eBook - ePub

Multilevel Governance and Climate Change

Insights From Transport Policy

- 306 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Multilevel Governance and Climate Change

Insights From Transport Policy

About this book

Based on a major three-year research project, this book explores the various roles of political actors and the policies that deal with the governance of reducing transport-related carbon emissions. Using this clear - and globally crucial - example of climate change governance, the authors are able to tease apart a range of debates and dilemmas and to fully explore the nature, pace and significance of core policies designed to tackle climate change.

Much research in the field has over-emphasized the international realm and global policy, whereas this text uncovers the huge importance that domestic policy development plays in reducing emissions. It highlights normative positions that lie at the heart of institutional structures, enabling broader debates into the capacity and future of democratic governance.

Much research in the field has over-emphasized the international realm and global policy, whereas this text uncovers the huge importance that domestic policy development plays in reducing emissions. It highlights normative positions that lie at the heart of institutional structures, enabling broader debates into the capacity and future of democratic governance.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Multilevel Governance and Climate Change by Ian Bache,Ian Bartle,Matthew Flinders,Greg Marsden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Environment & Energy Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

Environment & Energy PolicyI

Multi-Level Governance and Climate Change

1

The Climate Change Challenge

At one level the climate change challenge is very simple: Levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere have increased significantly since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, and this is causing Earth’s temperature to rise rapidly. The challenge is therefore to reduce CO2 emissions in order to stabilise or reverse this warming process. While simple in theory, the climate change challenge represents arguably the defining socio-political challenge of the twenty-first century. This is reflected in the unnerving titles of a number of leading texts on the topic, such as Elizabeth Kolbert’s Field Notes from a Catastrophe (2007), Alastair McIntosh’s Hell and High Water (2008) and Clive Hamilton’s Requiem for a Species (2010). The UK attracted worldwide interest and acclaim with the passing of ambitious and statutory targets for carbon reductions under the Climate Change Act 2008, but whether this political rhetoric and legislative activity has been matched by meaningful action on the ground is a question this book seeks to explore. Recent political history would suggest we should not be optimistic. As the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has illustrated in great detail, two decades of climate change mitigation policies have generally failed to curb global greenhouse gas emissions. And yet evidence of political failure makes the UK’s decision to adopt such ambitious and visible targets even more significant. Success could offer useful lessons for other countries to follow; failure and the climate change challenge becomes couched in ever more cataclysmic language.

One of the paradoxes of the climate change challenge, however, is that although there is a huge amount of technical and scientific data available (and an equally sizable body of research on the debate between the ‘believers’ and ‘deniers’), there is less scholarship on the governance of climate mitigation strategies. ‘Governance’ in this sense is used in the broadest terms to embrace not only institutional structures but also the social dimensions (in terms of lifestyles, customs, rituals, modes of living, etc.) and the political dimensions (in terms of the impact of the electoral cycle, the dysfunctions of democracy, etc.) and how these shape the capacity of local, regional, national and supra-national governments or associations to respond to the climate change challenge. It is for exactly this reason that this book focuses on the governance of carbon management in relation to transport policy and also why it highlights the political dimensions of reform processes, across varying levels, and how ‘the politics’ of climate change may sometimes hinder as much as help the design and implementation of carbon reduction strategies. What this focus on institutions, society and politics provides is an understanding of the climate change challenge as a ‘super wicked’ problem (Lazarus 2009), and the aim of this chapter is to sketch out the contours of this challenge from a number of perspectives. More precisely, this chapter presents the climate change challenge as very much an issue of multi-level governance that transcends institutional, political and territorial boundaries and, as such, raises fundamental questions about the capacity and resilience of democratic politics.

