- 244 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Protest Campaigns, Media and Political Opportunities

About this book

The attention paid to protest groups and social movements has rarely been higher, be it the Occupy movement, austerity protests, or student demonstrations. These formations are under continual scrutiny by academics, the press and politicians who are all attempting to interpret and understand protest groups, their tactics, demands, and their wider influence on society.

Protest Campaigns, Media and Political Opportunities takes an in-depth look at three different protest groups including a community campaign, environmental direct action activists, and a mass demonstration. It offers a broad perspective of each group through a comprehensive combination of insider stories from activists, the authors own involvement with one group, newspaper coverage, each group's social media, websites and leaflets, and government documents. This wealth of material is pieced together to provide compelling narratives for each group's campaign, from the inception of their protest messages and actions, through media coverage, and into political discourse.

This book provides a vibrant contribution to debates around the communication and protest tactics employed by protest groups and the significance news media has on advancing their campaigns.

Protest Campaigns, Media and Political Opportunities takes an in-depth look at three different protest groups including a community campaign, environmental direct action activists, and a mass demonstration. It offers a broad perspective of each group through a comprehensive combination of insider stories from activists, the authors own involvement with one group, newspaper coverage, each group's social media, websites and leaflets, and government documents. This wealth of material is pieced together to provide compelling narratives for each group's campaign, from the inception of their protest messages and actions, through media coverage, and into political discourse.

This book provides a vibrant contribution to debates around the communication and protest tactics employed by protest groups and the significance news media has on advancing their campaigns.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Protest Campaigns, Media and Political Opportunities by Jonathan Cable in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

Protest Groups and Contentious Politics

Now more than ever, there is a great focus on social movements and protest groups all around the world such as Occupy in New York or the Arab Spring across the Middle East and North Africa. Just in the United Kingdom since the Labour government were ousted from office in 2010, we have seen a wide spectrum of people taking action and different issues protested: against austerity, tax evasion and avoidance by UK Uncut, protests by trade unions, local anti-fracking protests, student fees protests, junior doctors on strike, demonstrations against the government sell-off of the United Kingdom’s forests, continued direct action against aviation expansion, and hacktivist collective Anonymous’ actions against scientology. With this in mind, this book makes a number of significant contributions to social movement studies. It focuses on a range of different areas of research from the somewhat neglected area of community campaigning to the much more academically visible environmental protests and mass demonstrations. Each group can be considered as local, national, or transnational and thereby provides broad perspectives of approach to politically contentious issues. It examines how the campaign objectives and decision-making processes behind a group’s media and protest tactics, and how these choices impact on media and political opportunities. This book draws upon many different areas such as from social movement studies and political science to media studies and political communication. In doing so, the old assumptions that positive media and political acceptance are a sign of success are addressed and looked at more from the protester perspective and their own particular aims and goals.

