- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Often described as complex, opaque and unfair, the EU budget financing system is an "unfinished journey." One of the most critical issues is that EU revenue, drawn from the cashbox of national taxation, remains impalpable to the general public.

The nature of the EU as a union of states and their nationals makes the visibility of EU revenue unavoidable. The political sustainability of a move that would put the legitimacy of EU revenue at the forefront of public discussion will depend on the European Commission's ability to show that EU funds can achieve results that are truly beyond member states' reach.

The value-added tax (VAT) is a natural choice for funding the EU budget, through a dedicated EU VAT rate as part of the national VAT and designed as such in fiscal receipts, whose use as a means for raising EU citizens' awareness could be encouraged already in the current arrangements.

The nature of the EU as a union of states and their nationals makes the visibility of EU revenue unavoidable. The political sustainability of a move that would put the legitimacy of EU revenue at the forefront of public discussion will depend on the European Commission's ability to show that EU funds can achieve results that are truly beyond member states' reach.

The value-added tax (VAT) is a natural choice for funding the EU budget, through a dedicated EU VAT rate as part of the national VAT and designed as such in fiscal receipts, whose use as a means for raising EU citizens' awareness could be encouraged already in the current arrangements.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Financing the EU Budget by Gabriele Cipriani in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Public Finance. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

Public FinanceNot everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein

1. THE EU BUDGET REVENUE SYSTEM

The EU revenue system should be considered in the context of the highly innovative and evolutionary nature of the European Union, which is neither an international organisation nor a federal state. Originating from the decision by its member states to pool selected aspects of their respective sovereignties, the EU’s powers are founded on the principle of representation of interests.

The EU framework is based on a dual legitimacy, which “brings together states and peoples via a unique form of political integration”,1 in a process of governance ‘without government’ organised around a single institutional framework. The European Union constitutes a new legal order of international law, the subjects of which comprise not only member states but also their nationals.

The EU revenue system has been a subject of intense debate for years, in particular concerning the nature of the resources financing the EU budget. Many academicians have provided detailed reviews of the functioning and peculiarities of the system and have formulated a number of proposals to address its drawbacks. Still, the EU revenue system seems unalterable. In particular, no satisfactory solution has been found to make visible to citizens their contribution to the EU budget (some €140 billion in 2013, or an average of almost €280 per capita).

EU revenue: A short history

The evolution of the EU budget financing can be charted along the following timeline.

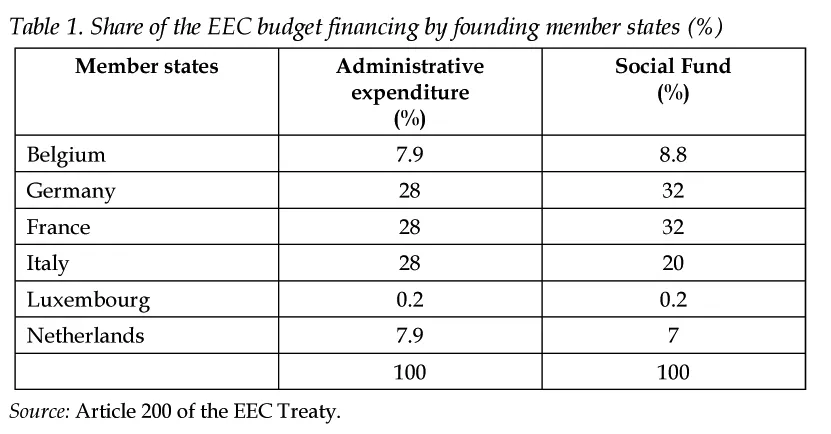

1952-1969. The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC, 1951, Treaty of Paris) was entitled to procure the funds necessary to carry out its tasks by setting levies on the production of coal and steel, which might be defined as the first Community tax (Article 49 ECSC). By contrast, the Treaty of Rome (EEC, 1957) provided that the budget of the European Economic Community would be initially financed from member states’ contributions (Article 200 EEC), as shown in Table 1, with the option of replacing them by Community’s own resources at a later stage (Article 201 EEC).

Member states’ contributions were based on a percentage scale provided for in the Treaty, differentiated according to the type of expenditure (administrative or operational). These scales were the result of a political agreement, although close to countries’ share in gross domestic product (GDP) at that time. The Council was entitled to modify the scales, by unanimous agreement. This happened notably in order to fund agricultural spending.

