![]()

1.

The corruption challenge

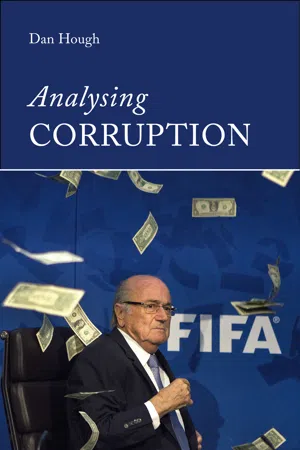

Corruption, so it seems, is everywhere. One indicator of this is the amount of coverage that it gets in the popular press. In 2015, for example, the word “corruption” appeared 1,240 times in UK newspaper article headlines. “Fraud” was even more prevalent, appearing on 4,177 occasions. The word “bribery”, meanwhile, came up a mere 264 times.1 The types of cases covered were wide, varied and often bewildering. On one day alone in the UK (24 November 2015), The Independent was analysing how the Vatican was putting reporters on trial who had previously uncovered corruption cases in its midst, while The Times was reporting a story about an apprentice jockey who was facing a ban from horse racing on account of deliberately riding to lose.2 At the same time, The Herald was discussing Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta’s anti-corruption reforms, while The Guardian was analysing FIFA’s alleged corruption problems.3

The world of academia is also covering issues of corruption in ever more depth and breadth; a search in mid-2016 for the term “corruption” on JSTOR, the digital library of academic publications, revealed no less than 169,941 journal articles in which corruption was mentioned. “Fraud”, meanwhile, appeared in 105,144 articles, and “bribery” came up on 22,971 occasions. While not all of those articles will have been on corruption as it is understood in the social sciences, it is still clear that the term, and concepts that are closely linked to it, are on a lot of people’s minds.

There are plenty of good reasons for that. In 2014, the World Economic Forum estimated that $2.6 trillion was being lost yearly to corruption, while the World Bank has claimed that $1 trillion is paid out every year in bribes (OECD 2014: 1). In 2015, Global Financial Integrity, a Washington-based non-governmental organization (NGO), bemoaned the fact that between 2004 and 2013 developing and emerging economies lost $7.8 trillon in illicit financial flows (Kar & Spankers 2015). Furthermore, it is not just in the most impoverished parts of the world that corruption takes place; as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has noted, it has been estimated that between 5 and 10 per cent of the budgets of Medicare and Medicaid, the American health care programmes, go missing on account of corruption (OECD 2014: 3). In Europe, meanwhile, one report has claimed corruption could be costing EU members upwards of €179 billion (Hafner et al., 2016). The nature and extent of corruption might vary from place to place, but nowhere is exempt. The numbers are by definition rough and ready, and they should in many ways be treated with a significant degree of caution, but they are still an indication of the costs that pervasive corruption brings with it.4 It is no wonder that corruption has become one of the key public policy challenges of our times.

Widely discussed though corruption now is, we still know surprisingly little about what works in the fight against it. Indeed, the concept itself remains hugely contested. However, that has not prevented scholars and practitioners from creating a wide array of anti-corruption tools. In the international arena, for example, there are conventions, treaties and multilateral agreements (see Table 1.1). A total of 140 states and territories have signed the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), while 41 countries are signatories to the OECD’s anti-bribery treaty. International organizations such as the Council of Europe (CoE), the Arab League and the African Union have all created tools for helping (and at times compelling) their member states to take the fight against corruption forwards.

Furthermore, national governments, business representatives and civil society organizations have come together to create thematically focused international anti-corruption initiatives. To give just three examples, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) looks to try to bring greater transparency and openness to the notoriously opaque business of natural resource extraction; the Maritime Anti-Corruption Network (MACN) seeks to bring businesses together, with a view to eliminating corruption from the maritime industry; and the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) tries to coordinate international anti-money laundering efforts.5 Such agreements are broad-ranging in scope and substance, and – unsurprisingly – have had mixed results. At the domestic level, too, there have been a plethora of initiatives that cater for specific sets of national and local challenges. We see much-vaunted domestic anti-corruption plans launched in places such as the UK, along with global open data and transparency initiatives. We have even seen game shows such as Integrity Idol develop in places like Nepal.6 The world is not suffering from a lack of anti-corruption initiatives.

Table 1.1 The main international conventions and agreements that aim to tackle corruption.

All information correct at time of writing.

This book can neither outline all of these different approaches in detail nor claim to come up with remedies that undoubtedly work everywhere. Tackling corruption is clearly not that simple. What this book can do is analyse what might work as well as what certainly will not and why. It can also explain how anti-corruption thinkers can learn from the (many) mistakes of the past. To misquote Albert Einstein, making a mistake is not the issue: the skill is in not making the same mistake twice. This book, in other words, analyses why so many anti-corruption policies fail, with a view to drawing lessons as to which ones might plausibly work in the future.

While the aim is to keep the analysis of corruption focused on the real world, this book also has a theoretical focus. Over the past 20 years, there has been considerable debate about not only how best to conceptualize corruption, but also what causes it, what its effects are and ultimately what (if indeed anything) should be done to counteract it. There have been interesting and thoughtful contributions from scholars coming from a wide range of theoretical and disciplinary traditions, and this book tries to do justice to at least some of that diversity. Lawyers and legal scholars, for example, instinctively start with legal frameworks and legal processes. Their focus on issues of legal best practice, the impact of anti-corruption laws on company and individual behaviour and the challenges of law enforcement have helped governments trying to craft appropriate anti-corruption legislation. Economists, meanwhile, have tended to place a more obvious stress on the incentives that lead to corrupt behaviour. They have subsequently been vocal in suggesting policies and institutional frameworks that might conceivably prevent corruption from occurring, but they are less keen to get involved in complex debates about what corruption actually is. Anthropologists have faced the very opposite problem. Their work remains heavily context specific and rich in detail, but they have traditionally remained suspicious of anything that looks like a generalized theory of corrupt action. All of these approaches, despite their relative weaknesses, contribute something to the debate.