In order to present this multi-dimensional account of the climate change challenge, this chapter is divided into five sections. The first section focuses on the current science base and provides an overview of the findings of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC 2013) in relation to both the scale of the climate change challenge and the success of various mitigation strategies. With the available science base set out, the central aim of this chapter is to tease apart exactly what makes the climate change challenge apparently so intractable. What is it that seems to make the climate change challenge such a difficult issue for politicians and policymakers to deal with? In order to answer this question, we offer three core (and inter-related) explanations that focus on institutions, society and democratic politics. The second section therefore focuses on the institutional governance of climate change and highlights the manner in which a complex institutional architecture creates a gap between the scale of the challenge and the capacity for a coordinated response.

But to define the climate change challenge simply as one of institutional failure would be to over-simplify the issue. Indeed, climate change is a ‘super-wicked’ problem due to a number of far deeper and socially embedded dimensions of modern governance that need to be acknowledged if the challenge is to be addressed. The third section therefore shifts the lens of analysis from the institutional sphere to the social sphere and focuses on social consumption, everyday lifestyle practices and transition theory. What this third section therefore offers is a critique of the dominant ‘ABC approach’ (Shove 2010) with its emphasis on an individualised and choice-based policy response to the climate change challenge and a richer account of why change away from high-energy, carbon-intense patterns of behaviour appears so difficult. This focus on ‘institutional governance’ and what might be termed ‘social governance’ flows into the fourth section’s focus on ‘democratic governance’ and a discussion about the politics of climate change. What this focus on short-termism, perverse incentives and the pathologies of maintaining popular support provides is a deeper account of exactly why the climate change challenge is so ‘wicked.’ The institutional, social and political components of the challenge are arguably inter-woven and inter-dependent to such an extent that inertia and ‘business as usual’ can too easily emerge as the default position (alongside minor elements of ‘greenwashing’). This has, as we will discuss, led to far-reaching debates about the climate change challenge and the failure of democracy. The final section of this chapter attempts to weave and pull these three strands together—the institutional strand, the social strand and the political strand—in order to reflect upon three themes: What do we know? Why does it matter? Where are the gaps in our knowledge?

1.1 Science

The climate change challenge, and notably the politics of climate change, has for some time been dominated by a rather unhelpful binary divide between those who believe that the climate is subject to a natural variability that can be seen from long-term records and those who believe that anthropogenic climate change is significantly impacting over and above the natural cycles. These ‘climate wars’ (Mann 2013) have tended to produce far more heat than light in terms of developing our understanding of the climate change challenge and how it might be addressed.

Notwithstanding the evidence of natural climate variability, a key finding from the IPCC’s working groups in March 2014 was that ‘it is extremely likely that human influence has been the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century’ (emphasis in the original). The science therefore accepts (as reflected in figure 1.1) that climate change is driven by a combination of natural factors and anthropogenic factors, but even allowing for the findings of paleoclimate reconstructions that extend some records back millions of years, the science regarding man-made climate change is largely unambiguous. As the IPCC stated in their Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Base (4):

Warming of the climate system is unequivocal, and since the 1950s, many of the observed changes are unprecedented over decades to millennia. The atmosphere and ocean have warmed, the amounts of snow and ice have diminished, sea level has risen, and the concentrations of greenhouse gases have increased.

Figure 1.1. Climate Change: Hazards, Vulnerability and Exposure

Source: IPCC 2014a, 3.

