![]()

1 INTRODUCTION

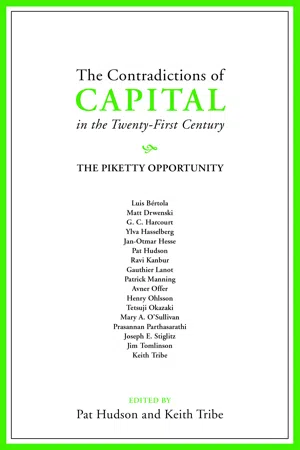

Pat Hudson and Keith Tribe

Thomas Piketty’s Le Capital au XXIe siècle was first published in Paris during the summer of 2013. On the appearance of an English edition in March 2014 it became an international blockbuster, being quickly translated into German, Spanish and Chinese. Sales of all copies by January 2015 were 1.5 million and rising, fuelled by popular concern about growing income inequality and the links between inequality and global economic instability. Thanks to Piketty, and to his large transnational team of colleagues, together with a spate of recent books on global wealth and income disparities, distribution is back at the centre of our concerns.1

PIKETTY’S PROMISE

In light of the mass of new comparative data contained in Capital in the Twenty-First Century, and in associated publications and appendices, it is clear that some common long-run trends in inequality across the developed world had not been sufficiently recognized. In particular, Piketty emphasizes the notable increase in income-generating wealth of top income earners in recent decades, together with rising pay. His study of top incomes, and their genesis, has unsettled the widely held assumption that capital’s share in national income (via interest, dividends and capital gains) would always necessarily revert to a long-run constant. The social concentration of wealth through inheritance and its role in cumulatively ratcheting up incomes, and thus further increasing wealth in the top 10 per cent or so of the population, is now in the spotlight. It is this that underpins Piketty’s dire prediction that, in the absence of fiscal and other measures to arrest the trend, things can only get worse. The new patrimonial class will increasingly engineer the political and legal process to further their economic interests, the rewards to merit and education in society will break down, and crises will ensue across the social democracies within a few decades.

Following the work of Simon Kuznets in the early 1950s, economists had generally assumed that modern economic growth would in the long run reduce the gap between rich and poor. In the early post-war years it was relatively easy to accept the inverted U-shaped curve of income distribution that Kuznets had identified for developed economies. Though based on flimsier evidence than we have today, tax and income data for the first half of the twentieth century, and mainly from the US, supported his argument that early industrial capitalism may, at first, have created greater economic and social inequality but that this was negated as capitalism matured, creating a more progressive balance of the rewards to labour compared with the shares of national income accruing to profits and rents.2

During the twentieth century there was a long and sophisticated tradition of writing about the ills of inequality and how to deal with it3 but economists of the era following Kuznets showed little interest in the matter. Kuznets’s thesis was presented during the period when neoclassical economic thinking was in the ascendant, and it was widely supposed that inequality was a necessary spur to aspiration and endeavour. Most economists of the period also assumed that, as economies tended towards stabilization at (or near) full employment, working people would earn what their skills and education entitled them to. As long as the engine of growth, sparked by continuous technical change, was given the freedom to keep going, the trickle-down effects of the rewards to capital would permeate throughout society. Hence the goal was growth, growth and more growth. And the main concern of economists was to identify the sources of economic growth, and how to increase and sustain it. Distribution was often seen as a pernicious distraction. Hence the statement of the Nobel Laureate Robert Lucas, writing as recently as 2004, that: “Of the tendencies that are harmful to sound economics the most seductive and … the most poisonous is to focus on questions of distribution.”4

The rationale for the market liberalization measures introduced during the 1980s and 1990s was faster growth, a view especially influential in the UK and the US. Instead, growth slowed, economic instability increased and the top layer of Western societies benefitted disproportionately from deregulation and privatization. Economists struggled to explain these contrary results. Then the global financial crisis of 2007–9 – accompanied by widespread protests about the iniquities, as well as the inequities, of liberalized globalization – unsettled popular faith in the core tenets of conventional economic theory. This was at last a real “legitimation crisis of capitalism”, to borrow a phrase from German Marxists of the 1970s. The financial crisis undermined any idea that bankers, financial experts and corporate executives were doing sufficiently responsible and socially useful work to justify their explosively high remuneration. Furthermore, the dominant voices among academic economists had been unable to predict or even identify the causal forces at work during the crisis.5 This was the “Piketty moment”. By moving away from a preoccupation with economic growth and its determinants, by highlighting the large and growing gap between the wealth that societies have at their disposal and the human utility it generates, and by undermining the dominant view that free market capitalism spreads increases in wealth throughout society, Piketty promised a new perspective on the ills of modern economies.