1970-1984. In 1970, after long and difficult negotiations, member states agreed that “the Communities shall be allocated resources of their own” and that “from 1 January 1975 the budget of the Communities shall, irrespective of other revenue, be financed entirely from the Communities’ own resources”.2 As a result, from 1971, customs duties, agricultural duties, and sugar and isoglucose levies (called ‘Traditional own resources’ or TOR) collected at EU entry were gradually transferred to the EU budget. In order to cover the administrative expenses for their collection, 10% of TOR was retained by the member states. Member states’ contributions from the value added tax (VAT)-based resource (1% of the taxable base) were made in full for the first time in 1980, covering around 50% of EU expenditure.

1985-1987. The call-up rate for the VAT-based resource was increased from 1% to 1.4% and the principle was formalised that any member state bearing an excessive budgetary burden in relation to its relative prosperity may benefit at the appropriate time from a correction. A correction was granted to the United Kingdom (the UK rebate), in the form of a reduction of its VAT-based resource payments, to be financed by the other member states (with Germany paying two-thirds of its share).

1988-1994. The principle of a multiannual financial framework (MFF) was introduced as a budgetary planning tool. Appropriations for payments were set by a global ceiling expressed as a percentage of member states’ total gross national product (GNP), increasing from 1.15% for 1988 to 1.20% for 1992. A new resource was levied at a uniform rate in proportion to the GNP of each member state, as a measure of a country’s prosperity.3 The GNP-based resource was also meant to function as a 'top-up' source of revenue to balance the budget, thus guaranteeing sufficient funding for the EU budget. In addition, while the maximum call-up rate for the VAT-based resource was maintained at 1.4%, member states’ VAT base was capped at a percentage (55%) of each national GNP. The reason invoked was to counter an alleged regressive effect of the VAT-based resource with relatively less well-off member states.4

1995-1999. The global own resources ceiling for payments was increased (from 1.21% for 1995 to 1.27% for 1999). There was also a progressive broadening of the capping of the VAT base (50% in 1999 for all member states) and a lowering of the call-up rate for the VAT-based resource (from 1.32% in 1995 to 1.0% in 1999).

2000-2006. GNP was replaced by the concept of gross national income (GNI).5 The global own resources ceiling for payments was slightly decreased (from 1.07% of GNI for 2000 to 1.06% for 2006). The maximum call-up rate for the VAT-based resource was reduced from 1% to 0.75% in 2002 and 2003 and to 0.50% from 2004 onwards. Starting with the calculation of the UK rebate in 2001, Austria, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden obtained to fund this rebate to a quarter of their normal share. As from 2001, the percentage of TOR that member states retain to cover collection costs was increased from 10% to 25%.

2007-2013. The global own resources ceiling for payments was set at 1.23% of GNI. The uniform rate of call of the VAT-based resource was reduced to 0.30%, although with some exceptions (for Austria it was fixed at 0.225%, for Germany at 0.15% and for the Netherlands and Sweden at 0.10%). A gross annual reduction in their GNI contribution was granted to the Netherlands (€605 million) and Sweden (€150 million).

2014-2020. While the global own resources ceiling for payments remains at 1.23% of GNI, the actual amount of payment appropriations has been lowered by almost 4% compared to the previous period. Reduced VAT-based resource rates (0.15% rather than 0.30% for the other member states) are applied to Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden. Moreover, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden will benefit from reductions of their national GNI payments of €130 million, €695 million and €185 million, respectively. The Austrian annual GNI contribution will be reduced by €30 million in 2014, €20 million in 2015 and €10 million in 2016. Finally, TOR collection costs retained by member states are reduced from 25% to 20%.6

