![]()

Chapter 1

Norms of citizenship

Jan W. van Deth

CITIZENSHIP AND DEMOCRACY

Probably no society can exist on the basis of power and control only – without some minimum level of acceptance of its basic arrangements by its members, the future of any society is endangered. With their reliance on consensus, peaceful settlements and respect for minorities in particular, the persistence of democracy depends on citizens’ support of basic virtues. Democratic virtues are usually associated with the image of a ‘good’ citizen, that is, with the notion of an ideal citizen in a world deprived of practical limitations. Such a ‘good’ citizen is, for example, considered politically and socially engaged, obeying the laws or caring for less-fortunate fellow men. Each aspect of this idealised citizen can be easily formulated as a norm of citizenship. For the persistence of democracy, the crucial question, then, is not whether citizens are always active, obedient and solidary, but rather the extent to which they support these norms. Not without reason David Easton emphasised long ago that for the persistence of political systems ‘the existence of covert support, or supportive states of mind, is far more important than its actual expression in overt behaviour’ (1965: 161).

Several norms of citizenship appear to be widely shared in established democracies. Data from the Citizenship, Involvement, Democracy project and from the European Social Survey show high levels of support especially for law obeying, solidarity and individual autonomy. Between 70 and 90 per cent of the populations in European countries consider these three aspects ‘very important’ features of a ‘good’ citizen. A similarly high level of support can be revealed for the norm to cast a vote in public elections. Much lower, however, is the support for the norm to be active in voluntary organisations (Roßteutscher 2004; van Deth 2007, 2013; Denters et al. 2007; Bolzendahl and Coffé 2013). The Tocquevillean idea that engagement in voluntary associations is an important aspect of being a ‘good’ citizen is supported by about one out of every four respondents only. Even more remarkable is the clear lack of support for the idea that a ‘good’ citizen should be active in politics: only 10 per cent of the people support the norm that a ‘good’ citizen is – generally speaking – a politically active citizen. Schudson’s description of the rise of ‘monitorial citizens’ in modern democracies who ‘tend to be defensive rather than proactive’ and are reluctant to get involved in public and political affairs beyond voting seems to fit this image nicely (1998: 311).

Apparently, many citizens have a clear notion of the most important features of an ideal, ‘good’ citizen and they differentiate their support for distinct norms of citizenship accordingly (van Deth 2007). The consistent differences in support for various aspects of a ‘good’ citizen and the evident cross-national differences in these distributions suggest that support for norms of citizenship is fairly persistent and relatively unaffected by individual or contextual factors. Yet no empirical evidence is available to corroborate these expectations. As Denters and van der Kolk remark, ‘A clear picture on the sources of citizenship is lacking’ (2008: 155). In this chapter the images of a ‘good’ citizen and the development of these orientations among adolescents and young adults in Belgium over a five-year period are explored. First, support for several norms of citizenship is described and summarised in three main types: politically, socially and duty-based citizenship. Second, both the main antecedents and the predictors for these three types are determined. By dealing with these two points, the spread and development of images of a ‘good’ citizen among young Belgians during their transition from adolescence to adulthood are revealed. The main conclusion is that the two engaged types of citizenship are incorporated in attitudinal syndromes with recursive associations instead of relationships with clear causal paths. Besides, support for duty-based citizenship is relatively difficult to explain although especially these norms are strongly supported by young people in Belgium.

SUPPORTING NORMS OF CITIZENSHIP

The concept ‘citizenship’ defines the relationships between citizens and the state in terms of their respective rights and duties. Political philosophers from Aristotle and Plato to Michael Walzer and Benjamin Barber have dealt with these relationships and debated accompanying definitions of rights and duties. In democracies people have to meet the requirements of democratic life, which include, for example, that they participate in public and political affairs, are willing to accept responsibility for public tasks and decisions, be tolerant and solidary and defend individual rights and equal opportunities. In fact, the very recognition of these requirements transforms people living in some society or state into citizens living in a democratic polity. Understood in this way, citizenship, by definition, is democratic citizenship. Although one could think of people living under non-democratic regimes as citizens without rights and duties, the concepts democracy and citizenship are mutually dependent and presume each other (van Deth 2007).