In the reviews and discussions that followed the publication of Capital in the Twenty-First Century, major inconsistencies in Piketty’s comparative data (arising inevitably from varied, complex and incomplete taxation and other records available in different national contexts) have been highlighted, alongside problems in his definitions of capital and his model of the dynamics of accumulation. He has been particularly held to account for neglecting the overriding importance of an array of political economy and technological factors at play in determining the vagaries of income and wealth distribution across countries and over time, especially since the 1980s, although he has clarified and contested this in subsequent publications.6 His major thesis – that inequality in the long term is driven not by politics, technology, financialization, globalization or the specialization of economies but by rates of return on capital that exceed the level of economic growth – leads him to concentrate, in policy terms, largely upon a narrow range of radical fiscal solutions that critics have termed impractical (as indeed has Piketty himself) or naive. The aim of this collection of essays is to move on from this phase of endorsement or criticism of particular aspects of Piketty’s argument and refocus attention on the larger questions he has raised.

CONSTRUCTIVE DIALOGUE

While criticism of Piketty’s theory, method and data analysis can be found in this volume, in every case the purpose is constructively to highlight the complexities of aggregate cross-national comparative work of this kind using long-run time series data based on sources that are both country specific and temporally specific and are therefore hard to compare. We consider Piketty’s arguments about wealth, capital and inequality with reference to the variability of political, historical and global contexts. Finally, we consider the opportunity that his work creates for rethinking some of the basic assumptions and methods of economics and of economic history.

First of all, attention is given to some foundational analytical concepts and models that are central to Piketty’s work, in particular those concerning capital, wealth, inequality, money and real estate. The national-level sources and context of Piketty’s data are then considered. Beginning with aspects of the fiscal and demographic history of France, we move on to consider how the specific developmental features of his other major sources (for Germany, Sweden, the US and Britain), together with the fiscal and welfare policies of these countries, might modify Piketty’s general arguments regarding long-term movements in capital, wealth and income. In these chapters we go back to Piketty’s definitions and data sources, examining the possibilities and limitations thrown up by historical national statistics and their intersection with the social and political history of the countries concerned.

Four shorter surveys then sketch out how Piketty’s findings and thesis might bear on economic development outside the main twentieth-century Western industrial economies. These “global commentaries” consider the history of inequality in Latin America, Africa, Japan and India in the light of Piketty’s work and ideas, suggesting that more attention be paid to cultural specificities and to the long-term impact of colonialism, resource depletion, unequal trade, patterns of primary, secondary and tertiary specialization, international financial flows and the power play of world politics. The book concludes with discussion of the dominant goals, measures and theories of growth and development that have been unsettled by Piketty’s work, and considers their future prospects. Throughout, the assumption is that Piketty has provided an opportunity to re-examine the purposes and the jaded tool kit of current mainstream analysis in economics and economic history. It is in this spirit of dialogue that all contributions have been written.

A WORLD OF DIVERSE TRAJECTORIES

In the early nineteenth century European economies broke free of a number of political, economic and social constraints. Absolute monarchy gave way to republican and parliamentary regimes that, in the course of the century, reconstructed conceptions of equality and human rights. Economies that had for millennia been shackled to the agrarian cycles of dearth and plenty began a re-orientation to the rhythms of manufacture and commerce. Populations that had long been held in check by disease, warfare and food shortage began a secular increase, shifting away from rural occupations to urban employments. The rate at which this happened varied greatly from one country to another; England was already considered the model by the 1830s, and it was a Frenchman, Adolphe Blanqui, who in 1837 coined the idea that an “Industrial Revolution” was under way in Britain.7

But while England did exemplify the possibilities of economic and social change, it represented a developmental path that no other economy followed closely. Although Britain rapidly became a highly urbanized economy whose population was largely fed by imports paid for by its manufactured exports, one hundred years after Blanqui had written Europe still for the most part lived off its own agricultural produce. Germany, the most industrialized of Continential European economies, had in the 1930s around half of its population in rural areas.

