- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

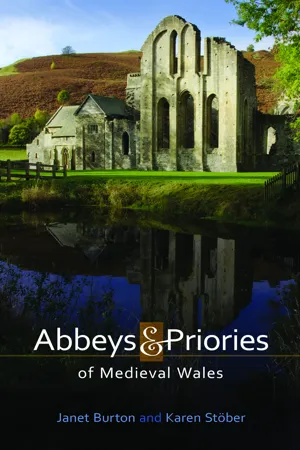

Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales

About this book

Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales is the first comprehensive, illustrated guide to the religious houses of Wales from the twelfth to sixteenth centuries. It offers a thorough introduction to the history of the monastic orders in Wales (the Benedictines, Cluniacs, Augustinians, Premonstratensians, Cistercians, the military orders and the friars), and to life inside medieval Welsh monasteries and nunneries, in addition to providing the histories of almost sixty communities of religious men and women, with descriptions of the standing remains of their buildings. As well as a being a scholarly book, a number of maps, ground plans and practical information make this an indispensable guide for visitors to Wales's monastic heritage.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales by Janet Burton,Karen Stöber in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Religious Architecture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Wales PressYear

2015Print ISBN

9781783161805, 9781783161799eBook ISBN

9781783161829ABERCONWY

(LATER MAE NAN) CISTERCIAN ABBEY

Dedication: St Mary

Diocese: Bangor (Maenan: St Asaph)

Grid reference: SH7816377526 (Maenan: SH7897365683)

Old county: Caernarfonshire

Local authority: Conwy

Ownership and access: public access to the church, which is in the ownership of the Representative Body of the Church in Wales (Maenan: no remains; site now occupied by a hotel)

HISTORY

THE BRUT Y TYWYSOGION notes that in 1186 a colony of monks was sent from Strata Florida to found a monastery at Rhedynog Felen near Caernarfon, in the lordship of Arfon. The founder may well have been Rhodri ab Owain Gwynedd (d. 1195), who was lord of Arfon at the time of the foundation and who was married to a daughter of the Lord Rhys, patron of Strata Florida. Such a connection could well explain the choice of Strata Florida as mother house of the new colony. Rhodri’s nephew, Gruffudd ap Cynan, was also a benefactor of Aberconwy; he was buried at the abbey, having taken the habit there before his death in 1200. His son, Hywel, was similarly afforded the privilege of interment (1216). The site was not occupied for long before (by 1192) the community moved to Aberconwy, at the mouth of the River Conwy. Rhedynog Felen was retained as a grange of the abbey. The most significant benefactor was Llywelyn ab Iorwerth, Llywelyn Fawr (d. 1240), who took the habit at the abbey and was buried there. His stone coffin may now be seen in Llanrwst church. Llywelyn’s second son and successor, Dafydd, was also buried at the abbey (1246) and two years later the abbots of Aberconwy and the mother house of Strata Florida journeyed to London to ask King Henry III for the body of Llywelyn’s elder son, Gruffudd, who had been killed while trying to escape from the Tower of London. He too was interred at Aberconwy. It may have been the close connection between the abbey and the house of Gwynedd that led to the burning and looting of the monastery by the forces of Henry III in 1245, though Henry did subsequently offer financial recompense and took the community into his protection. Certainly the close relationship between the rulers of Gwynedd and their Cistercian abbey continued under Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (Llywelyn the Last), who rewarded the monks’ loyalty with grants, and they in turn gave him £40 for his kindness. In 1280 the General Chapter of the entire Cistercian Order, at the request of the abbot of Aberconwy, admitted Llywelyn’s brother, Dafydd, and Dafydd’s wife Elizabeth, into the special prayers and confraternity of the order. It was at the abbey that Llywelyn surrendered to Edward I of England in 1277, and in 1283, in his final campaign in Wales, Edward used the abbey as his headquarters. He decided that the site was just what was needed for his new castle and borough – symbols of his conquest of Gwynedd – and the monastery, except for the church, was demolished. This became the parish church of the borough in 1283/4 (see figure 1).

