and Roath Park areas of Cardiff, the Mumbles, Sketty and Uplands parts of Swansea, possibly in Newport – was it possible for that suburbia to emerge. In Wales, where quite often the professional man lived close to the manual worker – as, for instance, in the valleys of south Wales even into the 1950s – this was a wholly new social phenomenon.

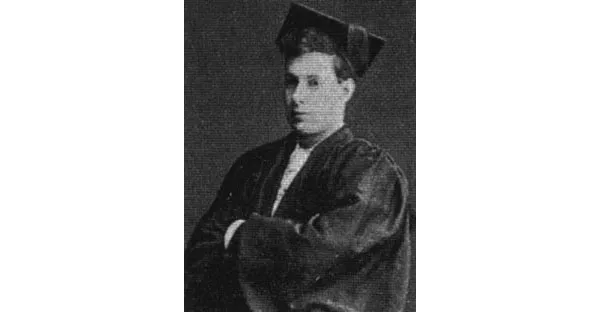

David John Thomas. Dylan’s father. His graduation photograph (c.1899– 1900), academic cap worn jauntily, reveals a handsome young man confidently awaiting the success that never came.

Dylan Thomas’s Swansea

Dylan Marlais Thomas was born on 27 October 1914 during, as he once said, the first battle of Ypres. His middle name came from his father’s uncle, William Thomas, who wrote poetry and prose in Welsh under the bardic name of Gwilym Marles, taking the latter name, pronounced ‘Marrless’, from the Marlais stream near his birthplace close to Brechfa. William Thomas had been educated at the University of Glasgow, before becoming a Unitarian minister and schoolmaster in Cardiganshire whose turbulent inclinations led to eviction from his chapel for supporting tenants against landowners. He died in 1879, aged only forty-five. Socially and intellectually, Gwilym Marles was the family’s high-flyer and D. J. Thomas was obviously proud of the connection. Daughter Nancy’s full name was ‘Nancy Marles Thomas’; it was said that her brother was named ‘Marlais’ because no one ever pronounced ‘Marles’ correctly.

In 1914 Swansea was a town (it became a city in 1969) with a population of about 100,000 divided fairly sharply between two areas. To the east around and beyond the river was industrial and working-class Swansea. To the west, where Dylan Thomas was born and grew up, was the generally prosperous, anglicized, mainly pious and comfortable, middle-class world. Indeed, the Uplands of his day has been described by the social historian Peter Stead as a ‘sophisticated middle-class suburb, in which bards, ministers and academics were thick on the ground’. It was – and to some extent remains – self-contained, with a shopping centre, private schools, churches and chapels, parks, a cinema and respectable pubs and clubs. The town centre, Swansea Grammar School, the new University College, the county cricket and rugby ground at St Helen’s, were all within walking distance or a short tram-ride away. As has been noted, like most of central Swansea it was predominantly English-speaking, particularly in Dylan Thomas’s own generation. For D.J. and many like him Welsh belonged to the old, poor, rural world from which they had escaped, one that they certainly did not intend their children to inherit. The Uplands middle class, though, was essentially Welsh in that its occupational range was wider and its gradations diff erent from, say, parts of Surrey – a schoolteacher, for example, probably had more social status in Swansea. And, like all such areas, it had its share of snobbishness and affectation: Paul Ferris, himself a Swansea boy, in his biography of Dylan Thomas, recalls the barbed joke that, in middle-class Uplands, sex was what coal came in.

As a grammar-school master teaching boys who, certainly in the early part of his career, were sifted socially through entrance examinations and fee-paying, with almost absolute power in the classroom and short working hours, D. J. Thomas enjoyed something of a gentlemanly existence. This was not, however, a source of contentment. He had few friends and was open in his disdain of both his work, which he thought beneath his intellectual abilities, and his less well-qualified colleagues. He was sharp-tongued, could be foul-mouthed and – perhaps significantly, given his son’s fatal addiction – was a regular and sometimes heavy drinker. These were persistent working-class attitudes in a bourgeois world. He was also agnostic at a time of buoyant church and chapel attendance and, in a sober-suited world, he was something of a dandy. All such characteristics we might now understand as the consequences of being trapped in an unsatisfactory marriage and of the tensions of social mobility. Certainly he was never at ease, let alone content, in a world dominated by mortgagees with pretensions to gentility.

D.J. was not required to fight in the Great War and so carried on teaching. Meanwhile, Swansea’s docks, railways and works boomed with the war effort, as did agriculture in west Wales. This was, though, the last flourish of the old world; the war was ‘a massive watershed’. In 1918 and through the 1920s the town mourned and came to terms with the carnage of the Western Front. The Great War fascinated the young Dylan Thomas: one of his early memories was hearing of ‘a country called “The Front” from which many of our neighbours never came back’. He wrote a number of school-magazine poems on the subject; one, ‘Missing’, about a soldier lying dead on a battlefield, was for the war’s tenth anniversary in 1928, when the poet was fourteen. The war remained an important and, at times, explicit presence in his first two volumes of poetry, as, for example, in ‘I dreamed my genesis’, where he wrote of

shrapnel

Rammed in the marching heart, hole

In the stitched wound and clotted wind, muzzled

Death on the mouth that ate the gas.

In the stitched wound and clotted wind, muzzled

Death on the mouth that ate the gas.

