eBook - ePub

How to Keep a Competitive Edge in the Talent Game

Lessons for the EU from China and the US

- 104 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

How to Keep a Competitive Edge in the Talent Game

Lessons for the EU from China and the US

About this book

BY 2020, the global map of higher education will be completely redrawn, and by 2030, China is expected to emerge as the world's largest source of brainpower. The European Union should not necessarily view this development as a threat, but rather it can be seen as an opportunity for the EU to become more competitive in attracting foreign human capital. The quality of human capital in the form of university graduates is well-developed in the EU, although there remain stark differences between the member states. EU universities have not managed to penetrate the premium university rankings, with the exception of those in the UK, but their overall performance is comparatively high.

This book compares tertiary education in the European Union, the United States and China with the aim of evaluating how the EU as a region fares with respect to the US and China, how to improve higher education in the EU and how to secure its stock of human capital. In the process, we identify a number of game-changing factors that affect higher education. These notably include how digital technology is integrated into education, how education relates to employment and how university institutions are governed. Viewed intra-regionally, Europe is making progress in developing its talent pipeline. But if we take a step back and compare the performance of higher education in the EU with that of the US and China -- and how it is likely to perform in the future -- there are important lessons to be learned that will allow Europe to sustain prosperity and growth and secure its long-term well-being and quality of life.

This book compares tertiary education in the European Union, the United States and China with the aim of evaluating how the EU as a region fares with respect to the US and China, how to improve higher education in the EU and how to secure its stock of human capital. In the process, we identify a number of game-changing factors that affect higher education. These notably include how digital technology is integrated into education, how education relates to employment and how university institutions are governed. Viewed intra-regionally, Europe is making progress in developing its talent pipeline. But if we take a step back and compare the performance of higher education in the EU with that of the US and China -- and how it is likely to perform in the future -- there are important lessons to be learned that will allow Europe to sustain prosperity and growth and secure its long-term well-being and quality of life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access How to Keep a Competitive Edge in the Talent Game by Christal Morehouse,Matthias Busse in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. INTRODUCTION

This book examines education at the university (or tertiary) level in the European Union, the United States and China. The aim of this analysis is to determine how well the EU as a region performs with respect to the US and China and how to improve higher education in the EU – and with it the EU’s stock of human capital.

The skills, abilities and innovative capacity of European citizens are vital to competitiveness of European economies. Data from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) have repeatedly shown a positive correlation between high levels of tertiary education and employment, earnings, innovation and economic prosperity. We no longer live in an industrial age in which amassing financial capital alone is enough to attract the manpower and – most importantly – the brainpower that economies need to create jobs and growth. Some have suggested that our current period could best be dubbed the ‘talent era’, in which the balance of economic strength might be tipped in favour of those countries that are strong innovators. And for innovation, one needs a healthy stock of human capital.

The so-called ‘brain race’ is fuelled by universities; the public and private sectors must also foster the development of skills. Global talent mobility is part of the international talent balance, as is the employability of graduates. It is still unclear which nations will emerge as the global leaders in the coming decades. The world is changing rapidly, and a lack of progress can spell decline. In the ‘brain race’, countries will have to run to stand still and they will have to progress very quickly if they want to emerge as global talent leaders.

The EU has recognised the role of tertiary education as a benchmark for overall prosperity and long-term economic growth in Europe. The Europe 2020 Strategy (European Commission, 2010a),1 set the goal of increasing the tertiary graduation rate among 30- to 34-year-olds to 40%. The EU has also established scoreboards (such as the EU Innovation Scoreboard and the EU Higher Education Mobility Scoreboard) in a number of areas. These scoreboards include information on how Europe’s most precious resource – human capital – is changing. Viewed intra-regionally, Europe is making progress in developing its talent pipeline. But if we take a step back and set the EU in the context of how the US and China are doing – and are likely to do in the future – several lessons can be drawn. The EU must remain competitive in the emerging knowledge-based global economy by strategically growing its talent pipeline. With this aim in mind, the EU and its member states should:

- conduct in-depth research into the state of human capital in the region,

- create incentives to counteract a depletion of skills and to develop talent,

- make investments that increase the positive impact of competence on economies and societies, and

- increase the relevance of tertiary education for the labour market and life chances.

