- 202 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The book explores in depth both the origins of the Greek debt crisis and the conditions under which the economy might be turned around from its current malaise. Greek debt turned explosive after the 2008 global crisis, through a combination of a fiscal spree and domestic policy complacency, but the unpreparedness and indecision of the European Union intensified the problem of liquidity and a massive bail-out agreement became inevitable.

However, the stringencies of the adjustment program led to more recession and unemployment, while social tension and political polarization became entrenched. In 2015, a radical Left party, Syriza, ascended to power on a ticket to end austerity and renegotiate Greece's debt agreements, but a long-lasting growth and reform agenda is still to be settled upon. This book lays out some key reforms that would allow Greece to return to growth and, at the same time, keep the Euro, an option that still remains a cornerstone for the country's economic and geopolitical stability.

,

However, the stringencies of the adjustment program led to more recession and unemployment, while social tension and political polarization became entrenched. In 2015, a radical Left party, Syriza, ascended to power on a ticket to end austerity and renegotiate Greece's debt agreements, but a long-lasting growth and reform agenda is still to be settled upon. This book lays out some key reforms that would allow Greece to return to growth and, at the same time, keep the Euro, an option that still remains a cornerstone for the country's economic and geopolitical stability.

,

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Greek Endgame by Nicos Christodoulakis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & International Business. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

THE RUN-UP TO THE CRISIS

Chapter 1

Origins

How Greece Was Engulfed in the Crisis

The origins of the current malaise can be traced back to the overgrown public debt in the 1980s. Though fiscal imbalances were partially corrected and Greece joined the single currency in 2000, further reforms were delayed after accession to the EMU and deficits gradually slipped beyond the limits of the Stability and Growth Pact. The image of Greece in world markets was further tarnished by the fiscal audit that took place in 2005 and by the Goldman Sachs swap executed in 2001 to reduce exposure to the Japanese yen. The increasing incapacitation of the revenue-collection mechanism and a parallel expansion of public spending prevented the government from effectively responding to the 2008 global crisis, only to be followed by further expansionary policies by its successor.

1.1. The Debt-Escalating Period: 1980–1993

In 1981, Greece became a full-fledged member of the European Economic Community (EEC) and this marked a whole new period for the economic and political development of the country. Greece was one of the first non-founding countries to start accession talks with the European Common Market as early as 1961, but the process was abruptly suspended by the military dictatorship that lasted until 1974. Though membership of the EEC was rightly viewed as an anchor for political and institutional stability for the newly restored democracy, it nonetheless fed and multiplied uncertainties over the ability of the Greek economy to survive in international markets.

It didn’t take long for such fears to be substantiated. After a long period of growth, Greece entered a period of recession in the late 1970s, not only as a consequence of worldwide stagflation but also because—on its way to integration with the common market—it had to dismantle its preferential system of subsidies, tariffs and state procurement by which several companies were kept profitable without being competitive. Soon after accession, many of them went bust and unemployment rose for the first time in many decades.

To accommodate some of the recessionary effects, fiscal policy turned expansionary. As a result, accession to the EEC strangely coincided with the unleashing of a demon that was thought to have been dormant thus far: public debt.

1.1.1. Accumulating Debt

In the early 1980s the government opted for a massive fiscal expansion that included demand-push policies to boost activity and the public underwriting of ailing private companies to maintain employment. The effect was quite predictable: private debt turned to a chronic hemorrhage of budget deficits without any supply-side improvements. Similarly, the expansion of demand simply led to more imports and higher prices. Activity got stuck and Greece ended up in a typical stagflation, perhaps the quickest assimilation to the European practices of the time.

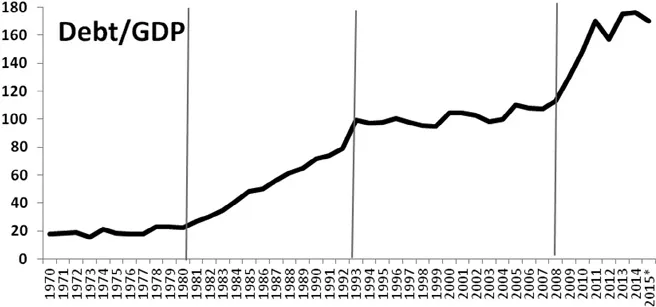

Looking at Figure 1.1, there are three distinguishable phases for the dynamics of debt: The first covers the period 1980–1993 during which public debt rose from slightly above 20% of GDP towards 100% in 1993. The second phase spans the period 1994–2005 in which public debt ends up again at around 100% of GDP after two mild reductions in between. The third phase covers the period 2006–2011 during which public debt surpasses the 100% threshold, accelerates after 2008 and ends up at 129% of GDP in 2009, triggering the crisis.