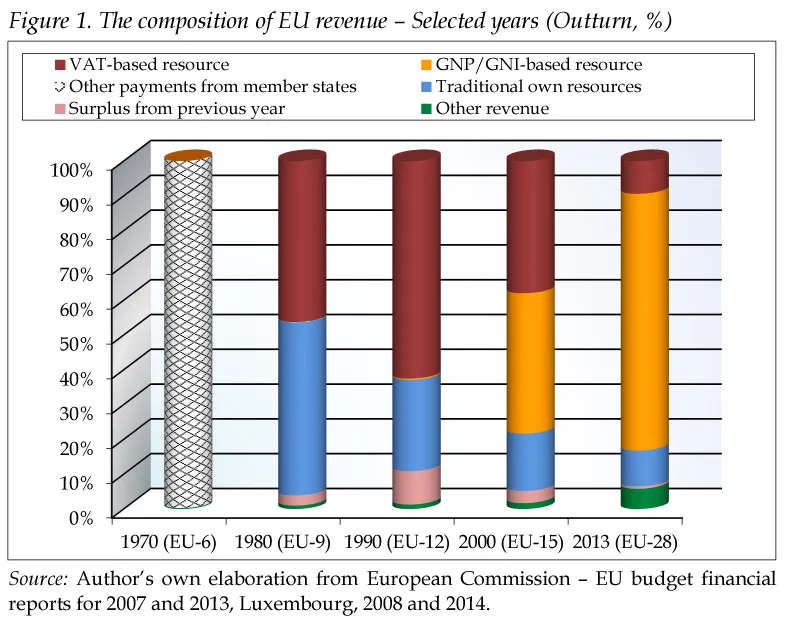

Figure 1 traces the evolution of the resources financing the EU budget since 1970.7

The figure shows that the pattern of revenue has undergone a profound modification over the years. This is principally due to the emergence of the GNP/GNI-based resource (74% of the own resources for the period 2007-2013) at the expense of the VAT-based resource, but also to the reduction of customs duties following the trade liberalisation and the increase of collection costs paid to member states as from 2001. Initially intended to complement the existing own resources, the GNP/GNI-based resource has become the dominant source of revenue as a conventional indicator of the contributive capacity of individual member states.

What do ‘own resources’ actually mean?

Following Article 3(6) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), “[t]he Union shall pursue its objectives by appropriate means commensurate with the competences which are conferred upon it in the Treaties”. Article 311 of the Treaty on the functioning of the European Union (TFEU) further clarifies that “[t]he Union shall provide itself with the means necessary to attain its objectives and carry through its policies. Without prejudice to other revenue, the budget shall be financed wholly from own resources”.8

It should be noted that the EEC founding Treaty provided for the Community budget to be financed in a first phase through member states’ contributions (Article 200 EEC), with possibly moving on to the Community’s ‘own resources’ at a later stage (Article 201 EEC). Thus, the Treaty of Rome set a clear distinction between these two types of funding sources. This transition, ensured in principle by the decision of 21 April 1970 “on the replacement of financial contributions from Member States by the Communities' own resources”, provided the political justification for giving the European Parliament budgetary powers.9

As observed by Ehlermann (1982:572, 584-585), the exceptional procedure required for adopting such a decision (unanimity in Council plus ratification by national parliaments) was similar to that for introducing direct elections of the European Parliament (Article 138(3) EEC). This coincidence should be interpreted as the wish to make the EU financially independent from member states, just as direct elections of the European Parliament severed its ‘umbilical cord’ with national parliaments. Therefore, the purpose of these provisions would have been to disengage the Community progressively from the member states.

The concept of ‘own resources’ was therefore meant to imply a shift of sovereignty on the part of member states, allowing the Community to exert a direct power of taxation over EU citizens. In this respect, Strasser (1991:91) defined ‘own resources’ as a tax borne directly by EU taxpayers which is included under revenue in the EU general budget and does not appear in the budgets of the member states.

Yet, the idea that the EU is financed by resources that belong to it by right as a cornerstone of its financial autonomy, and that therefore revenue accrues automatically without the need for any subsequent decision by national authorities, needs to be put into context and its evolution considered over time. In particular, a key overarching element of the EU financing system is that EU expenditure is subject to strict predictability (‘budgetary discipline’), ensured through three main features:

i.The overall volume of EU revenue is limited (since 1988) by an ‘own resources’ ceiling (for the MFF 2014-2020, payments shall not exceed 1.23% of the EU GNI). This ceiling is updated every year on the basis of the latest forecasts in order to guarantee that the EU's total estimated ...

Table of contents

- Preface

- 1. The EU budget revenue system

- 2. Simplicity, transparency, equity and democratic accountability

- 3. EU expenditure: The other side of the same coin

- References