Chapter One

Against Gargantua

The Study of Local Public Economies

The presumption that economies of scale were prevalent was wrong; the presumption that you needed a single police department was wrong; and the presumption that individual departments wouldn’t be smart enough to work out ways of coordinating is wrong.… For patrolling, if you don’t know the neighborhood, you can’t spot the early signs of problems, and if you have five or six layers of supervision, the police chief doesn’t know what’s occurring on the street.

(Elinor Ostrom, interviewed by Zagorski 2006)

I have seen the ways that police officers serving an independent community, where local citizens have constituted it, deal with citizens. Citizens are treated differently when you live in a central city served by a metropolitan police department. Many of the officers in very big departments do not see themselves as responsible to citizens. They are on duty for specific hours and with an entirely different mentality.… When you are in a police car for eight hours with officers from a big department, you learn that they really do not know the area they are currently serving since they rotate so frequently. When I was in a police car with an officer from a moderately sized department, they would start telling me about the local community, where there are trouble spots, and where few problems occur. They watch trouble spots that they see potentially emerging. They would sometimes take a juvenile to their home in order to discuss problems they are observing. They do not put kids in jail the first time they observe behavior that is problematic. In the big cities, officers tend to charge juveniles who have been seen to commit small offenses right away. Many jails are overcrowded with juveniles in large cities. Problems of law enforcement in central urban districts have grown over time and are linked to the way urban governance has been shifted to ever-larger units.

(Elinor Ostrom, cited by Boettke, Palagashvili, and Lemke 2013)

The first big impact that Elinor Ostrom and her team have had was thanks to their empirical study of local public economies. To the extent that people follow politics, it is usually the national-level politics that captures their attention. But, in many ways, the local level has a more direct impact upon our lives. The local-level issues tend to gather our attention mainly when something goes terribly wrong: police brutality in Ferguson, Missouri; poisoned drinking water in Flint, Michigan; the George Washington Bridge lane closure scandal in Fort Lee, New Jersey; the failure of public schools in Philadelphia; and so on. In many ways we don’t usually hear that much about local public economies because, by comparison to national-level policies, things actually tend to work much better. The Bloomington School’s work on local public economies helps explain why the local public sector usually works relatively well as well as why the failures that we observe have a specific pattern. When local politics fails, it does not fail at random.

The failure is usually a failure of scale: either due to an unfortunate top-down intrusion upon the local level or due to the inability of local communities to overcome the transaction costs involved in cooperating for producing larger-scale collective goods. In the relatively distant past, the second type of problem was much more prevalent than it is today. Historically, the emergence of the nation state acted as a means to solve the problems caused by over-decentralization. Nowadays, however, it is the top-down intrusion that usually causes most problems, which is why the Bloomington School, and this book, focuses more on it.

FROM UCLA TO INDIANA

The opening salvo of Bloomington School’s foray into the study of local public economies was a theoretical article written by Vincent Ostrom, Charles Tiebout, and Robert Warren in 1961, titled “The organization of government in metropolitan areas” (also included in McGinnis 1999b, chap. 1; and in V. Ostrom 1991b, chap. 6). This work was supported by the Bureau of Governmental Research at UCLA, the Haynes Foundation, and by the Water Resources Center of the University of California, but they were far from happy with the result. In fact, they had wanted the exact opposite conclusion. It was very common at the time to think that the consolidation of local administrations into larger centralized administrative units would increase efficiency, due to economies of scale and the elimination of overlapping efforts, as argued for instance by Anderson and Weidner’s book American City Government (1950). They were hoping for a study that would provide more academic support to these calls to centralize the administration in metropolitan areas. More specifically, they wanted something that supported the “Lakewood Plan”:

Ostrom was already interested by the implications of the 1954 incorporation of the city of Lakewood, California…which, in an unprecedented political bargain, would contract out the majority of its municipal services with Los Angeles County. The “Lakewood Plan,” as it came to be called, quickly became the model for succeeding contract cities in Los Angeles and nationwide. (Singleton 2015)

But, instead of going along with the fashionable view at the time, Ostrom, Tiebout, and Warren wrote a powerful defense of the benefits of decentralization and overlapping jurisdictions. Their intent was to use economic theory as a tool

for escaping political scientists’ “compulsion to want to superimpose a structure in such political situation[s].” As the research plan explained, in contrast with the political scientist: “The economist might apply a model of industrial organization and treat the interaction within the area as the operation of the market system, recognizing the existence of imperfect competition in an oligopolistic setting.”…[Ostrom and Tiebout] sought to place the organization of metropolitan governments in an explicitly economic framework, where municipal services were bought and sold in a “quasimarket.” This theorizing, however, drew the ire of other political scientists in the bureau, resulting in Tiebout’s and Ostrom’s removal from the project and the eventual joint authorship of an article with Robert Warren instead. (Singleton 2015)

