eBook - ePub

Entrepreneurship and Institutions

The Causes and Consequences of Institutional Asymmetry

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Entrepreneurship and Institutions

The Causes and Consequences of Institutional Asymmetry

About this book

Entrepreneurship does not occur in a vacuum. The institutions which provide the framework for economic activity matter. As countries around the world strive for economic growth, this book examines how institutional arrangements are critical in fostering entrepreneurship. Through 12 case studies drawn from Asia, Europe and America the book demonstrates how different institutional arrangements impact the nature, scope and scale of entrepreneurial activity. Each chapter highlights how the prevailing formal and informal institutional arrangements interact, and how this has consequences for the development of more entrepreneurial economies. By synthesizing empirical and theoretical insights the book explores how fostering more entrepreneurial economies is as much a question of institutional alignment as it is the creation of more supportive formal and informal institutions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Entrepreneurship and Institutions by Nick Williams,Tim Vorley,Colin Williams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Entrepreneurship. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

Entrepreneurship and institutional asymmetry

Entrepreneurship is widely acknowledged as an engine of economic growth (Acs et al., 2008). However, not all entrepreneurship leads to growth (Sautet, 2013), and the context in which entrepreneurial activity occurs is of critical importance in determining the productive potential of entrepreneurial action (Williams and Vorley, 2015a). In understanding the nature of ‘context’ one of the key analytical concepts used is that of the ‘institution’. While exact definitions of what constitutes institutions differ, there is a broad consensus that they include both frameworks of specific rules that regulate behaviour (e.g., laws which govern economic activity), referred to as formal institutions, and common and shared understandings (e.g., cultures, norms and values), referred to as informal institutions. The nature of institutions and institutional arrangements serves to define the institutional context and shapes economic and social outcomes. In this way, institutions provide both meaning and context to actions and activities. This book addresses how institutions and institutional arrangements shape the nature of entrepreneurial activity. The entrepreneurial capacity of a nation is often defined in terms of formal institutions within a country (North, 1990). Yet while formal and informal institutions are often examined separately, it is the interaction between the two which is crucial for economic development. Indeed, this book shows that it is the interplay between formal and informal institutions that is of critical importance in enabling and constraining entrepreneurial activity as well as determining the nature of entrepreneurial productivity.

Institutions evolve over time as rules and perceptions change. As such, it is important to understand institutions in their historical context. Baumol (1990) exemplifies this through analyses of ancient Rome, medieval China and England in the Middle Ages. He finds that the institutional structure in ancient Rome was weighted towards a culture pursuing wealth through landholding, usury and political moneymaking, rather than involvement in industry or commerce; that although China was technologically advanced the economy remained stagnant due to the continuous curtailment of economic activity by government; and that in England, a period of sustainable economic growth lasting centuries was seen as resulting in the incentives being weighted towards productive entrepreneurship (Baumol, 1990). Such insights allow institutions to be ‘observed, described, and, with luck, modified and improved’ (Baumol, 1990, p. 894). Institutional change that is introduced indigenously, that is, by the citizens of a country, and evolves endogenously, that is, by the results of the interaction of individuals and is not devised centrally by government, is most likely to persist over time (Boettke and Fink, 2011). Endogenously evolved institutions are in this sense relatively ‘sticky’ because they are based on the existing institutions and beliefs (Boettke et al., 2008). In contrast, institutions exogenously introduced, or imposed, by government are likely to be less sticky, while change implemented by foreign government entities is least likely to stick, since members of foreign governments are unfamiliar with the indigenous institutions and beliefs (Boettke and Fink, 2011).

As institutions evolve, the interplay and relationship between the formal and informal are critical if entrepreneurship is to be supported. Where the formal and informal complement each other, entrepreneurial activity will be fostered; conversely, where there is asymmetry, entrepreneurial activity will be stymied (Williams and Vorley, 2015a). The extant literature on institutions argues that formal and informal institutions interact in two key ways, with formal institutions either supporting (i.e., complementing) or undermining (i.e., substituting) informal institutions (North, 1990; Tonoyan et al., 2010; Estrin and Prevezer, 2011). Informal institutions are complementary if they create and strengthen incentives to comply with the formal institutions, and thereby plug gaps in problems of social interaction and thus enhance the efficiency of formal institutions (Baumol, 1990; North, 1990). Where informal institutions substitute for formal institutions, individual incentives are structured in such a way that they are incompatible with formal institutions, and this often exists in environments where the formal institutions are weak or not enforced (Estrin and Prevezer, 2011). The interactions between formal and informal institutions present a key challenge for policy makers who seek to foster entrepreneurship by changing the ‘rules of the game’ and the prevalent culture. This chapter begins by setting out the current state of literature on institutions and entrepreneurship, including how formal and informal institutions are defined. It then examines the importance of the interplay between formal and informal institutions, focusing specifically on the causes and consequences of institutional asymmetries.