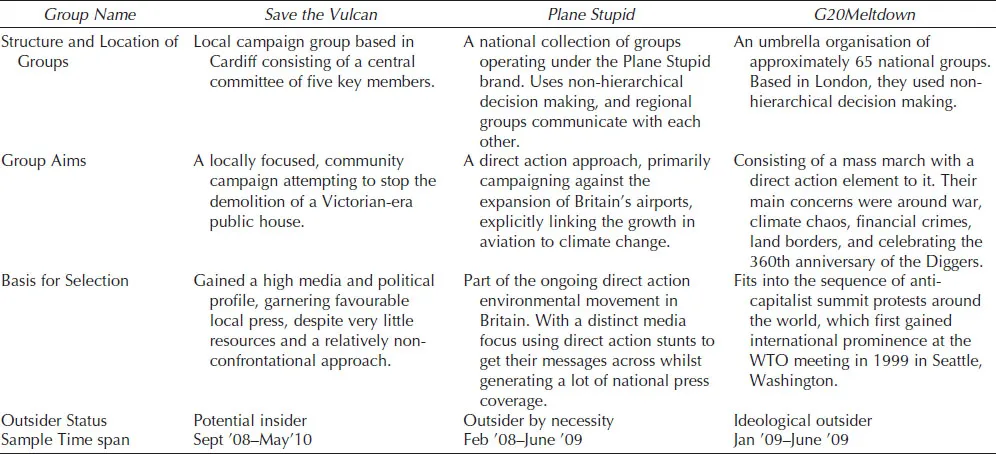

To gain a broader understanding of the factors influencing protest groups, three different case studies have been presented. The groups chosen protested on different issues, used a variety of protest and media tactics, and reside within different media and political contexts. The groups selected included the Save the Vulcan campaign, Plane Stupid, and G20Meltdown. The ‘Save the Vulcan’ campaign was a community-based group protesting over the proposed demolition of a Victorian-era pub. ‘Plane Stupid’ is an environmental direct action group protesting against the expansion of the aviation industry and the United Kingdom’s airports, and linked the growth of airports to climate change. They used non-violent symbolic direct action to attract media coverage and publicise their messages, and aimed to prompt debate around airport expansion, but they were not concerned with political and media acceptance. The third and final group was ‘G20Meltdown’, who held a mass demonstration against the Group of 20 summit (G20) in London on the 1 April 2009. G20Meltdown was an umbrella network of up to 60 groups, and primarily protested about climate change, war, land borders/homelessness, and financial crimes. They were less orientated towards actively courting the media compared to the other two groups, and only used one protest event to highlight their messages. More about these groups, why they were chosen, and what they did will be discussed later in this chapter and throughout the book. The different modes of communication employed by each group, and the reactions of the press and dominant institutions mean that this book offers a deeper understanding of the processes that shape collective action.

Key Themes

This book is fundamentally orientated around several key scholarly debates relating to (1) political opportunities, resource mobilisation, and the signalling model and their effect on a protest group’s goals, and media and protest tactics; (2) the claims-making role of protest groups when attempting to gain media access, and (3) the political contest model – collective action framing and media framing. These debates provide the conceptual framework used throughout the book and are formulated around the creation, identification, and exploitation of political opportunities by protest groups. It follows that political opportunity structures provide a backdrop to a group’s media and protest tactics. However, these cannot be considered in isolation. The protest group’s frames and messages, and the importance of the media in publicising these messages are emphasised. The main point is that media and political opportunities shape the success and failure of a protest group to reach their goals.

Protest groups in contemporary society are involved in highlighting and championing causes that are politically contentious. These contentious issues take many different forms ranging from identity politics, to cultural, social, economic, or political issues. Essentially, these issues encapsulate everything from gay rights to ‘not in my backyard’ campaigns. Klandermans talks about grievances as originating from the “structural conflict of interests” that exist throughout society (1986, 19). This conflict is where political contention exists and is exacerbated by the interactions between protest groups, their protest targets, and the mainstream media. These interactions are influenced by a variety of different environmental variables, and it is these variables that guide the success and failure of protest groups to achieve their goals. It is this dimension of political contention where it helps to know what the aims and goals of a protest group are, and how these fundamentally influence their media and protest tactics.

To theoretically contextualise the influences on collective action is to consider political opportunities. The definition of political opportunities ties the relative success and failure of protest groups to political, institutional, and environmental variables that shape collective action (Eisinger 1973; Gamson and Meyer 1996; Meyer 1993; Meyer and Minkoff 2004; Sireau 2009). The theory of political opportunities is very structural, and forms the basis of the first of three arguments at the centre of the book. The first key argument is that the role of the media in political opportunities has not been granted sufficient enough theoretical prominence, because today, invariably, the media is the focal point and site of political debate. It is essentially a debate around the distribution of power and is described by Wolfsfeld as

The relative power of either side – a given news medium and a given antagonist – is determined by the value of its services divided by its need for those offered by the other. (2003, 84)

Power in this case refers to “relative dependence” (ibid, 84), or who needs who more. This power equation is weighted towards the media. Put simply, they are not obliged to cover a protest group. It follows that media power and their involvement in contentious politics is due to their ability to signal to dominant institutions which issues are important and should be addressed. Therefore, this addition needs to be considered in order for political opportunities to be more flexible and applicable when analysing all different types of protest groups, and not just those who want positive media coverage and political acceptance. There have been attempts at refining the concept already. First, Meyer and Minkoff quite rightly talk of issue-by-issue opportunities where the potential for success is not just viewed from a static, slow moving, and political institutionally dependent model. Instead, they looked more at the respective influences when a protest group emerges and what guides their relative success and failure (Meyer and Minkoff 2004).