Such elements could be thought of as contributing to ‘virtuous circles’ of talent and innovation to sustain prosperity and growth.

The remainder of this report is organised around four chapters. Chapter 2 offers a comparative analysis of the performance of the EU, the US and China in higher education and assesses the quality and quantity of education delivered by their respective institutions. Indicators, such as the number of tertiary degree holders and the reputation of universities, are examined in a comparative manner. This chapter considers past performance and also uses data on upper-secondary education (e.g. performance of future tertiary classes) to project, how one might expect higher education to ‘perform’ in the coming years.

Chapter 3, entitled “Private and public funding of higher education in the EU, the US and China”, investigates investment in education in the EU, the US and in China. It not only examines the aggregate funding for institutions of higher learning, but it also breaks down the composition (private and public) of this funding. Like chapter 2, this chapter explores past trends and consider how changes in funding could affect higher education in the coming years.

Chapter 4, entitled “Game-changing factors in innovating higher education”, explores the impact of technology, the employability of skills, as well as university governance on tertiary education.

Each chapter of this report distils policy recommendations from the analysis. The concluding chapter 5 draws together the chapter recommendations and places them in a broader policy context. Four sets of recommendations are addressed to EU policy-makers with the aim of improving higher education in the EU and the EU’s stock of human capital to ensure its continued competitiveness in the global economy.

Footnote

1 Adopted in 2010, Europe 2020 was the EU's growth strategy for becoming a “smart, sustainable and inclusive economy” over the next decade, in the hope that these three mutually reinforcing priorities would help the EU and the member states achieve high levels of employment, productivity and social cohesion.

2. COMPARATIVE PERFORMANCE OF THE EU, THE US AND CHINA IN HIGHER EDUCATION

In an ever-smaller world, how countries perform in relation to one another is an important indicator of their future prospects for economic and social development. This chapter compares tertiary education outcomes in the European Union, the United States and China by closely examining the quantity and quality of higher education. Because upper secondary schools ‘feed’ into the university system, the quality of their performance is also taken into account. Analysing pre-secondary education performance and its impact on human capital would go beyond the scope of this report. It is nevertheless acknowledged that investment in education at an early age yields a high return to the quality of human capital (Carneiro & Heckman, 2003).