THE NATURE OF INSTITUTIONS

Research on entrepreneurship has increasingly taken into account the nature of the institutional framework (Ahlstrom and Bruton, 2010; Estrin and Prevezer, 2011). This book advances institutional research through the development of a better understanding of the institutional environment, by focusing on the interplay between formal and informal institutions. The emergence of asymmetries in institutions has the potential to undermine entrepreneurial activity. Although reforms to formal institutions may be a positive step in fostering entrepreneurship, if they are not congruent with informal institutions, then economic development within a country will not be positively affected (Williams and Vorley, 2015a).

Formal institutions

Formal institutions can be defined as the rules and regulations which are written down or formally accepted, and give guidance to the economic and legal framework of a society (Tonoyan et al., 2010; Krasniqi and Desai, 2016). Where formal institutions are strong and well enforced, over time entrepreneurial activity can be fostered productively and in turn contribute to economic growth (Acs et al., 2008). However, where formal institutions are weak, they can impose costly bureaucratic burdens on entrepreneurs, and this increases uncertainty as well as the operational and transaction costs of firms (Djankov et al., 2002; Puffer et al., 2010).

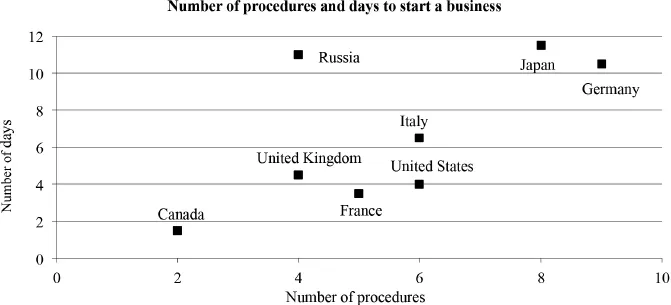

Developed economies are often characterized as having stable institutional environments, which make it easy to start and grow a business. The United States is often cited as the exemplar of a low-regulation economy, with formal institutions being conductive to and supportive of entrepreneurial activity. This has influenced policy elsewhere, for example, in the European Union, where the Lisbon Strategy attempted to create a ‘friendly environment’ for starting and developing a business, and which had the implicit desire to shift the European economy to be more like the United States (Atherton, 2006). Yet despite this exemplar status, the latest data from the World Bank’s ‘Doing Business Survey’, which measures various aspects of formal institutions, including the ease of starting a business, access to credit, property rights and payment of taxes, finds that New Zealand has the most efficient formal institutional environment. The United States is placed eighth, behind the United Kingdom in seventh (World Bank, 2016). Figure 1.1 compares the G8 nations on two of the key World Bank measures: the number of days and the number of procedures it takes to start a business. It shows that Canada has the most effective formal institutions for starting a business, requiring entrepreneurs to undertake one procedure which takes 1.5 days on average to launch a venture.

Figure 1.1. Ease of starting a business among G8 nations. Source: World Bank (2016).

While the ease of starting a business is a proxy for formal institutions, it does not capture the complexity of the formal institutional environment. Despite this, however, a positive link has been identified between economic growth and entrepreneurship in developed economies, where it is easy to start a business, while the same relationship has not been established for developing economies (Sautet, 2013). A key reason for this is explained by the lack of effective formal institutions in developing economies (Williams and Vorley, 2015a). Entrepreneurs in weak formal institutional environments, for example, in transition economies which have moved from centralized planning to more open market conditions, can often be faced with incoherent and/or constantly changing regulations (Manolova and Yan, 2002; Aidis et al., 2008), meaning that they are not able to plan effectively (Tonoyan et al., 2010). While a stable legal framework with well-protected property rights can promote planning and coordination (Boettke and Fink, 2011), as well as prevent the ad hoc expropriation of the fruits of entrepreneurship (Henrekson, 2007), the experience in many developing economies has been that the legal system has been incapable of adequately enforcing laws and of resolving business disputes (Manolova and Yan, 2002). This is despite many former centrally planned economies having adopted legal frameworks similar to those of more developed economies, including laws relating to property, bankruptcy, contracts and taxes; but they have been inefficient in implementing them (Smallbone and Welter, 2001; Aidis et al., 2008). Due to these inefficiencies, going to court to settle a business dispute can be both time-consuming and costly. In addition, perceptions that the institutions are often corrupt means that many entrepreneurs will avoid turning to the courts to settle disputes (Tonoyan et al., 2010). In such environments, entrepreneurs will often turn to informal networks to compensate for the weakness (or failures) of formal institutions, for example, by using connections to bend the rules or paying bribes that break them (Aidis and Adachi, 2007). Another challenge is gaining credit in such economies, as banks favour larger businesses and lack the willingness to finance small enterprises (Smallbone and Welter, 2001). Accessing credit is a major constraining factor for entrepreneurial activity in transition countries, and as a resort small firms often either have to turn to the informal credit, for example, borrowing money from family and friends, or bribe bureaucrats to secure the access to capital (Guseva, 2007).