The important work of Cammaerts has begun the conversation over where political opportunity structures need to develop. Under what he has called the ‘mediation opportunity structure’, he has added media opportunities, network opportunities by way of access to communications technologies and social media, and discursive opportunities or what he refers to as ‘self-mediation by protest groups’ (Cammaerts 2012, 120–130). These helpful additions to political opportunities aid in uncovering how they manifest themselves during a protest group’s life cycle. In order to examine these in practice is to focus on the messaging and modes of communication used by protest groups. This is in line with Diani’s political message approach towards political opportunities. He argues that successful protest group messaging occurs within many different media and political contexts (1996, 1067). In other words ‘follow the message’.

Investigating the messages of protest groups is to examine the collective action frames contained in protester communications, both online and offline. These represent a protest group’s interpretation of an issue that is unfiltered by the mainstream media. The function of collective action frames in this context is to diagnose and define an issue as an ‘issue’, highlight the issues, and suggest potential solutions to a grievance (Gamson 2003; Sireau 2009; Smith et al. 2001; Wolfsfeld 2003; Snow and Benford 1992; Entman 1993). The technological advances in mobile and digital communication have increasingly personalised these action frames. Bennett uses Occupy’s ‘we are the 99%’ as an example of this type of framing, and the ability of the message to spread quickly across social media through images and personal stories through what he terms ‘connective action’ (Bennett and Segerberg 2012, 742). Furthermore, due to their in-built content limitations, the communication of messages via social networks means that connective action frames often require a simplistic language but remain straightforward enough to be understood and supported (ibid, 744). The use of digital communication as an alternative or complimentary to the mainstream media has come under increased scrutiny in recent years. This is since the perceived successes of social networking by Occupy, the 15-M movement in Spain and across the Middle East during the Arab Spring, to name by a few (Gaby and Caren 2012; Tremayne 2013; Hintz 2016; Hammond 2013; Fenton 2015; Gerbaudo 2012).

To bring these issues to public attention, protest groups utilise a number of different protest and media tactics (McAdam and Su 2002; Lipsky 1968; Eisinger 1973). The choice of protest tactics used by a group can have a major impact on the content and amount of press coverage. It has been argued by several academics that the more spectacular the protest tactics used, the greater the publicity a group will receive, but consequently the press will critically depoliticise the protest and empty out the context as to why a group is protesting (Rosie and Gorringe 2009a; Thomas 2008; Wykes 2000; Gitlin 1980; DeLuca 1999; Wahl-Jorgensen 2003).

The second key argument in this book is directly concerned with protest group messages and the representation of the protesters themselves, their aims and goals, and how they decided on their messages and media and protest tactics. There is a lot of research on the media coverage of collective action, but a lot less on why that particular type of action took place. Looking specifically at the decision-making process of protest groups allows a greater insight into the mechanisms behind the staging of a particular protest event. It gives greater context and helps to explain the reactions of the media and dominant institutions. The final argument takes the two points already outlined and relates them directly to the comparative success and failure of protest groups and the publicising of their messages. The combination of political and media contexts and a protest group’s aims adds to existing theories of what constitutes a successful protest action. The focus of these ideas suggests that protest groups want routine political access and influence, as well as media approval, not just coverage (Amenta, Carruthers, and Zylan 1992; Gamson 1990; Meyer 2004). In reality, the aims and goals of protest groups are more complicated than attempting to gain mainstream acceptance, and it is for this reason that the aims and goals of protest groups should be included in the analysis of collective action. This approach goes further than just examining the results of protest by media coverage and provides a more complete understanding of what influences the success and failure of protest groups.

Choosing the Case Studies

This next section will specifically detail each group and provide justification as to why they were chosen for analysis. Table 1.1 details the structural differences between the groups, their aims, the basis for their selection, outsider status, and the timespan under which the analysis had taken place. Taken further, what the selection of this wide mix of groups is trying to achieve is to make the underlying framework of the book applicable beyond the case studies presented within. The groups can be considered as having different focuses, be they local, national, or transnational, and by extension, they are each trying to reach different audiences in order to accomplish their specific aims. They span single-issue and multiple-issue protests, and they are all outsider groups who resort to a very public form of awareness raising to get support for their cause (Grant 1989). Furthermore, if we use Grant’s more nuanced topology of insider and outsider groups, then each of the case studies represents one of the three types of outsider identified by Grant (ibid):

