- 70 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

After its disastrous defeat in 2015, Labour is at grave risk of throwing away the 2020 general election. The party has to understand why it suffered such a devastating defeat and learn crucial lessons if it is to recover. The reasons appear obvious enough: the British public did not believe that Ed Miliband was a credible prime minister; people feared that a Labour government would plunge the British economy back into chaos; and they perceived that the party was out of touch on issues like immigration and welfare. Labour was not just narrowly defeated in 2015, it was overwhelmingly rejected by an electorate who no longer trust the party.

Underlying all of this is a sense that Labour is a party that does not understand the modern world, wedded to an outdated 'cloth cap' image of heavy industry and the monolithic public sector. The risk for the Labour party, like social democratic parties across Europe, is further electoral defeat and then inevitably, permanent irrelevance. As of today, there are few signs that the party grasps why it lost and, in particular, why swing voters in marginal seats were not prepared to vote Labour. A party that does not understand why it was defeated scarcely deserves to be taken seriously by the electorate. This book examines why Labour so overwhelmingly lost the trust of voters, and crucially how the party under a new leader can win them back by 2020 – charting Labour's path to power.

Underlying all of this is a sense that Labour is a party that does not understand the modern world, wedded to an outdated 'cloth cap' image of heavy industry and the monolithic public sector. The risk for the Labour party, like social democratic parties across Europe, is further electoral defeat and then inevitably, permanent irrelevance. As of today, there are few signs that the party grasps why it lost and, in particular, why swing voters in marginal seats were not prepared to vote Labour. A party that does not understand why it was defeated scarcely deserves to be taken seriously by the electorate. This book examines why Labour so overwhelmingly lost the trust of voters, and crucially how the party under a new leader can win them back by 2020 – charting Labour's path to power.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Can Labour Win? by Patrick Diamond,Giles Radice,Penny Bochum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & European Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

European PoliticsThe Electoral Battleground

Polling Analysis and the Views of Wavering Voters

This chapter presents the quantitative polling research carried out by Ipsos Mori alongside the key findings of our qualitative survey carried out among voters across England, Wales and Scotland.1 The poll was conducted 10 days before the general election; it provides a snapshot of the electorate’s attitudes and views as they weighed up which way to vote in the period up to 7 May.2 The chapter focuses on voters’ perceptions of Labour and examines why so many were not prepared to support the party at the 2015 election.

The results underline the scale of the political challenge now facing Labour in the wake of its election defeat. In 2010, our research for Southern Discomfort Again found deep disillusionment after 13 years of Labour government and the financial crisis. Since then, the party appears to have gone backwards: its strategic position is, in key respects, worse than it was five years ago. We found evidence of important differences of social class and geography in voters’ attitudes, which partly explains Labour’s variable regional performance and its inability to connect with large swathes of England. These voters recognise that Labour has a social conscience and wants to make Britain fairer, but they have little confidence in the party’s economic management credentials seven years on from the financial crash. They will not take much notice of Labour’s social vision until they can be sure the party will not plunge Britain back into economic chaos.

Britain today is an economically anxious country where faith in politics has fallen to an all-time low. Middle-income, working- and middle-class Britain feels increasingly betrayed, unable to have confidence in any of the established political parties. These voters are aspirant and as anxious to get on in life as ever, but they are cautious about their prospects in the face of rising job insecurity, declining real wages, plummeting living standards and, as a consequence, a major increase in household debt. They want a better future for their children and grandchildren, but worry that life is set to get even tougher and that the advantages of a middle-class lifestyle – a steady, well-paid job, owning your own home, regular foreign holidays, a decent education – will be even harder to attain for the next generation. Middle-income Britain wants hope in the face of pessimism and uncertainty.

Labour Has Gone Backwards Since 2010

Labour today is seen as less of a national party than it was in 2010:

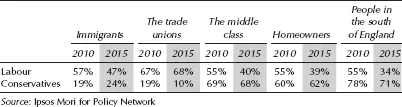

- Only one-third of voters (34 per cent) now say that Labour is close to people in the south of England, compared to 55 per cent in 2011 (see Table 2.1). Unsurprisingly, 71 per cent say the Conservatives are close to people in the south.

- This is mirrored by a fall in the proportion of voters who say that Labour is close to the middle class, down from 55 per cent in 2010 to 40 per cent today. This compares to 68 per cent for the Conservatives.

- In 2010, Labour and the Conservatives were seen as relatively equal in terms of being close to those who own their own home (55 and 60 per cent respectively). By 2015, the proportion of voters who saw Labour as close to home-owners fell to 39 per cent, while it remained at a similar level (62 per cent) for the Conservatives.

- Labour’s pursuit of the ‘35 per cent strategy’ targeting ‘core’ Labour voters and disaffected left-leaning Liberal Democrats appears to have markedly narrowed its base of support. The party is now perceived as close to the working class by a margin of 62 to 24 per cent.