Formal institutions can also be challenging for entrepreneurs in crisis-hit economies, with changes created either internally by policy makers or externally by pressures from supranational agencies (Williams and Vorley, 2015b). For example, Smallbone et al. (2012) demonstrate how a credit crunch caused by the recent economic crisis impacted on both the supply of and demand for small firm financing in the United Kingdom and New Zealand, and Cowling et al. (2012) show that the crisis in the United Kingdom led to finance being more readily available to larger and older firms throughout the recession. Unsurprisingly, finance has become more difficult to obtain in Greece as a result of the endemic and ongoing crisis (European Commission, 2012), reflecting a deterioration in the formal institutional framework (Williams and Vorley, 2015b). Such challenges mean that entrepreneurs have to respond to uncertain formal institutional changes, and often this means tempering ambitions for their venture, shutting the venture down or moving some or all of the activities into the informal economy.

Informal institutions

While business start-ups are often used as a proxy for entrepreneurship, they represent only one of the many outcomes of entrepreneurial activity (Huggins and Williams, 2009). The phenomenon of entrepreneurship is largely a phenomenon of the mind, concerning alertness to opportunity, perception and imagination (Kirzner, 1973) and is a behavioural characteristic of individuals expressed through innovative attributes, flexibility and adaptability to change (Wennekers and Thurik, 1999; Swedberg, 2000). As Sautet and Kirzner (2006, p.17) suggest, culture shapes ‘what an individual perceives as opportunities and thus what he overlooks, as entrepreneurship is always embedded in a cultural context’, and as a result culture plays a key role in fostering entrepreneurship (Huggins and Williams, 2009). Despite its importance to economic development, what constitutes culture is often vague (Olson, 1996); however, through examination of informal institutions it is possible to understand the prevalent norms and values which enable and constrain entrepreneurial cultures.

Informal institutions can be defined as the traditions, customs, societal norms, culture, unwritten codes of conduct (Baumol, 1990; North, 1990; Smallbone et al., 2012). Norms and behaviours present within a society define and determine models of individual behaviour based on subjectivity and meanings that affect beliefs and actions (Bruton et al., 2010). These norms and values are the often taken-for-granted, culturally specific behaviours that are learnt living or growing up in a given community or society (Scott, 2007) and engender a predictability of behaviour in social interactions. Over time, these norms and values are reinforced by a system of rewards and sanctions to ensure compliance and themselves become an informal institution (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983).

Understanding informal institutions is important to entrepreneurship in terms of how societies accept entrepreneurs, inculcate values and create a cultural milieu whereby entrepreneurship is accepted and encouraged (Bruton et al. 2010). Indeed informal institutions are widely acknowledged as critical to explaining different levels of entrepreneurial activity across countries (Davidsson, 1995; Frederking 2004; Puffer et al., 2010). Since entrepreneurship is always embedded in a cultural context, understanding informal institutions is critical to fostering entrepreneurship (Williams and Vorley, 2015a). Yet despite the importance attributed to culture in relation to entrepreneurship and economic development, it remains an elusive concept (Huggins and Williams, 2011). This elusiveness represents a substantive challenge for academics and policy makers alike, as affecting cultural change demands a clear understanding as to the intended objectives of such interventions and the mechanisms by which they are achieved. Where informal institutions within a society are not well understood or adequately considered by policy makers, then institutional reforms will have a limited overall impact on fostering entrepreneurship.