To make matters worse from the point of view of the consolidationists, the article got published by the American Political Science Review, the top political science journal in the world, and became massively cited. Referring to the consolidationists as supporters of “Gargantua” probably didn’t help win them many favors either. The conflict with UCLA’s Bureau of Governmental Research eventually led both Vincent Ostrom and Charles Tiebout to leave the university. Their initial intention was to go beyond just theory, but the conflict with the bureau prevented it:

The Lakewood Project—the study of the contract system in Los Angeles—will be approached in light of the model furnished by economics. Rather than as a limited examination of relations between political units, this study will evaluate the performance of the county government as a seller of goods and services, and of particular local units as the buyers of these services, as unions organized to meet the demand of consumers (the citizens). (“An Approach to Metropolitan Areas,” Research Seminar Minutes, September 23, 1959, UCLA’s Bureau of Governmental Research, cited by Singleton 2015)

This empirical program will be revived in the 1970s by Elinor Ostrom and her students. On the theoretical side, “[Vincent] Ostrom wanted to adapt the Lakewood project research into a book, titled ‘A New Approach to the Study of Metropolitan Government’…though it never materialized” (Singleton 2015). He did, however, develop the polycentricity concept further (V. Ostrom 1972, 1991a). Robert Warren finished his dissertation under Vincent Ostrom and published some of the Lakewood project findings together with his theoretical analysis (1966).

Historically, metropolitan areas emerged in an unplanned fashion as small towns gradually grew up to the point where they reached one another, and combined into one de facto, but not de jure, large urban area. The administrative organization of these metropolitan areas remained decentralized because of their history. The question was: Should they now be centralized under a larger hierarchical system? The de facto organization was “polycentric” reflecting the “multiplicity of political jurisdictions in a metropolitan area” (V. Ostrom, Tiebout, and Warren 1961). Should this be changed? Polycentricity became an important concept, and it was the topic of Elinor Ostrom’s Nobel Prize address (2010a) because it not only merely describes the de facto situation, but can also be used to understand why the system works relatively well, in the sense that it has desirable emergent, unplanned properties.

Polycentricity was first defined as a system of “many centers of decision making that are formally independent of each other” (V. Ostrom, Tiebout, and Warren 1961), but which, nonetheless, are forced to interact in both competitive and cooperative fashions, and may be embedded into larger systems: the decision centers “take each other into account in competitive undertakings or have recourse to central mechanisms to resolve conflicts,” and, as a result, “the various political jurisdictions in a metropolitan area may function in a coherent manner with consistent and predictable patterns of interacting behavior” (V. Ostrom, Tiebout, and Warren 1961).

Once they moved to Indiana University and started the workshop, they were able to return to the initial idea. Initially, Elinor Ostrom was hired for teaching “Introduction to American Government” on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays at 7:30 a.m. “How could I say no?” she joked later (Zagorski 2006). But the position eventually changed to a tenured one, and when she started having PhD students in the 1970s, she told them to pick up any empirical topic except groundwater, as she was tired of that subject after having done her dissertation on it (this was only temporary). At the suggestion of Roger Parks, they chose to study police departments. This was not an entirely foreign subject to Elinor Ostrom. As a graduate student, she had been a part of Robert Warren’s team in Vincent’s Lakewood Project.

Building on Ostrom, Tiebout, and Warren’s theoretical article and on the initial idea behind the Lakewood Project, a large number of empirical studies followed (Bish 1971; Bish and Kirk 1974; Elinor Ostrom 1976b; Elinor Ostrom, Parks, and Whitaker 1978; Bish and Ostrom 1979; V. Ostrom, Bish, and Ostrom 1988; McGinnis 1999b; see also Aligica and Boettke 2009 for more on the social philosophy behind these studies). As Roger Parks recalls (included in McGinnis 1999b, 349),

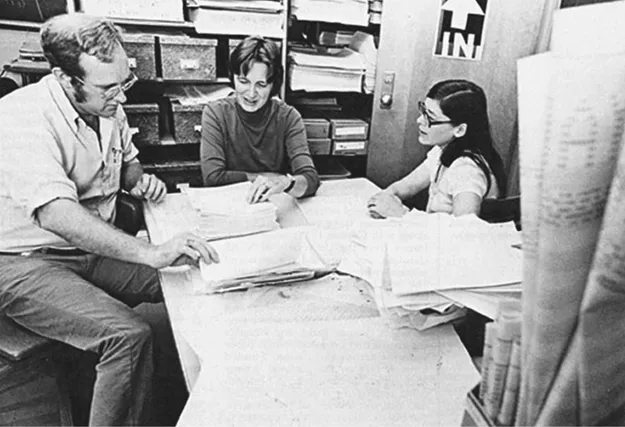

In the spring of 1970, an intrepid band of graduate and undergraduate students, ably led by Lin Ostrom, set forth on the streets of Indianapolis and its close suburbs. Their task was to collect data relevant to the question of whether police services were better supplied by large, highly professionalized bureaus or by much smaller departments characteristic of most suburban United States. In the face of recent [then] and recurring recommendations for consolidation of police forces, other public services, and local governments in urban areas, this venture seemed quixotic, but it was instead quite productive. From it sprang a stream of Workshop ...