Swansea was not immune to the effects of the slump that devastated much of Wales in the 1920s and 1930s. At its worst 10,000 of the town’s workforce were unemployed and, in east Swansea, there were pockets of dreadful poverty. We catch glimpses of this in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog, the fictional recreation of 1930s Swansea, when Thomas describes the unemployed as ‘silent, shabby men at the corners of the packed streets, standing in isolation in the rain’, the scavengers along the railway lines, and the homeless ‘tucked up in sacks, asleep in a siding, their heads in bins’. The then vicar of Swansea, Canon W. T. Harvard, all too aware of the town’s abrupt social divisions, deplored the fact that ‘one half of the world did not know how the other half lived’. This was a comment that could also have been directed at Dylan Thomas and his friends: they knew comparatively little of the east side.

Yet Swansea survived the Depression better than most Welsh places. Demand for anthracite coal and tinplate continued, which helped to keep the docks buoyant and service industries to survive. In Swansea’s western suburbs it was domestic employment that helped to keep the wolves from many working-class doors. The Thomas family in its new semi-detached house was typical in employing a maid who lived in, as well as a regular washerwoman; Patricia, in Dylan Thomas’s short story, ‘Patricia, Edith, and Arnold’, is based on one of the former.

Swansea between the two world wars was a lively place with its fine buildings, churches and chapels, theatres, cinemas, clubs, pubs, cafes, sports teams and newspapers. It was a powerful focal point not only for its own suburbs but for west Wales as a whole. This was Thomas’s ‘ugly-lovely’ atmospheric town, crammed, for the most part, between hills and the magnificent sweep of the bay. It was, as perhaps it had always been, a frontier town where urban, English-speaking Swansea met the rural Welsh-language heartlands of west Wales and the Swansea Valley, and tried to keep its distance from urbanized but Welsh-speaking Llanelli. Within the town itself, the East Side and West Swansea created their own edgy lines of demarcation.

Swansea had two mainline railway stations, High Street and Victoria, the latter near where the present-day leisure centre stands, and other smaller ones. Until 1936 the town was also criss-crossed by tram routes. Tram-like carriages (the Mumbles train) still ran round the bay to Oystermouth, a small fishing village that had developed into a residential suburb that was also a centre for boating, sailing and holidays, and to Mumbles with its pier. The schizophrenic nature of the town persisted, not only between east and west but also, even more abruptly, between the solidly bourgeois commercial and shopping centre of High Street and Wind Street (always pronounced ‘Wine Street’) and the sleazy, sometimes violent, port district that included the Strand, in places less than twenty yards away from respectable streets. This juxtaposing of order and seeming chaos, of the familiar and the disorientating, this sense of being able to slip so easily from one to the other, all so vividly illustrated by the town’s topography, often finds its way into Thomas’s work and, strangely but tragically, into his personal life.

Even through the economically depressed 1920s and 1930s the town continued to expand. When Thomas was very young he had played in the fields above Cwmdonkin Drive, but in the late 1920s most of these disappeared under the Townhill Council Estate. Uplands and Sketty themselves continued to develop as transport improved and the inevitable westward drift away from polluted industrial areas took place. Such expansion, however, masked fundamental industrial decline. Copper smelting, and the many other associated metallurgical activities that had once been the vibrant basis of the town’s prosperity, ended in 1921; by 1939 almost every local colliery had closed. Swansea was sustained by being a commercial and shopping centre, by a continuing iron and steel industry, the beginnings of the oil industry and through a still flourishing port. But it had long ceased to be a boom town.

By mid 1937 both children were married – Dylan to Caitlin Macnamara, despite parental opposition – D.J. retired and he and Florence had let 5 Cwmdonkin Drive (it was not sold until 1943). They moved to another semi-detached house in Bishopston, on the Gower peninsula. They stayed there until spring 1941 when German bombing of nearby Swansea forced them to Blaen-cwm in rural Carmarthenshire, where D.J. had inherited a small cottage. During the short period spent in Bishopston, Swansea had changed almost beyond recognition.

Industrial Swansea had a good war. Works and factories poured out munitions, and the docks were of great strategic importance. But for the town itself the war was a disaster. Because of the port’s importance it was targeted by the Luftwaffe, which began attacking Swansea in 1940. The ‘Three Nights’ Blitz’ of 19, 20 and 21 February 1941, seemingly intended for the docks, instead devastated forty-one acres of the town centre, killing 230, injuring 409, and making over 7,000 people homeless. Some 857 premises were destroyed or irreparably damaged. Dylan and Caitlin Thomas, visiting D.J. and Florence at Bishopston, saw it all for themselves on 22 February. Bert Trick, an old friend of Thomas’s, met the couple in the ruined streets. ‘Our Swansea is dead’, Thomas said to Trick, and was close to tears.

In February 1947, during a bitter winter, Dylan returned to Swansea to research ‘Return Journey’. He walked around the town making notes, and later he wrote to the Borough Estate Agent for the names of shops in vanished streets. The debris had been cleared and the roads...

Table of contents

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Chronological Summary

- 1 Swansea – ‘the best place’

- 2 Gower – ‘the loveliest sea-coast’

- 3 Laugharne – ‘this timeless, mild, beguiling island’

- Further Reading