![]()

1

WILLIAM BUCKHURST AND EARLY SOUTH MELBOURNE

Australian historians tend to view the growth and development of Melbourne in isolation, focusing on local issues such as the rival claims of John Batman and John Pascoe Fawkner to be declared the founder of the city. Taking a global view, however, the foundations of Melbourne, Sydney, Hobart and Brisbane were part of a remarkable wave of urbanisation that led to the foundation and rapid growth of European cities around the Pacific Ocean during the 19th century. The new cities in Australia were matched by the likes of Auckland, San Francisco, Seattle and Vancouver, all of which were the commercial centres for rich hinterlands newly opened to European settlement after the displacement of indigenous inhabitants. Of all these cities, Melbourne quickly became the largest, both in population and physical extent.

All Australian capital cities except Melbourne and Adelaide were founded as convict settlements, and the legacy of the ‘convict stain’ has long been debated. Melbourne was established by private speculators and, at least until the great crash of the 1890s, contemporary observers believed it was marked out from other Australian cities by its entrepreneurship and ‘get ahead’ spirit, as well as its rapid growth.1

In June 1835, when John Batman signed a ‘contract’ with eight Aboriginal chiefs to ‘buy’ half a million acres of land on the northern shores of Port Phillip Bay, he described the land as ‘the most beautiful sheep pasturage I ever saw in my life’. Sailing six miles up the Yarra River, he ‘found the River all good water and very deep. This will be the place for a village.’ 2 At the end of August 1835 a settlement was founded by an expedition organised by John Pascoe Fawkner, and the first modest dwellings were built in what is now the south-west corner of the central business district. In early 1836 this settlement consisted of ‘about a dozen wattle and daub or turf huts, and the same number of tents’, plus Fawkner’s six-roomed hotel ‘of a very primitive order’ and Batman’s ‘mansion’ – a hut twenty feet by twelve that boasted a brick chimney.

The settlement grew rapidly. In 1837 Governor Bourke named it Melbourne after the British prime minister of the time, and appointed Robert Hoddle to make the first land survey. Hoddle laid out the new town in a rectangular grid on the north bank of the Yarra, largely surrounded by parklands through which stately boulevards – Royal Parade, Victoria Parade and St Kilda Road – led away from the town centre.

The first land sales were held in June 1837, with one hundred lots being sold at an average price of £38 per lot. More land sales followed over the next two years, with prices rising sharply. The population continued to grow rapidly, and a land-buying frenzy soon became Melbourne’s first speculative bubble. In September 1839, squatter Charles Ebden sold three lots for £10,224, having bought them for £136 two years earlier. Ebden sauntered into the Melbourne Club and announced, ‘I fear I am becoming disgustingly rich.’3 Melbourne’s first building boom followed, with the primitive wattle and daub huts being replaced by more substantial buildings of stone, brick or weatherboard.