• Potential insiders – aim to win close contact with government

• Outsiders by necessity – excluded from the political system because they lack the necessary resources

• Ideological outsiders – cannot be accommodated by the existing political system

The importance of highlighting these differences up front is that they alter the very nature of what a protest group’s aims are, and their relationship with their protest targets and with the media. This is what Hutchins and Lester talk of as being the “practical implications of this structural conditioning”, which impact upon the decision made within groups and the influence of the historical background to that specific type of group and tactics (2015, 344). Table 1.1 illustrates the different protest tactics and media strategies of these groups and presents an important and pressing opportunity to look deeper into the decision-making processes behind the collective action, and by extension the subsequent results of protest.

Methods and Materials Used

That being said, in order to address the myriad of complexities associated with not just one, but three different protest groups to build a detailed picture requires a wide range of methods and materials to be utilised. This aided in ascertaining the political opportunities available to each group, and to fully investigate the different parts of the mediation opportunity structure. As already mentioned, I used a ‘follow the message’ approach, which meant first ascertaining what each group’s collective action frames were and then ascertaining who they saw as the focus of blame, what solutions they suggested, and how they framed their own protest actions. To do this, each campaign’s online homepage and social media presence were examined, as was any physical material that was available, such as leaflets or newsletters.

Complimenting this approach and adding depth to the perceived collective action frames interviews were carried out with key members of each group: 3 from Save the Vulcan, 3 from Plane Stupid, and 2 from G20Meltdown. In addition, insights were given in interviews to non-mainstream publications and conferences by other members of the groups. The questions posed to the interviewees revolved around three main aspects of collective action: (1) the timing of protest action, (2) the choice of media and protest tactics, and (3) the adaptation of these strategies and tactics following the response of the media and dominant institutions. An ethnography was also carried out with the Save the Vulcan campaign, and the key was gaining access to participants. The participants were known to me and therefore a level of trust already existed. The group’s locality also made it easier to attend meetings and actions. The emphasis of the ethnography was placed onto full engagement and involvement in the group’s activities. This provided a greater insight into the media and protest tactics by allowing for greater access in the decision-making process.

Moving on from collective action frames and onto how the groups were represented by the press a content analysis was carried out to see how each group was framed. Newspapers are still an important source for media analysis because they are where debates around contentious issues and protest take place, and this reveals the “strategies of power or strategies for defining the rational and the commonsensical” (Wahl-Jorgensen 2003, 133–134). The online database Nexis was used to gather these reports, and rather than just searching for broad terms relating to the issues, the emphasis was placed onto each group’s name and the names of the members who appeared most often in press coverage. This meant that the scope of investigation stayed focused on the messages and protest tactics of specific groups, and removed the possibility of erroneous articles being gathered. The number of articles collected was 126 for the Save the Vulcan campaign, 207 for Plane Stupid, and 97 for G20Meltdown. The main difference however between these samples is that the Save the Vulcan newspaper stories were written in the Cardiff-based South Wales Echo and Western Mail outlets. This was because the Vulcan campaign was only mentioned four times in UK-wide publications. The local aspect to this is very much evident in the results of the content analysis explored more in chapter 3. The articles for Plane Stupid and G20Meltdown were taken from a full range of nationally available newspapers in the United Kingdom from tabloids to broadsheets and left- and right-wing ideologies.

Table 1.1 Background, Aims, and Justification for Studying Each Protest Group

The text-based nature of Nexis does miss the important visual characteristic of newspapers and the illustrative power of images. It is for this reason that physical copies of the newspapers were gathered where available, and this allowed the visual framing of the groups to be uncovered. The construction of a newspaper story and the image accompanying the report demonstrate the interplay between text and image and further highlight the...

Table of contents

- Cover-Page

- Halftitle

- 1 Introduction: Protest Groups and Contentious Politics

- 2 The Meaning of the Message and Repertoires of Protest

- 3 Case Study 1: Save the Vulcan – How to Save Pubsand Influence People

- 4 Case Study 2: Plane Stupid – Lights, Camera, Direct Action

- 5 Case Study 3: G20meltdown – More Than Just a March

- 6 Similarities and Differences between the Groups

- 7 Conclusion: Protest Opportunities

- References

- Index

- About the Author