If we, along with Piketty, add the US into this picture, matters become even more complicated. For almost a century after its foundation the first large-scale modern republic harboured the most profound inequality possible – that between free human beings and slaves – and even after the Civil War systematic racial discrimination was underwritten by statutes that prevailed for another hundred years. The northern states moved to a different rhythm, attracting successive waves of migrants from Europe and, in the wake of the Civil War, experiencing rapid westward territorial expansion combined with the rampant industrialization of the Gilded Age. Remote from international politics throughout the nineteenth century, the stance of the US changed with its involvement in the First World War: a war that scarred the major Western European economies but provided the platform upon which international American supremacy in the twentieth century was built. This was dramatically reinforced by its role in the Second World War, a conflict that was also a watershed across the developed world in transforming ideas about the role of the state, national accounting, macroeconomic management and welfare provision. The rate at which this happened was not, however, uniform: Japan and West Germany, both occupied by American forces, proved most resistant to many of these ideas, despite contemporary critiques of American cultural imperialism.

Even sketched out roughly in this way, it becomes obvious that the core economies upon which Piketty’s analysis of wealth and inequality is based – France, Germany, Sweden, Britain and the US – have, since the early 1800s, diverged from each other as much as they have converged along a common developmental path. And once attention moves beyond these countries to the rest of the world, it becomes plain that any talk of common “global trends in inequality”, to say nothing of their causation, forcibly aggregates a diversity of conditions and histories that escapes easy generalization.

This is not of course to say that trends in inequality do not exist, nor that the many dimensions upon which inequalities can be registered are simply a reflection of the human condition. Economists, in seeking to make sense of the world, naturally turn to simple models – in most cases growth models built around inputs of “capital” and “labour” – through which aggregated data can then be run to identify relationships and networks of causation. The simplicity of the models dictates the use of simplified aggregates: in its most reductive form, historical data often becomes merely the meat for an economic mincing machine. In this way aggregate trends are produced that reflect the pace and structure of development in none of the countries from which the data sets have been drawn: this is the danger to set against the great promise and insight of Piketty’s work.

Most economists today are resolutely present-centred, viewing the recent past through current preoccupations, and imposing these preoccupations upon stylized versions of the longer run. That such self-confidence is ill-founded is now widely recognized. The appropriate response is not to replace “theory” with “history” but to look for better ways to link theory and history together. This is undoubtedly Piketty’s aim, and the wealth of new and much-needed data that he provides, covering several regions of the world over two centuries, is a path-breaking achievement of historical reconstruction.8 For a work of economic history, Capital in the Twenty-First Century has a refreshing absence of complex causal models and statistical regressions. Piketty carefully teases out common trends and national differences. In its methodological sympathies, at least, his work might be seen as a return to the aims and methods of historical economics: not narrow empiricism, but empiricism with a purpose – an “analytical historical narrative”, as Piketty himself terms it.9 His “fundamental laws” of capitalist development might, in this light, be seen as an empirical generalization derived inductively from the mass of data assembled.10

That said, Piketty is an economist trained in the 1990s, sharing many of the reflexes of his peers. The concepts and terminology that he routinely employs have long and much-debated histories that he barely explores, and his causal thesis remains consciously embedded in an outdated neoclassical orthodoxy. His comparative national approach, rooted in close study of five major Western economies, inevitably sidelines the insights that might derive from a more connective or global historical analysis. And his emphasis upon common paths and experiences of development driven, in the last instance, by a common mechanism diverts attention from potentially more important, more varied and perhaps more tractable determinants of inequality. Thus, although Piketty’s book is a landmark and a watershed for both economics and economic history, fully deserving of its huge readership and acclaim, it is justified to state that “Despite its great ambitions, his book is not the accomplished work of high theory that its title, length and reception (so far) suggest.”11

Nevertheless, thanks to Piketty, to his immediate colleagues and also to the work of Bourguignon, Galbraith and Milanovic in particular, the transformation and distribution of global wealth in the last 100 years, and the links between inequality and global economic and political stability, now sit at the top of the social science agenda. If we are to understand the implications of this observation, we must use Piketty as a springboard to debate, but also to move beyond aggregated data sets to the institutions that produced the data, and the tasks that these institutions were set – new systems of taxation, state and private pensions, welfare benefits, unemployment, housing finance – in the emergent nation states of the nineteenth century, and in the more “mature” nat...