The monastic community was relocated to a site in the valley of the River Conwy and henceforth known as Maenan. The General Chapter of the order gave its consent, but stipulated that inspectors appointed by it should approve the site and resources that had been offered. Building seems to have been well underway when Edward I and his queen visited in March and again in October 1284, and we may suggest that their visits were connected with the beginning of conventual life at Maenan. Shortly afterwards Maenan, along with other Cistercian abbeys, was compensated for damages sustained in the wars, in Maenan’s case to the tune of £100. Edward seems to have taken a personal interest in the abbey, making further gifts – nearly £77 in 1291 – for the completion of the building work. The monks were also in possession of substantial estates, including arable granges on Anglesey. However, the abbey seems to have been frequently in financial difficulties in the fourteenth century. In 1344, for instance, it was in debt to Italian merchants from Florence, and in 1346 to the Black Prince. At the time of the 1379 Poll Tax there were just an abbot, a prior, and four monks.

1. Aberconwy Abbey: Rood Screen, Church of St Mary and All Saints, Conwy (c.1497–1501).

It is clear that the abbey was implicated in the revolt of Owain Glyn Dŵr at the beginning of the fifteenth century. Abbot Hywel was outlawed in 1406 for siding with the rebels, though pardoned in 1409, and as late as 1448 and 1449 the abbey was claiming still to be suffering the consequences of the aftermath of rebellion, with chalices, ornaments, books, and vestments depleted or lost. The monks must have made their case, for they were excused payments due to the English king. A little is known of the later abbots of Aberconwy. Reginald ap Gruffudd ap Llywelyn ap Gruffudd occurs in 1458, and nearly thirty years later, in 1482, the General Chapter appointed two English abbots to enquire into the yearly pension allegedly paid to his son, Dafydd, and into a certain house belonging to the abbey, which Dafydd’s mother enjoyed. In 1484 headship of the abbey was disputed between Abbot David Winchcombe, who went on to be abbot of Cymer and then of Strata Florida, and Abbot David Lloyd, who seems to have had the support of King Richard III and who was successful in taking the post at Maenan. Lloyd may have been the abbot who was killed falling from his horse in 1490; certainly he was the subject of poems by two of the Welsh bards, who praised his learning and his generosity. Another man named Dafydd, Dafydd ab Owain, previously abbot of Strata Marcella, became bishop of St Asaph in 1503 and was allowed to hold his bishopric with the abbacy of Aberconwy. Two brothers ruled the house in the sixteenth century: Huw ap Rhys between 1526 and 1528, and Richard ap Rhys as last abbot from 1535 to 1537. The house was dissolved in March 1537. Written evidence suggests that the buildings were swiftly demolished, materials being used, for instance, for repairs of the castle and others buildings in Caernarfon.

BUILDINGS AND MONUMENTS

The site of the abbey was a restricted one, encircled by the River Conwy, the coast, and the mountains. The former abbey church of Aberconwy assumed parish status as the church of St Mary, Conwy, after the removal of the monks to Maenan. It was largely rebuilt in the late thirteenth century to contain a nave of four bays, a south transept, an aisleless chancel, and tower. Some fabric of the former monastic church is preserved in the east and west walls. It is possible that the present church represents only the nave of the Cistercian church, though Lawrence Butler suggested that it contains the complete original church. Robinson has demonstrated that the current parish church is similar in length to the nave of Strata Florida, mother house of Aberconwy, and inclines to the view that the parish church may indeed be the successor to the nave of the Cistercian church, though with the patronage of the rulers of Gwynedd it is unlikely to have remained incomplete until the 1280s. There are scant remains of the monastic buildings.

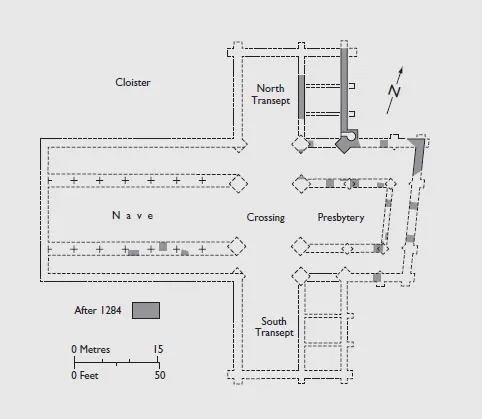

There are now no standing remains at Maenan. A house was built over the west range after the closure of the abbey, and this was replaced by a mansion in the mid-nineteenth century, which subsequently became a hotel. Excavations to the south and south-west of the hotel in 1968 recovered something of the ground plan of the late thirteenth-century church.

