![]()

Explore Jerusalem

The Jaffa Gate and the Armenian Quarter

The Via Dolorosa and the Christian Quarter

The Muslim Quarter

The Jewish Quarter

Temple Mount

East Jerusalem

West Jerusalem

Outlying areas

![]()

The Jaffa Gate and the Armenian Quarter

With seven entrance gates and four distinct quarters, deciding where to begin a tour of the Old City can be tricky. The Jaffa Gate is as good a starting point as any. This is the main western entrance to the Old City and the most convenient starting point for the Ramparts Walk, a stroll around Jerusalem’s sixteenth-century walls, the very best way to make your first acquaintance with the Old City.

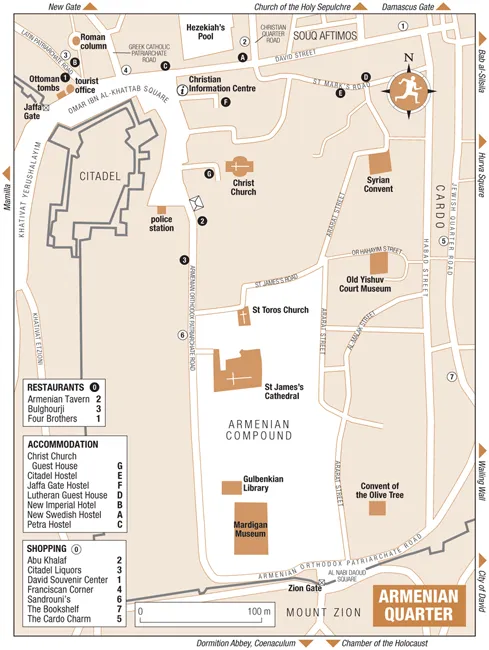

The Jaffa Gate opens up into the busy Omar Ibn al-Khattab Square full of cafés and souvenir sellers. Running east from here, David Street splits the Armenian Quarter to the south from the Christian Quarter to the north. Smaller and quieter than the Old City’s other three quarters, the Armenian Quarter is a city in miniature, home to a dwindling two-thousand-member community which maintains a separate language, alphabet and culture. Its attractions include the imposing Citadel (also known as the Tower of David), one of the city’s most interesting sights – a historical and strategic stronghold where you can explore archeological remains dating back through the ages, and then come back in the evening to enjoy a state-of-the-art sound and light show. The heart of the quarter is St James’s Cathedral, one of Jerusalem’s loveliest churches, whose services follow the beautiful Armenian liturgy. Also here is the world’s very first Christian church, St Mark’s in the Syrian Convent, where mass is still celebrated in the ancient Syriac tongue. At the quarter’s southern end, the Zion Gate, pockmarked with bullet holes from the fighting in 1948, provides access to neighbouring Mount Zion.

The Jaffa Gate and the Armenian Quarter |

The Jaffa Gate

The turreted Jaffa Gate (Sha’ar Yafo in Hebrew, Bab al-Khalil in Arabic) is one of the most imposing in Jerusalem and dates from the early sixteenth century. As with so many places in the city, the gate’s names reflect the differing viewpoints of its varied population: the English and Hebrew names both refer to the ancient port of Jaffa on the Mediterranean coast, embarkation point for immigrants, pilgrims and early tourists, while the Arabic comes from the holy town of Hebron (Al-Khalil; see "Hebron"). Cars can enter the Old City here, thanks to the touring kaiser, Wilhelm II. The story goes that, when he made his visit in 1898, the Ottoman authorities, mindful of a legend that every conqueror of the city will enter through the gate, had a breach made in the wall between the gate and the Citadel so that the kaiser and his entourage would enter through that instead. The gate itself is on the north side of the breach. When he took Jerusalem for the British in 1917, General Edmund Allenby famously refused to enter through the kaiser’s breach and insisted on dismounting, along with his entourage, and entering on foot through the gate itself as a mark of respect to the city.

If you’re coming from West Jerusalem, you’ll approach along the southern end of the Jaffa Road, which passes alongside the city wall. A concrete plaza now bridges the road, connecting the Jaffa Gate to the new Mamilla development.

The Jaffa Gate and the Armenian Quarter | The Jaffa Gate |

Omar Ibn al-Khattab Square

Once through the L-shaped gateway, Omar Ibn al-Khattab Square meets you with a tourist office (see "Tourist information"), shops, cafés, hostels and hustlers all aimed at capturing the tourist trade. Just inside the gate, beside the tourist office, two trees in a small, fenced-off compound indicate the positions of two Ottoman tombs, belonging to the architects who designed the walls for Suleiman the Magnificent. The sultan had both of them executed, according to one story because they mistakenly left Mount Zion outside the walls, or, according to another tale, because Suleiman didn’t want them to build anything else which might surpass their walls. The right-hand grave still bears, in the Ottoman style, a stone turban at its head.