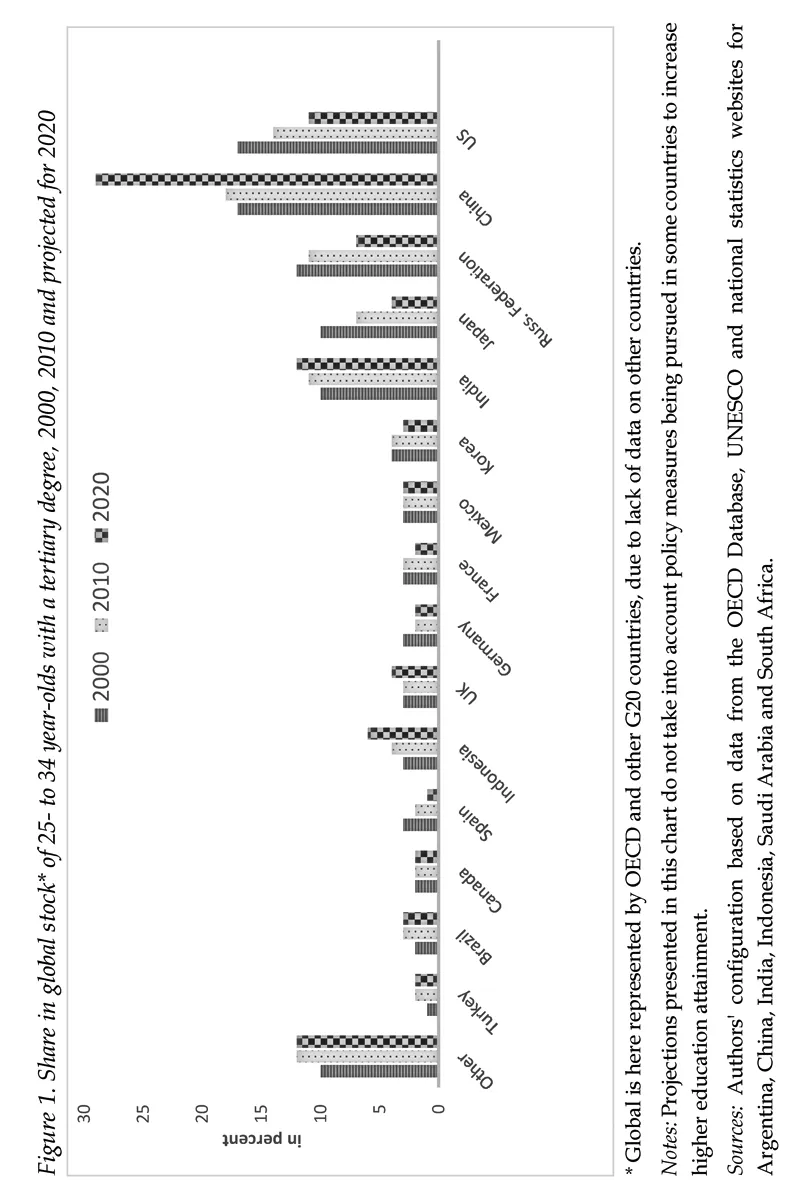

Concerning the quantity of education, China is making rapid progress towards becoming a hub for highly educated persons. According to the OECD (2012a), “if current trends continue, China and India will account for 40 percent of all young people with a tertiary education in G20 and OECD countries by the year 2020, while the United States and European Union countries will account for just over a quarter”. Even though a lower percentage of China’s population will graduate from higher education than that of the US and the EU, the sheer scale of China’s population will allow it to dominate the brain pool. China has been investing heavily in its educational systems, and OECD projections for 2020 show that the country could achieve a tertiary graduation rate of 27%, which is below the EU average but higher than the current Italian rate.

The US is far from the global leader in tertiary graduation rates, ranking 12th in the world. Korea ranks first with a tertiary attainment rate among 25- to 34-year-olds of 64% (OECD, 2012a). In 2013, most EU countries had achieved a graduation rate of 37% of 25- to 34-year-olds (Eurostat, 2014a), which falls just under the US rate (43% in 2011) (OECD, 2012a). EU countries that have not yet achieved such a high graduation rate either possess a very efficient system of vocational training, such as Germany and Austria, or are making reasonable progress towards achieving the target. Italy for example, has rapidly increased its national graduation rate in the last three decades.

Concerning the quality of education, there is no international standard for comparing the quality of university student performance. The OECD has been developing a project on the Assessment of Higher Education Learning Outcomes (AHELO), which aims to assess what tertiary-educated graduates in 17 countries and regions know. The AHELO test was designed to evaluate general skills (such as critical thinking, analytical reasoning, problem-solving and written communication), economics and engineering. It is intended to be administered shortly before graduation from undergraduate studies (Tremblay et al., 2012). The project has struggled with the design of its assessment tool and has worked through several consultations with stakeholders to come up with a feasible design.

The performance of upper-secondary students on the well-known PISA test,2 in combination with university reputation (rankings), help define the contours of the quality of tertiary education in international comparisons. Generally EU students outperform their US counterparts in the PISA study. And although the quality of education is thought to vary greatly across China, Shanghai and Hong Kong were the global benchmarks in the most recent (2012) PISA ranking. Regarding the reputation of universities world-wide,3 US universities dominate the top global rankings. In the EU, the United Kingdom stands out as a strong global competitor in the tertiary education sector. Continental Europe, however, lags behind the US and is losing ground to Chinese universities. Germany’s top-performing university (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München) came in, at 55th place, behind China’s top performers – University of Hong Kong (43rd place), Peking University (45th place) and Tsinghua University (50th place). France’s top performer (École Normale Supérieure) was ranked 65th and Spain’s best university (Pompeu Fabra University - Barcelona), at 164th place, came in behind no fewer than five Chinese universities (University of Hong Kong, Peking University, Tsinghua University, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology and Chinese University of Hong Kong). Evidence suggests that China will soon be able to increase its presence in university rankings and – in addition to its domestic talent, its growing economy and the reputation of its universities – attract talent from abroad.