In a practical sense, this book looks at the corruption challenges in both the developed and the developing world. It will analyse international attempts to tackle the problem (see Chapter 7) and unpack and scrutinize the most prominent national (and, indeed, subnational and local) anti-corruption initiatives (see Chapters 8 and 9). A wide range of real-world examples are also used to illustrate the main arguments made.

ANALYSING CORRUPTION

The book centres around three simple questions: what is corruption, what causes corruption and what works in the fight against corruption? The analysis presented in the substantive chapters covers plenty of ground, but these three questions remain at the core of the book. Chapter 2 starts by illustrating that the analysis of corruption has come a long way since it was first discussed in earnest by the likes of Plato and Aristotle. For those thinkers, corruption was more about moral decay than it was about abusing public power for private gain. Indeed, corruption was often understood as being about aberrations that took a polity away from a non-corrupt state of being. The emphasis was much less on the behaviour of individuals fulfilling their daily duties, and much more on bigger questions of community and statehood.

Over time, that focus changed. The international consensus now places individual behaviour at the centre of much corruption thinking. Corruption (in the Western world, at least) has come to be seen as a process via which errant individuals behave inappropriately to enrich themselves. In the mid- to latter part of the twentieth century, this also led to corruption, often indirectly but sometimes quite explicitly, being rather patronizingly understood as a developing-world problem. The West had systems, so the often-unspoken argument went, which stressed a neutral, meritocratic bureaucracy that put a premium on fairness, equality before the law, efficiency and competence. This ensured that when corruption appeared it was nipped quickly in the bud. Developing countries did not enjoy the merits of a Weberian bureaucracy and subsequently had to deal with corruption on a much larger scale. A neat and tidy argument to make in an era of colonial thinking; not such an effective one if you really want to understand the nuances of corruption across different polities. Time has moved on.

It was the stream (which soon became something of a torrent) of corruption scandals that engulfed many Western states through the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s that really brought corruption to the forefront of people’s minds. Scandals such as Watergate in the US, the Flick Affair in Germany, Back to Basics in the UK and Tangentopoli in Italy indicated that the West itself might have corruption problems that needed dealing with.7 In the 1990s, the international policy community also “discovered” corruption as a policy problem, and began talking about how to counteract it. Furthermore, groups of economists, anthropologists, psychologists and political scientists also began to confront the serious methodological challenges that have traditionally plagued corruption analysis. The quality of data available to analysts of corruption improved (see Chapter 4), and approaches to the subject subsequently became more rigorous.

All of these developments aside, the moral focus that occupied much of the early work on corruption has not vanished. Working out what is morally and ethically acceptable remains important in helping us understand precisely what corruption is. The fact that moral standards differ ensures that these definitional debates can at times appear to be never-ending, but that cannot be an excuse for hastily glossing over them. When trying to pin down the notion of corruption, one is inevitably drawn into philosophical discussions that do not easily lend themselves to empirical answers. This also affects how (and, indeed, whether) we go about tackling corruption (see Chapters 7–9). While it is therefore tempting to view corruption as something that is always “wrong” or “bad”, Chapter 2 illustrates that there are still a number of moral and ethical challenges that bring this one-dimensional understanding of corruption into question.

DEFINITIONS AND MEASUREMENTS

Chapter 3 brings the discussion of what corruption is right up to date. As noted in the previous paragraph, defining corruption can be both difficult and frustrating, yet it is something that has to be done. To use an analogy, a patient cannot simply walk into a doctor’s consulting room and ask for some drugs to make herself better. For starters, the doctor would not have any idea what drugs to give her; the remedy for breathing problems is going to be altogether different to that for tennis elbow. The doctor needs to ask the patient to explain what is wrong, to outline her symptoms, to define the problem. Only then can the doctor understand the nature of the problem and begin to think about the ailment’s particular causes. Corruption and anti-corruption need to follow the same logic, and a fundamental part of that logic is defining right at the beginning what exactly the problem is.

Chapter 3 argues that, in essence, there are four contemporary types of definition: (a) those that are based around legal understandings of corruption, (b) those that centre around an abuse of entrusted power, (c) those that involve business transactions and, finally, (d) what has recently come to be understood as “legal corruption”. Approaches that take the law as their starting point begin, unsurprisingly, with a given state’s legal framework. This has the advantage of giving the corruption analyst clear markers as to what is and what is not corrupt. It brings much-needed clarity to what can become a confusing debate. However, public servants are usually well aware of what the law says. They also know that breaking it normally leads to trouble, so they generally do not do it. Rather, they may well find ways of bending the law, or skillfully circumventing it, to get what they want while legitimately claiming they have done nothing wrong. Furthermore, laws differ across both time and space; what might be considered corrupt in contemporary politics may not have been seen as that a relatively short time ago. Plus, what the law considers corrupt in one country may not be seen as any such thing in other (ostensibly similar) polities. There is, therefore, a danger that using the law as your benchmark can cause as many problems as it solves.

Many analysts subsequently look to bring context back into the discussion. They do so by...