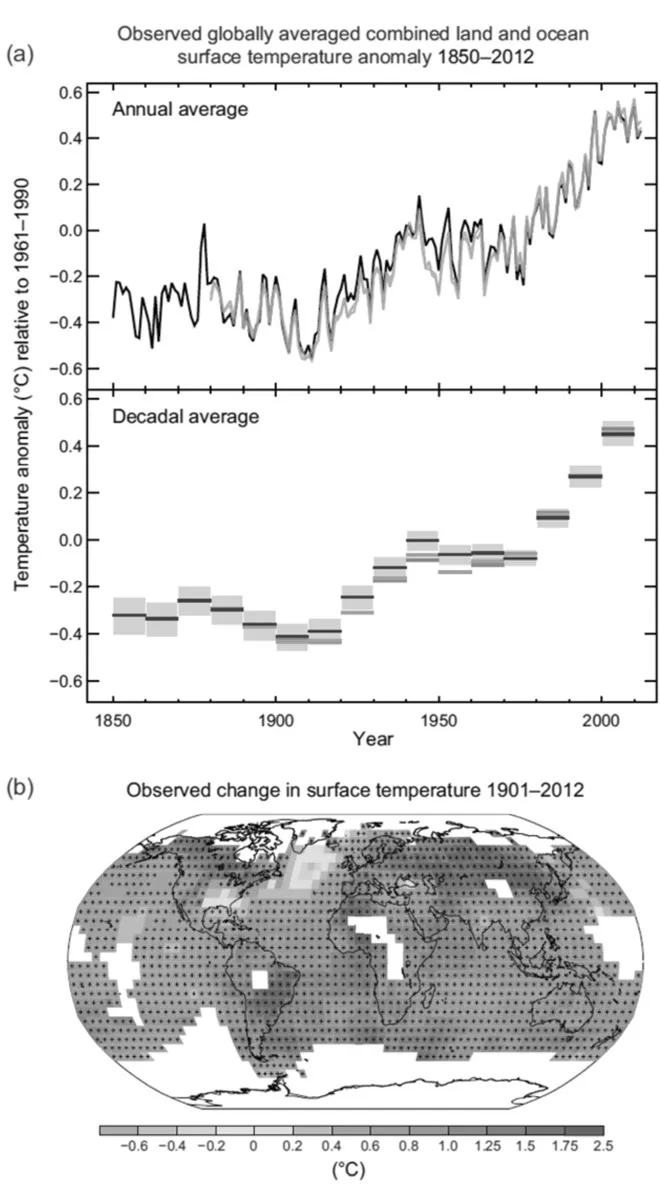

The science is therefore clear when it comes to climactic change. Each of the last three decades has been successively warmer at Earth’s surface than any other preceding decade since 1850. In the Northern Hemisphere the period 1983 to 2012 was likely the warmest thirty-year period of the last 1,400 years (see figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Observed Globally Averaged Combined Land and Ocean Surface Temperature Anomaly, 1850–2012

Source: IPCC 2013, 3.

Ocean warming dominates the increase in energy stored in the climate system, accounting for more than 90 percent of the energy accumulated between 1971 and 2010, and the upper ocean is warming fastest and sea levels are rising. In September 2012, Arctic sea ice hit its lowest level ever recorded, at 3.41 million square kilometres. Not only had the coverage of the sea ice shrunk to barely half the 1979 to 2000 average size, its volume had declined by 72 percent (that is, ice cover had shrunk while also becoming much thinner). Peter Wadhams, director of the Polar Ocean Physics Group, described these findings as a ‘global disaster’ and suggested that the Arctic sea ice will probably have disappeared by 2016.

The principal causes of these changes have been the unprecedented increases in the atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide, which are now at levels not seen in at least the last eight hundred thousand years (as revealed through the analysis of ice cores). These so-called greenhouse gases (GHG) keep more of the energy from the sun trapped within the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide concentrations have increased by 40 percent since preindustrial times, primarily due to fossil fuel emissions, cement production and changes in land use. From a largely stable preindustrial average of around 280 parts per million (ppm), this figure had risen to 397 ppm in November 2014 and appears to be increasing at a rate of around 20 ppm per decade—a level far beyond nature’s built-in compen...

Table of contents

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I: Multi-Level Governance and Climate Change

- Chapter 1: The Climate Change Challenge

- Chapter 2: Theorizing Meta-Policy Implementation in Multi-Level Polities

- Part II: The Politics of Carbon Management and Transport Governance

- Chapter 3: Why Transport Matters

- Chapter 4: Climate Change and Transport Governance

- Chapter 5: England: Greater Manchester and West Yorkshire

- Chapter 6: Scotland: Strathclyde and South East Scotland

- Part III: Analysis and Implications

- Chapter 7: The Politics of Implementing Climate Change Targets: A Symbolic Meta-Policy?

- Chapter 8: Where and How Does Accountability Exist?

- Conclusion

- References