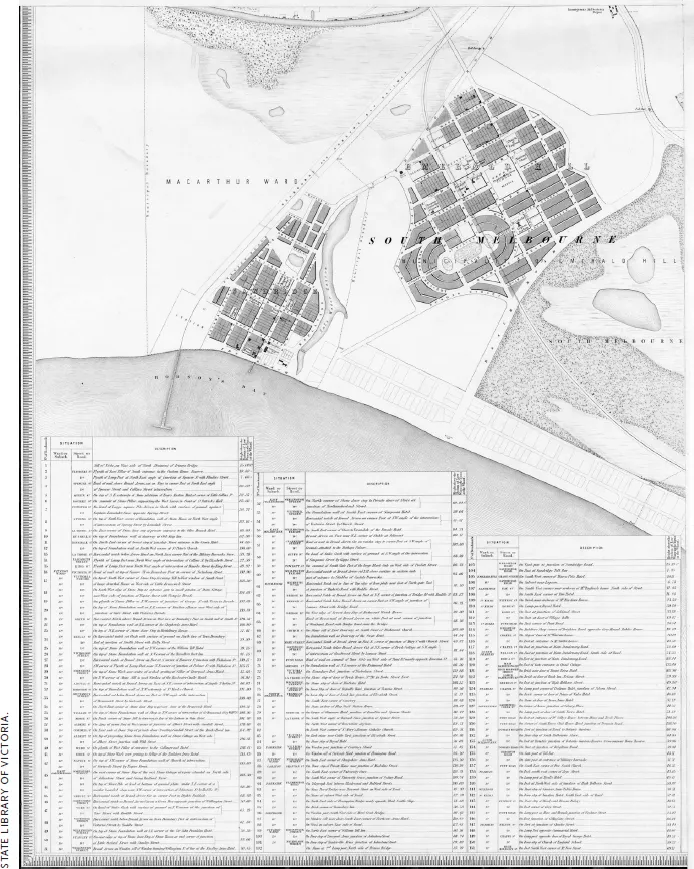

Map of Melbourne in the late 1830s showing Robert Hoddle’s street layout.

Every boom is followed by a bust. A downturn in the British economy in the early 1840s led to a fall in the price of wool, insolvencies among many undercapitalised Victorian squatters and economic distress in Melbourne. Land prices collapsed and with them the building boom. It was not until 1845 that rapid growth resumed. Once the recovery was underway, progress was again swift. Melbourne was incorporated as a municipality in 1842, and by 1851, when Victoria was separated from New South Wales, the population of Melbourne had reached 23,000. In 1848, the Port Phillip Gazette wrote, ‘Gaze in whatever quarter you choose, you are sure to discover a multiplicity of buildings rapidly raising their heads – many of them on an extensive and elegant scale.’4

The earliest developments beyond the original city grid were to the north and east, with settlement spreading to Fitzroy, Carlton, North Melbourne and Richmond in the late 1840s. The first suburbs in the south-east were St Kilda and Brighton; South Melbourne and Port Melbourne were much slower to grow – they were seen as swampy and unhealthy, and were subject to frequent flooding. In the early 1840s most of these suburbs were wastelands, with large areas leased as a stock run. The only exception was the area of higher ground named Emerald Hill. In the 1840s, the hill was described as ‘close in a rich sward, green as the freshest shamrock; no houses in sight except those of the then small Melbourne; trees scattered about and the whole eminence encircled by shining lagoons’.5 In 1851 a 10-acre reserve on Emerald Hill was set aside for the Melbourne Orphan Asylum, although building did not begin until 1855.

Victoria’s early development was driven entirely by the demand for wool from British industry and Melbourne grew as the commercial centre for a vast sheep run, with wool exports worth about £1 million in 1850. The discovery of gold in June 1851 rapidly changed the colony’s economic base. Exact figures are difficult to calculate, but Victoria’s gold production between 1851 and 1861 was more than 27 million ounces, worth over £100 million, a vast sum at the time.6 Victoria’s GDP had been little over £2 million in 1850; in 1860 it was more than £33 million – an annual growth rate that can rarely have been exceeded.7 Melbourne was transformed from a tiny and remote colonial settlement into the richest city in the world. The population soared from 23,000 in 1851 to 135,000 in 1861, far surpassing Sydney, and the city was transformed by a massive wave of building development. Great public buildings of the era included the Treasury Building, the State Library and Parliament House. A commercial building boom produced banks, offices, hotels and warehouses across the city. Melbourne’s suburbs rapidly grew to house the growing population, though regrettably Hoddle’s magnificent boulevards were not extended, leading to the bottlenecks in Sydney Road, Victoria Street and Bridge Road that continue today.

Treasury Building, Melbourne, 1877.

One of the first effects of the gold rush was the settlement of the wasteland south of the Yarra. News of the gold discoveries attracted tens of thousands of immigrants to Melbourne, and from early 1852 Hobson’s Bay was crowded with dozens of empty ships at anchor, their passengers having disembarked and their crews absconded. Melbourne lacked accommodation to house even a small percentage of the new arrivals, so thousands camped in primitive conditions in a canvas town that sprang up between Port Melbourne and the city. Much of Emerald Hill, as well as the land west of St Kilda Road, was covered with tents and a few crude timber buildings.