This chapter is based on the following data sets:

- Share in global stock of 25- to 34 year-olds with a tertiary degree in 2000, 2010 and projected for 2020;

- First 4 university degrees in science and engineering by region, 2010;

- Total numbers of first university degrees in engineering, 2000-10;

- Various global university-wide rankings, 2013 and 2014; and

- PISA results, 2012.

2.1 The quantity of education at the tertiary and upper-secondary level

2.1.1 The quantity of tertiary graduates across OECD and G20 countries

The correlation between high levels of education and innovation, economic growth and long-term prosperity is strong. Therefore, the EU must develop a talent strategy in which tertiary education serves as the cornerstone. It has already taken steps to do so. For example, the European Commission’s ‘Europe 2020’ strategy has set a target of 40% for the tertiary graduation rate for 30-34 year olds by the end of this decade. A number of EU member states had already met, or surpassed this benchmark in 2012: Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Ireland, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and the UK. Taken on its own, this appears to be good news, but if we compare the development and projected output of Europe’s strongest producers of tertiary graduates – France, Germany, the UK and Spain – with the US and China, a different picture emerges.

By 2020, the global map of higher education will be completely redrawn. The number of people with a tertiary-level education in OECD and G20 countries is expected to have grown from 91 million 25- to 34-year-olds in 2000 to 204 million (OECD, 2012a). Within 20 years, China will emerge as the world’s largest source of brainpower. This shift is unprecedented in human history, especially when one considers that in 2000, the United States and China were producing the same share of global graduates, 17% each (OECD, 2012a). In 2010 China emerged as the single leader of this cohort. China is expected to become home to 29% of the world’s tertiary-degree holders in 2020 and will dominate the ‘brain game’ quantitatively. In 2020, China will have more than double the share of 25- to 34-year-old tertiary degree holders in OECD and G20 countries, as compared to its closest competitor India (12%). The United States is expected to have the third-largest percentage at 11%.

Both the US and China are pursuing benchmarks to expand their talent pools. Obviously the individual performance of these two countries cannot be measured by their share in the global talent pool, but rather by the size relative to their population. Nevertheless, the changes in the global stocks are crucial in determining where future skilled labour supply will reside. Indeed, China’s progress in increasing the share of its population with a tertiary degree is impressive.

According to the OECD (2012a), it “has quintupled its number of tertiary graduates and doubled its number of tertiary institutions in the last 10 years”. China has a National Plan for Medium- and Long-term Education Reform and Development. It aims to increase the number of its citizens with higher education from 98.3 million in 2009 to 195 million in 2020 (OECD, 2012a). The country’s leadership would like to shift the economy from a labour-intensive one to a knowledge-based economy. Beyond developing talent domestically, China plans increasingly to recruit talent from abroad, using its universities to attract students. In 2009, the US government aimed to help the country become the nation “with the highest proportion of 25- to 34-year-old university graduates by 2020” (OECD, 2012a). To meet this goal, it would need to have 60% of that age cohort graduate by the end of this decade. As countries of very different size compete in the global brain game, smaller countries may face new challenges regarding the advantages and risks of workforce concentration vs. diversification.

Within the EU, the UK is forecast to be best positioned to compete for international students in the future. The country is expected to increase slightly its share of global tertiary graduates in 2020, which is contrary to the trend in other EU countries. Models for predicting international student mobility use indicators such as: income per capita, demographic change, domestic and international higher education participation rates, as well as the perceived quality of education and employment prospects for the degree acquired (Böhm et al., 2004). Language is also thought to be an important factor for international students when they choose an international destination. International students often prefer courses taught in English.

Recommendation

Measuring the quantity of education in global comparison

The EU’s tertiary education benchmark, embedded in the Europe 2020 strategy, aims to increase the EU’s tertiary graduation rate among 30- to 34-year-olds to 40%. This benchmark should be reported on in global comparison, and the progress of EU member states should be discussed regularly by the responsible ministers from...

Table of contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Foreword

- Preface

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Comparative performance of the EU, the US and China in higher education

- 3. Private and public funding of higher education in the EU, the US and China

- 4. Game-changing factors in innovating higher education

- 5. Policy recommendations for the EU: Learning from China and the US

- References

- Annex. Members of the CEPS Task Force and Invited Speakers