Table 2.1 Who are Labour and the Tories close to?

Despite reforming its links with the trade unions, a similar proportion of voters (68 per cent) perceive Labour to be close to the unions as in 2010 (67 per cent). One area in which Labour has apparently made some progress is in pursuing a tougher stance on immigration. Less than half of voters (47 per cent) now believe that Labour is close to immigrants, compared to 57 per cent in 2010 – then hardly surprising perhaps in the wake of Gordon Brown’s travails with Gillian Duffy in Rochdale. The Conservatives are now seen as somewhat closer to immigrants (24 per cent compared to 19 per cent), which is no doubt reflected in rising support for Ukip. When asked whether Labour was more interested in helping immigrants instead of those born in Britain, voters were evenly divided (33 per cent agreed; 33 per cent disagreed). We return to this theme below.

Labour’s electoral strength is that many voters would like to trust and support the party: they identify with Labour’s broader mission of a fairer society with opportunities widely spread. As one voter said: “I would like to vote Labour next time. They represent my sort of experience more than the Conservatives.” Another added: “For me, it’s always a struggle not to vote for Labour. I would naturally vote Labour, I voted for Blair and Brown.” When Labour had been on the brink of government before, one younger voter felt a sense of optimism about the future: “A couple of times in my life I felt there was some kind of hope, like when you had [Bill] Clinton and Blair. I felt change was possible . . . I am from a strong Labour family. Labour was part of my life. I was so excited when Tony Blair got into power. I genuinely believed it marked a new era of politics.”

The Party of Economic Incompetence

Labour has made little progress since 2010 in addressing its key strategic weakness: a reputation for economic incompetence. Only 16 per cent of voters trust the party most to run the economy – exactly the same figure as in 2010 – compared to 33 per cent for the Tories (in the south-east, the margin is 42 to 11 per cent). In the south of England (outside London), the figure falls to 11 per cent.3 Just 12 per cent of voters trust Labour most to reduce the budget deficit, the same figure as in 2010 (falling to eight per cent in the south). In the West Midlands, the Conservatives are more trusted than Labour to reduce the deficit by 44 to 10 per cent. The Labour leadership’s argument that the deficit was rising under the Conservative chancellor, George Osborne, because of falling real wages (and therefore of declining tax revenues) completely failed to connect with voters.

Since the financial crash, Labour has utterly failed to restore its economic credibility with the electorate. When asked to choose which term best described today’s Labour party, 44 per cent of voters in the south selected “incompetent”: across Britain, the figure was 37 per cent. The voters we interviewed had little sense of what Labour’s economic policy actually amounted to. What they did remember was scarcely advantageous to the party’s reputation: “There was a sense they were against people who generate wealth.”

Labour was still blamed for the crash and the deficit by most of the respondents, and not felt to have policies to deal with the deficit: “They messed things up in 2010. They screwed up on the economy. Even if they didn’t overspend, they didn’t put the case well that they didn’t overspend.” Another voter was adamant: “The Labour attitude to spending was wrong and they were reluctant to admit the Labour government spent too much. They overspent, they were blind about the financial troubles and they don’t admit that.” Voters wanted Labour to recognise that the deficit was a problem and had to be addressed head on by whoever was in government: “They are anti-austerity and want to continue spending and I agree with the Conservative policy of paying off the debt. That is essential and I disagree with Labour. You’ve got to try and pay it back; you’ve got to take that seriously. I mean, look at the mess they made. And they left the Conservatives to deal with it and we are all still paying for that.”

Nonetheless, the Conservatives were scarcely applauded for their economic performance: trust in them to run the economy fell from 44 per cent to 33 per cent between 2010 and 2015 reflecting the anaemic recovery and the stagnation of wages and living standards. Osborne missed his government’s deficit reduction targets: as a result, trust in the Conservatives to reduce the budget deficit fell from 51 per cent in 2010 to 35 per cent by 2015. That said the Conservatives were notably more trusted on the deficit in southern England (40 per cent).

The mood in Britain remains markedly pessimistic seven years after the financial crisis first struck. When asked “whether children growing up in Britain today are likely to face a tougher time as adults than their parents’ generation”, 68 per cent agreed against seven per cent who disagreed. A majority were not confident their children or grandchildren would be as secure financially (51 to 40 per cent), able to fulfil their educational potential without incurring large debts (64 to 28 per cent), or to buy a home before they are thirty (69 to 23 per cent). The electorate’s attitude today is stoic but hardly upbeat: 32 per cent expect life to be tough but they will get by; 30 per cent think they’ll be “just about ok”. Those currently in work were less confident they would find a...

Table of contents

- Cover-Page

- Half-Title

- Introduction: Why Did Labour Lose?

- The Electoral Battleground: Polling Analysis and the Views of Wavering Voters

- Why Labour Lost: Party Views

- What Labour Must Do

- Conclusion: Labour’s Hard Road to Power