Figure 1.1 Greek Public Debt as Percent of GDP. Source: AMECO Eurostat. General government. Excessive deficit procedure, based on ESA 2010 and previous definitions. (Variable UDGG). For 2015, estimates.

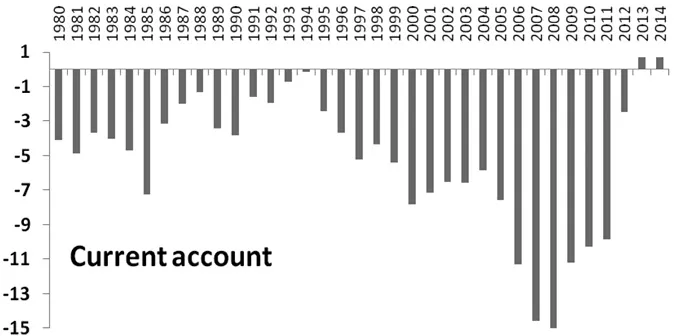

Figure 1.2 Current Account as Percent of GDP. Source: IMF WEO Database 2014.

The above periodicity broadly coincides with substantial shifts in the context of economic policies, as suggested by developments in the fiscal patterns and the current account shown in Figure 1.2. Fiscal developments are in more detail displayed in Figure 1.3 and briefly discussed below.

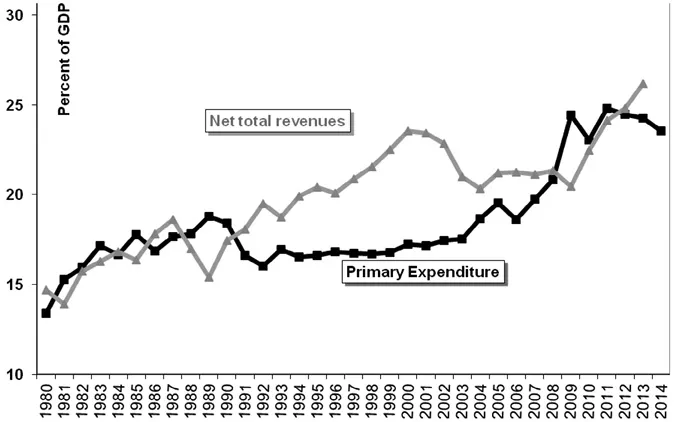

The main characteristic of the first phase was the substantial expansion of public spending and the concomitant rise in budget deficits and government debt. Revenues increased as a proportion of GDP, but were outpaced by the steadily growing expenditure. Both fiscal components appear to be volatile in election years (e.g. in 1981, 1985, 1989 and 1993), suggesting that a strong political cycle was put in motion with adverse consequences on stabilization efforts.

Since the collapse of Bretton Woods in 1972, the authorities had adopted the so-called system of a ‘crawling peg’ in which gradual nominal depreciation is used to offset inflation differentials with competitors and, thus, maintain a real exchange-rate target. After the government introduced an automatic wage indexation scheme in 1982, in order to immunize wages from the effects of inflation, a vicious circle was set off: the only effect of the exchange rate policy was to augment price, thus leading to wage increases that fuelled inflation and aggravated trade deficits all over again. To break the loop of depreciation and inflation, a discrete devaluation combined with a temporary wage freeze was implemented in 1983. Soon, however, the restrain effect was superseded by a new phase of expansion and pay rises as elections were approaching. Public debt simply climbed to higher levels.

The external deficit approached 8% of GDP in 1985: this was an alarming threshold as several Latin American economies with similar imbalances were serially collapsing at that time. A coherent stabilization programme was called for in October 1985 enforcing a discrete devaluation by 15%, a tough incomes policy and extensive cuts in public spending. The programme achieved a rise in revenues by cracking down on several tax-evasion practices and replacing previous indirect taxes with the more effective VAT system adopted by the EEC. Public debt was stabilized, but only until the programme was finally abandoned in 1988, after being fiercely opposed from within the government and the ruling party.

Figure 1.3 Primary Public Expenditure and Net Total Revenues as Percent of GDP. Note: Revenues for 2014 not yet finalized. Source: Ministry of Finance, Greece. Budget Reports, various years.

1.1.2. The First Fiscal Crisis

Two general elections in 1989 failed to secure a majority government, thus leading to the formation of coalition governments, an event that was hailed as a confirmation of political maturity and an opportunity to overcome partisan differences on major issues. But these self-indulgent expectations were short-lived, as stabilization policies are notoriously difficult to be implemented through party coalitions because each party tries to avoid the cost falling on its own constituency. Greece was no exception to this rule, and the economy suffered a major setback in 1989–1990 that was far more serious than previous fiscal failures.