Even if we restrict citizenship to democratic citizenship, many types of rights and duties have been distinguished (see Janoski 1998). The most important aspects of citizenship can be summarised by defining norms or ideals that an imaginary ‘good’ citizen is expected to fulfil in order to foster democracy. Which norms characterise such a ‘good’ citizen? Very interesting information about the ways people think about citizenship and the language they use to articulate normative ideas is provided by Pamela Johnston Conover and her collaborators (Conover et al. 1991, 1993, 2004). The results of their extensive discussions with British and American focus groups show that a ‘good’ citizen understands his or her rights mainly as civil rights (United States) or social rights (Britain) and does not consider political rights to be equally important (both countries). Duties are mainly conceived as responsibilities required to preserve civil life. A ‘good’ citizen surely values social engagement and active involvement in community matters, but citizens do not agree about the main reasons for these activities. Moreover, sophisticated arguments about the need for social concern and collective actions are frequently mentioned. Survey research among representative samples of the populations of various countries cannot uncover motivations and arguments of people as focus group discussions allow us to do. Yet the results of several large cross-national surveys corroborate the main findings of these discussions and, more importantly, show that many citizens have clear ideas about the norms that a ‘good’ citizen is expected to meet in a democracy (Roßteutscher 2004; van Deth 2007; Denters et al. 2007; Dalton 2008b; Bolzendahl and Coffé 2013).

Structured responses to questions about support for distinct norms of citizenship suggest that ideas about a ‘good’ citizen are persistent and relatively unaffected by individual or contextual factors. The genesis and development of these norms, however, are still largely white spots on the map of attitudinal requirements for a vibrant democracy. The Mannheim study of political orientations among young children in their first year in primary school shows that children at age six or seven are already able to express clear ideas about desirable aspects of a ‘good’ citizen with high levels of endorsement for socially desirable qualities such as helpfulness, hard work and law-abidingness (van Deth et al. 2011: 156; Abendschön 2010: 119–22; see also Hess and Torney 1967: 37–38; Moore et al. 1985). Apparently, support for distinct norms of citizenship is already available at a very young age and meaningful patterns can be detected in these orientations long before children start to think of themselves as citizens. Somewhat older children and youngsters probably will reconsider their normative orientations when their cognitive skills and competences are enhanced and the impact and relevance of societal and political arrangements becomes more evident. These expectations are impressively corroborated by Oser and Hooghe (2013) in their analyses of support for norms of citizenship among fourteen-year-old students in Scandinavia. What still seem to be missing, however, are empirical findings for the transitory phase from adolescence to young adulthood. Especially this period – the transformation to full citizenship – can be expected to show a re-evaluation and confirmation of normative orientations acquired earlier in life.

The Belgian Political Panel Survey 2006–2011 (BPPS) is a three-wave panel survey of Belgian youngsters (from both the French and Dutch-speaking communities; see Hooghe et al. 2011) who were interviewed at ages sixteen, eighteen and twenty-one. In the first wave, a representative sample of 6,330 young people in secondary school (fourth year of secondary school or tenth grade), representative of the academic tracks in each school participated in the study. A total of 3,025 respondents were interviewed in all three waves, enabling us to follow the political orientations among young people during a critical phase in their life. As in several other studies, support for norms of citizenship is measured in the BPPS by presenting a number of qualities that an ideal, ‘good’ citizen is expected to have:

‘In a democracy being a good citizen means:

- 1) Supporting people who are less fortunate than yourself

- 2) Casting a vote

- 3) Obeying laws

- 4) Volunteering in some organisation

- 5) Being active in politics

- 6) Reporting a crime if you see one

- 7) Following political news

- 8) Committing yourself to the neighbourhood’.

Responses range from ‘completely unimportant’ (0) to ‘very important’ (5).