More developed open economies are often considered to have informal institutions that are pro-entrepreneurship, with norms and values supportive of pursuing entrepreneurial opportunities and view entrepreneurial activity positively. Common examples such as Silicon Valley and Route 128 in Boston demonstrate how through shared norms and values an entrepreneurial culture can be both fostered and sustained (Saxenian, 1996). By contrast, developing economies often lack the norms and values which are considered to create positive entrepreneurial cultures in more developed economies. The demise of socialist systems in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union has seen dramatic changes in political, economic and juridical institutions. However, the many norms and values in these transitional economies learnt and adopted during the socialist years remained engrained and largely unchanged (Vorley and Williams, 2016). Indeed, Winiecki (2001) states that modern history offers no better field to test the interaction of changing formal rules and prevailing informal rules than Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. These countries are characterized by informal institutions which have substituted for, rather than complementing, changes in the formal institutional environment (Guseva, 2007; Estrin and Prevezer, 2011). Moreover, in environments with un(der)reformed and weak formal institutions, such as transition economies, entrepreneurial activity is typically guided and governed by informal codes of conduct (Ahlstrom and Bruton, 2002). As a result existing research has shown that entrepreneurial behaviours in many transition economies are often shaped by the informal institutions inherited from socialist regimes, with unwritten codes, norms and social conventions dominating everyday practice (Ledeneva, 1998).

Reforms in developing economies often focus on formal institutions (Manolova and Yan, 2002). In transition economies, liberalisation was expected to create new and numerous opportunities for entrepreneurship (Saar and Unt, 2008). Yet often there has not been a corresponding shift in informal institutions which has stymied entrepreneurship (Williams and Vorley, 2015a). In many ways, reforms to the formal environment are undertaken with little or no consideration as to the depth and importance of informal institutions. While reforming informal institutions is possible, it is often a slow process, since the norms and values passed from one generation to the next can be resistant to change (Winiecki, 2001). Indeed, Estrin and Mickiewicz (2011) assert that changes in informal institutions can take a full generation to occur. It is important to note, however, that there are some examples of successful changes to informal institutions. For example, Georgia’s institutions have changed leading to improvements in their World Doing Business rankings (World Bank, 2016), while at the same time perceptions of opportunity have improved, with social values towards entrepreneurship higher than in many EU and non-EU countries (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 2015).

As entrepreneurship becomes more visible and valued in society it gains legitimation, and the growth of entrepreneurial attitudes, ambition and perspectives in turn serves to reinforce the emergence of a positive entrepreneurial culture (Minniti, 2005). In this sense, although government is clearly important in shaping the institutional environment and influencing entrepreneurial activity (Smallbone and Welter, 2001; Acs et al., 2008), the remit for institutional change is beyond the purview of policy makers alone, although they too can help foster a more entrepreneurial culture (Williams and Vorley, 2015a). Entrepreneurs themselves can also act as change agents and influence the institutional landscape (McMullen, 2011). Culturally, entrepreneurship is reinforced by informal institutions as individuals follow social norms and are influenced by what others have chosen to do. Therefore in order to reform informal institutions and promote a more entrepreneurial culture, Verheul et al. (2002) refer to the importance of a positive feedback cycle whereby people see others succeeding as entrepreneurial activity and are motivated to be more entrepreneurial. In consequence, over time, informal institutions can be influenced and improved, and entrepreneurs’ actions can contribute to wider societal change and economic development (Welter and Smallbone, 2011).

THE CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES OF INSTITUTIONAL ASYMMETRY

Economic growth will be held back when formal and informal institutions are not aligned. This occurs when the formal rules do not reflect the informal norms of conduct and vice versa. In such cases, formal institutions cannot be enforced properly, and the informal norms take priority, thus making enforcement of rules difficult and costly (De Soto, 1989). As formal institutions they affect people only if they are enforced, as otherwise the asymmetry can result in rules and regulations being circumvented by informal institutions (Williams and Vorley 2015a). Figure 1.2 depicts how formal institutions are costly to enforce, while informal institutions are self-enforced. Where there is overlap between the two, formal rules and informal norms complement each other and are thus easy to enforce.

Williamson (2009) demonstrates how institutions operate at different levels and influence each other, with informal institutions often emerging spontaneously but influenced by the calculative construction of formal rules. Formal rules are mediated by interaction with informal norms, and the economic outcomes of these interactions change over time (Winiecki, 2001), with norms affecting how rules are designed and implemented and whether they are followed. As noted previously, this has been reduced to two key interaction dynamics: the complementary and the substitutionary.

In this book, we develop the concept of institutional asymmetry to describe the interaction between formal and informal institutions. We define institutional asymmetry as a misalignment between formal and informal institutions. The asymmetry can develop over time as formal institutions are reformed to support entrepreneurship, while informal institutions remain unsupportive, or changes in informal institutions remain incompatible with formal institutions. Alternatively, asymmetry can reduc...

Table of contents

- 1 Introduction: Entrepreneurship and institutional asymmetry

- PART I: EUROPE

- PART II: ASIA

- PART III: AMERICAS

- PART IV: CONCLUSIONS

- References

- Index

- About the Authors