Two episodes are characteristic of how rhetoric designed to please everybody in combination with naïve policies can lead to disaster: despite looming deficits in 1989, the coalition government decided to abolish prison terms for major tax arrears, hoping to induce offenders to reconsider their strategy. As might be expected, the move had the opposite effect and was rather taken as a signal of relaxed monitoring in the future, thus encouraging further evasion.

Another bizarre policy was to cut import duties for car purchases by impoverished repatriates returning to Greece after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The measure was viewed as a gesture to facilitate mobility back in the motherland, but it was quickly turned into a black-market scam. For a small bribe, immigrants would purchase luxury cars only to resell them immediately to rich clients, who thus avoided paying any duties for importing them into the country.

With revenues collapsing, the country began to suffer a major strain in public finances until a majority government was elected in 1990 and enacted a new stabilization programme. Despite substantial cuts in spending and a rise in revenues, public debt as a ratio to GDP continued to rise, this time due to the higher cost of borrowing worldwide and a stagnant output. The sharp rise in 1993, in particular, was due to the inclusion of extensive debts initially contracted by public companies under state guarantees but finally underwritten by the Treasury. The subsequent fiscal consolidation significantly improved the current account and the rarity of a balanced external position was briefly achieved in 1994.

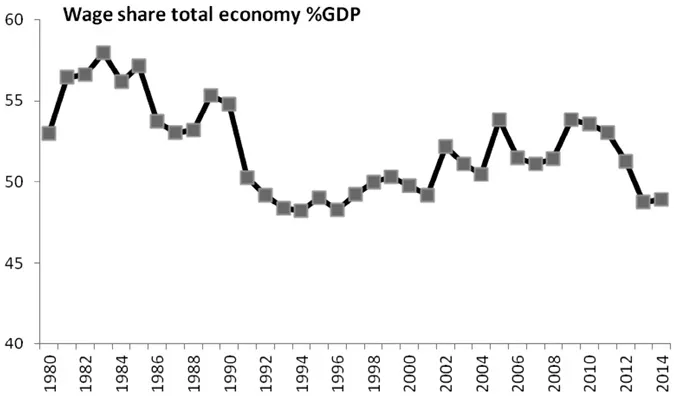

In the 1980s, extensive wage increases took place both in the public sector, where the government capitulated to aggressive trade union demands, and in the private sector by raising minimum wage levels and establishing collective bargaining agreements. As shown in Figure 1.4, the wage share reached nearly 60% of GDP in the early 1980s but then declined as a result of the stabilization programme in 1985–1987. After a blip in the period of fiscal instability in 1989, it kept on falling to around 50% in the early 1990s.

Figure 1.4 The Wage Share in Total Economy. Source: Ameco Eurostat.

1.2. Debt Stabilization and EMU Membership

Although Greece was a signatory of the Maastricht Treaty in 1991, it was far from obvious whether, how and when the country would comply with the nominal convergence criteria required to join the Economic and Monetary Union. Public deficits and inflation were galloping at two-digit levels and there was great uncertainty about the viability of the exchange rate system.1 In May 1994, capital controls were lifted in compliance with European guidelines and this prompted a fierce speculation in the forex market. Interest rates reached particularly high levels and the Central Bank of Greece exhausted most of its reserves to stave off the attack. This episode proved to be a turning point for the country’s determination to pursue accession to EMU in order to be shielded by the common currency and to avoid similar attacks in the future. Soon afterwards the ‘Convergence Programme’ was adopted with a specific timeframe to satisfy the Maastricht criteria. A battery of reforms in the banking and the public sectors was also included.

Nevertheless, international markets were not impressed and remained unconvinced about exchange rate viability. At the eruption of the Asian crisis in 1997, spreads rose dramatically and—after months of credit shortages—Greece finally decided to devalue the drachma by 12.5% in March 1998 and subsequently enter the Exchange Rate Mechanism wherein it had to stay for two years. Greece obviously was not yet ready to join the first round of Eurozone countries in 1998, thus a transition period was granted allowing her to comply with the convergence criteria by the end of 1999.

After depreciation, credibility was further enhanced by structural reforms and reduced state borrowing so that when the Russian crisis erupted in August 1998, the currency came under very little pressure. Public expenditure was kept below the peaks it had reached in the previous decade and was increasingly outpaced by rising revenues and various one-off receipts. Tax collection was enhanced by the introduction of a framework setting a minimum turnover on SMEs, the elimination of a vast ...

Table of contents

- Cover-Page

- Half-Title

- Introduction

- PART I: THE RUN-UP TO THE CRISIS

- PART II: THE BAILOUT YEARS

- PART III: THE ILLUSIONS

- PART IV: THE ESCAPE

- Epilogue: After the Left’s Victory in Greece

- Postscript

- Relevant Books and Research by the Author

- References

- Index