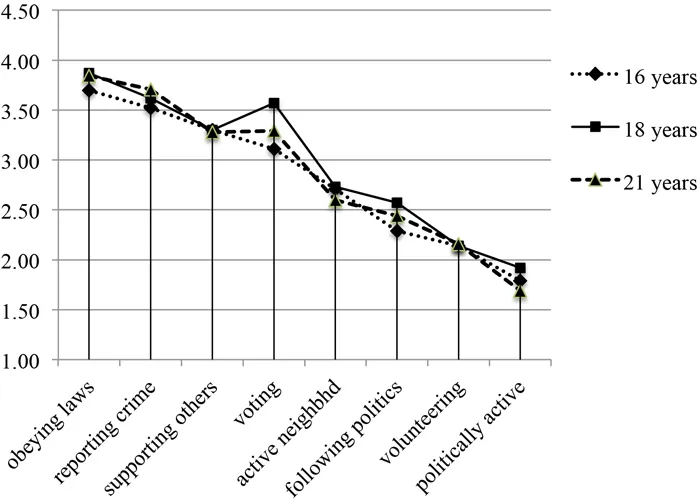

Mean levels of support for the eight aspects of being a ‘good’ citizen youngsters in the three waves of the BPPS are depicted in figure 1.1. Several conclusions can be drawn from these results. First, the level of support is clearly different for various norms of citizenship, ranging from very high levels for law-abidingness and reporting crime (averages above 3.5) to rather low levels for volunteering and being politically active (averages about 2 or lower). Young people do not attach much importance to social and political activities beyond voting – obedience and solidarity are much more important to characterise a ‘good’ citizen. This finding is clearly in line with results of studies among adults (see van Deth 2007). Apparently, support for different norms of citizenship varies among the population, and young people are no exception when it comes to attributing less importance to volunteering and political activities. Second, average levels of support for most aspects of a ‘good’ citizen are almost identical in each of the three waves, suggesting that norms of citizenship barely change during the transition to adulthood. Yet one item noticeably deviates from this pattern: whereas the importance attached to casting a vote increases clearly when young people obtain the right to vote at age eighteen, the support for this norm largely returns to its initial level in the next few years. The acquisition of suffrage seems to establish a major event in the development of political orientations among young people that results in a strong upgrading of the importance of voting as an aspect of a ‘good’ citizen. The subsequent decline underlines the novelty of having the opportunity to cast a vote for the first time in life that incites the clear increase at age eighteen.

Figure 1.1. Support for aspects of a ‘good’ citizen (means 0–5)

DIMENSIONS OF NORMS OF CITIZENSHIP

A ‘good’ citizen probably can be characterised by a large number of aspects, and the eight items used in the BPPS cover various important norms. These items might reflect one or more underlying dimensions of norms of citizenship that could reduce the available information in the eight items in a theoretically meaningful way. Briefly reviewing the literature on citizenship Denters, Gabriel, and Torcal notice that there is ‘a considerable overlap among competing conceptions of good citizenship’ (2007: 92) and that, more importantly, main aspects can be covered by a relatively low number of items. Several authors presented such underlying structures and dimensions of norms of citizenship. In their seminal work on citizenship in Sweden, Petersson and his colleagues (1998: 129–30) used a large set of items covering four dimensions: participation, deliberation, solidarity and law-abidingness. For European countries Denters, Gabriel, and Torcal (2007) presented a common pattern of three dimensions: ‘Law-abidingness’ (paying taxes, obeying the law), ‘solidarity’ (help others, think of others) and ‘be self-critical’ (form own opinion, be self-critical). As expected, these dimensions clearly overlap in many countries, but only the norm ‘to be self-critical’ loaded frequently on other dimensions as well (Denters et al. 2007: 93). The questions about norms of citizenship included in the first wave of the European Social Survey has been generally interpreted as covering two dimensions, but different authors prefer different tagging and item selection. Whereas Roßteutscher (2004: 187) labels her two dimensions ‘representative citizenship’ (casting a vote, obeying law, form own opinion, support people worse of) and ‘participatory citizenship’ (volunteering, active in politics), Denters and van der Kolk (2008: 141) delete the indistinct item (support other people) from their factor analyses and depict the two dimensions as ‘liberal’ and ‘classical’ conceptions of citizenship, respectively. Particularly the analyses of US data by Dalton (2008a, 2008b) have stimulated the debate on citizenship and its main dimensions. In his study of aspects of a ‘good’ citizen he clearly reports two dimensions, which are labelled ‘citizen duty’ and ‘engaged citizen’. The first dimension reflects traditional notions of citizenship understood as the responsibilities of a citizen-subject and is based on the support for such norms as casting a vote, paying taxes, obeying the law, watching the government and serving in the military. The second dimension reveals a pattern of an engaged citizen who claims the right to bring in his or her own ideas, who is willing to act on his or her own principles, who is aware of others and who is willing to challenge political elites (Dalton 2008b: 27–28). Specifically, an ‘engaged citizen’ supports such norms as following his or her own opinions, helping people worse of, being active in politics and voluntary groups and choosing products deliberately. Although the available sets of items are not identical the distinction between the two types of citizenship presented by Dalton also underlies the two dimensions Roßteutscher and Denters et al. detected. It does not come as a surprise, therefore, that Coffé and van der Lippe (2010) were able to reproduce measures for engaged and duty-based citizenship in another analysis of the first wave of the European Social Survey.

In spite of the broad empirical corroboration of the idea that norms of citizenship can be summarised in a low number of more general aspects or dimensions some studies report complications with data reductions and, therefore, stick to the analyses of norms of citizenship separately (Bolzendahl and Coffé 2013: 65 and 69). To explore the opportunities for data reduction and dimensions of citizenship in the BPPS data, a factor analysis (principal component analysis [PCA]) of the scores for the eight items is performed. The results of these computations are summarised in table 1.1 revealing a clear – and very similar – three-dimensional structure in each of the three waves of the panel with acceptable levels of explained variance (R2) and measures of sampling adequacy (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Test [KMO]). Apparently, not only the levels of support for the distinct norms of citizenship appear to be remarkably persistent (see figure 1.1), but also the structure underlying these scores remains more or less the same during the transition from adolescence to early adulthood. Furthermore, rather straightforward labels are suggested for each of the three dimensions. The first dimension covers all three political items and can be labelled as the ‘politically engaged’ type of citizenship. Since the three items on the second dimension refer to social activities dealing with vo...