Early in 1852 Robert Hoddle laid out a street plan for Emerald Hill, and the first land sales were held in August of that year, with most lots bringing high prices. Further surveys and land sales followed, and by 1854 ‘a whole town of wooden houses [sprang] up like mushrooms; inns, shops and cottages’. So rapid was the growth of the new suburb that in May 1855 Emerald Hill became the first municipality to separate from the City of Melbourne, ahead of older suburbs such as Richmond and Fitzroy.8

Victoria’s gold rushes attracted young adventurers from all around the world, most keen to try their luck at the diggings, but others seeking their fortunes in the colony’s rapidly growing commercial world. Among them was William Parton Buckhurst, born in Rochester, Kent, in 1831. At the age of seventeen Buckhurst had sailed for America, where he worked for several years as a miller in Illinois and the Mississippi Valley before heading for California to try his luck on the goldfields. In later life he told dramatic tales of his adventures among the Pawnee and Sioux tribes. He claimed he had been offered a job in Salt Lake City by Mormon leader Brigham Young to run a flour mill, but told Young that ‘ten shillings a day was not enough to run two wives’ and continued his journey to California. He spent two years prospecting before settling in San Francisco, where he found himself in the middle of a violent and dangerous crisis when a large group of vigilantes challenged the rule of law, kidnapping a Supreme Court judge.9

South Melbourne (Emerald Hill), Melbourne and its suburbs, Map 3, 1855. Surveyor-General Victoria; compiled by James Kearney, draughtsman; engraved by David Tulloch and James D Brown.

Emerald Hill and Sandridge, South Melbourne, c1875.

While in San Francisco, Buckhurst made his first ventures into real estate development, buying and selling several houses, but in 1857 he decided to move on and try his luck in Victoria. After a few months prospecting on the Dargo, Wentworth and Nicholson rivers ‘with moderate success’, he came to Melbourne and obtained work in the Swanston Street real estate office of Mr HG Nelson. While with Nelson, Buckhurst used his savings to buy twelve properties in Napier and Moray Streets in South Melbourne, valued in the rate books at between £31 and £42. The properties had three- or four-room cottages made of wood, lath and plaster or brick, and were rented out to working-class families, providing Buckhurst with a modest income. At the government land sales in August 1859 he paid £146 for a quarteracre block, on which he built two modest cottages to rent.10 His early commitment to the South Melbourne area was also demonstrated when he stood for the Emerald Hill Municipal Council in the elections of June 1859.11 Although he was not elected, he quickly became a prominent and active local figure.

In spite of his employment with Nelson and his successful developments, it appears that Buckhurst took some time before committing himself to a career as a real-estate agent and developer. When he gave evidence in 1860 against a Mr Thomas Jones, who had burgled his home in Emerald Hill, Buckhurst gave his occupation as ‘miller’.12 Early in 1861, however, he opened his own real estate agency in Clarendon Street, Emerald Hill and did not look back. In later life he said that ‘The rent of his first premises was 30 shillings, and his profits for the first week were 3s. 6d! The second week he made 16 shillings, the third week he made £2 2s., and had thus 12 shillings to the good, after having paid his rent.’13 On 1 May 1861 Buckhurst married Anne Faram, the daughter of George Faram, a leading South Melbourne contractor. Over the following decade they had eight children.

Buckhurst was an astute and entrepreneurial estate agent, who quickly built up a solid and profitable portfolio. His choice of South Melbourne as the base of his business proved shrewd, as the suburb was growing rapidly. The population more than doubled between 1861 and the end of the decade, growing from over 8000 to nearly 17,000, and the island of settlement on Emerald Hill was still surrounded by large areas of empty land ripe for development once the swampy areas were drained.

As with most early Melbourne suburbs, South Melbourne in the 1860s and 1870s was socially diverse, with pockets of dire poverty only a few blocks away from the mansions of the wealthy. It was not until after the land boom and bust of the 1880s and 1890s that Melbourne began to see divisions along lines of social class, with Richmond, Collingwood, Carlton and South Melbourne becoming almost exclusively working-class suburbs, while the wealthy moved to Toorak, Hawthorn, Kew and Brighton.

In the late 1860s Buckhurst regularly advertised his business in the Record, the local Emerald Hill newspaper: ‘Auctioneer, Estate Agent & Valuer, 116 Clarendon St. ...