2. Aberconwy Abbey (Maenan): Ground plan.

Bryan 1999; Burton 2007; Burton and Kerr 2011; Butler 2004; Hays 1963; Robinson 2006a; Stephenson 2002, 2013; Williams, D. 1990, 2001.

ABERGAVENNY

BENEDICTINE PRIORY

Dedication: St Mary

Diocese: Llandaff

Grid reference: SO30091411

Old county: Monmouthshire

Local authority: Monmouthshire

Ownership and access: public access to the church, which is in the ownership of the Representative Body of the Church in Wales

HISTORY

THE PRIORY OF St Mary, Abergavenny, was one of a number of Benedictine houses in South Wales to be founded in the wake of the coming of the Normans. Its origins lay in a grant made by Hamelin de Ballon (Barham) to the French abbey of St Vincent du Mans. Hamelin had been granted the lordship of northern Gwent, including the castle of Abergavenny, by King William II, and with his brother, Winebald, lord of Caerleon, he exercised considerable power in the region. It was not until the reign of William’s successor, Henry I (1100–35), however, that Hamelin granted to the monks of Le Mans ‘from the subsistence with which he has been endowed by his lords William and Henry, kings of the English, in England and Wales’, tithes and lands, ‘his castle called Abergavenny, with the church and chapel of the castle’. Thus it was that from its very beginning the priory of Abergavenny was closely associated with the castle of the Norman lords. To make clear how sacred his gift was Hamelin placed his charter on the very altar of the abbey church of Le Mans. In addition to the castle chapel, which would have housed the monks while their monastery was in the process of construction and which they were probably intended to serve, Hamelin granted land for the monks’ dwelling places, a bourg (township), water for a mill, and rights to fish in the river, as well as a church. Hamelin and Winebald added further churches and tithes, making Abergavenny’s endowment a considerable one. Despite the part played by both brothers it was Hamelin whom later generations of monks regarded as their founder.

At first the small monastic settlement established at Abergavenny functioned as a cell of the French abbey, that is, there would only have been a few monks there to administer the local property on behalf of Le Mans. However in the reign of Henry II (1154–89) the then lord of Abergavenny, William de Braose, further increased the endowments of the monks so that full conventual life could be sustained there. His generosity to the monks meant that he and later patrons could expect a more substantial number of monks – usually thirteen – to carry out the round of liturgical services, rather than just being an economic unit. In 1195 Henry, prior of Abergavenny, was elected as bishop of Llandaff. Despite this distinction, the priory continued to be a dependency of Le Mans, and the Abergavenny monks were required to pay the mother abbey the yearly sum of £5 7s as a mark of their dependent status. The abbot of Le Mans, or a proxy appointed by him, would have been expected to visit the priory from time to time in order to ensure that the standards of observance were being maintained. From 1204, when the county of Maine was lost to the English king, this would have been more difficult.

It was not just the abbot of Le Mans who would have been concerned about the state of monastic life at Abergavenny. This was also of considerable interest to Abergavenny’s patron (since a poorly run monastery might reflect badly on a patron) and to local churchmen. John de Hastings, the priory’s patron, took action when in 1319 he discovered things that troubled him. So concerned was he that he requested Pope John XXII to instigate reform at the priory. And so the following year Bishop Adam de Orleton of Hereford was appointed to conduct a visitation. On his arrival, accompanied by the bishop of Llandaff and other clergy, Bishop Adam summoned the prior and monks to appear before him for questioning. He found that there was a considerable discrepancy between the size of convent that the priory’s resources (around 240 marks, or just over £158) could sustain – which he estimated would be thirteen monks – and the actual number, which was just five. Such a fall in numbers could not be excused in terms of finance.

3. Abergavenny Priory: The fifteenth-century Jesse Tree.

What made matters worse ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of maps

- List of images

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Foreword to Gazetteer

- Gazetteer of Abbeys and Priories

- Glossary

- Bibliography