Just across Latin Patriarchate Road (in the Christian Quarter, strictly speaking), the New Imperial Hotel sits atop a covered arcade. In the middle of the arcade, a truncated Roman column dating from around 200 AD honours one Marcus Junius Maximus of the Tenth Legion, who may have been the governor of Judea at the time. The building containing the New Imperial Hotel, along with the neighbouring one housing the Petra Hostel, became the centre of a controversy in 2005 when it emerged that Jewish investors had bought the land they stand on in a secret deal with the Greek Orthodox Church. Palestinian members of the church were outraged given the sensitive location of the land. In response, an extraordinary Pan-Orthodox Synod was convened in Istanbul, which not only deposed the Greek Patriarch, Irineos I, but also had his name struck off all the official lists; the Israelis were furious, and initially refused to recognize or deal with the new patriarch Theophilos III.

Across the square, opposite the Citadel, the Christ Church was built in 1842 under the supervision of the first Anglican bishop of Jerusalem, Michael Solomon Alexander, a rabbi who converted to Christianity. The cool, airy interior reflects this Jewish influence, with a wooden screen inscribed with the Lord’s Prayer in Hebrew as a centrepiece.

Straight ahead from the gate, the main Tariq Suweiqet Alloun, now called David Street (Khutt Da’ud) runs east through the main market area into the heart of the Old City, separating the Armenian and Christian quarters (to the right and left respectively). The route is often used by Israelis and Israeli-led tour groups en route to the main sights. To the right of the square, Armenian Orthodox Patriarchate Road leads into the heart of the Armenian Quarter.

Hidden away behind the buildings on the north side of David Street, and inaccessible to the public – though you can see it from the roof of the Petra Hostel – Hezekiah’s Pool was originally a reservoir which used to be fed by aqueducts from the Mamilla Pool, and is indeed thought to date from the reign of Judah’s King Hezekiah (715–687 BC). A nineteenth-century travel guidebook notes that the pool’s water was generally used only for washing purposes, but that poor people sometimes resorted to drinking it, with the result that many of them became seriously ill. Today the pool is empty, and used as a rubbish tip, but plans are afoot to do it up and open it as a public space.

The Jaffa Gate and the Armenian Quarter | The Jaffa Gate | Omar Ibn al-Khattab Square |

Suleiman the Magnificent and the walls of Jerusalem

In days of old, a city needed walls to defend it from attack and to allow rulers to use it as a military base. When the Roman Emperor Hadrian had the Jewish city of Jerusalem razed in 135 AD and founded Aelia Capitolina in its place, he didn’t endow it with walls, possibly fearing that it might be used as a stronghold by rebels, but walls were eventually added, probably when the Tenth Legion left in 289 AD, and they followed roughly the course of today’s city ramparts. The Roman walls were augmented or altered over the centuries (Caliph Al-Zahir had them rebuilt in the mid-eleventh century after a series of earthquakes had severely damaged them), but essentially they remained in place until 1218, when the Ayyubid sultan Al-Mu’azzam, fearful that the city might be taken and used as a base by the Crusaders, had them pulled down, with only the Citadel left standing. This rendered Jerusalem defenceless, effectively transforming it from a city into little more than a large village. So it remained until 1536, when the Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent had a dream in which the Prophet Mohammed appeared and told him to see to the city’s defence. Suleiman immediately put his finest architects on the case, and in 1541 the walls were completed, looking pretty much as they are today, Jerusalem’s greatest architectural legacy from the Ottoman period.

The Jaffa Gate and the Armenian Quarter | The Jaffa Gate |

The Ramparts Walk

The Jaffa Gate is the best place to begin the Ramparts Walk (Sat–Thurs 9am–4pm, Fri & eve of holidays 9am–2pm; 16NIS, student 8NIS) around the walls of the Old City. Built between 1537 and 1540 AD, the ramparts were commissioned by the Ottoman sultan (see "Suleiman the Magnificent and the walls of Jerusalem"). They run for 4km and you can walk along two sections: the northern section between the Jaffa Gate and the Lions’ Gate, and the southern section between the Citadel and the Dung Gate. The section of the wall alongside Temple Mount is not accessible to the public.

Although you can exit from the walk at any of the seven gates (an eighth – the Golden Gate on the eastern wall of Temple Mount – is closed until the appearance, or Second Coming, of the Messiah), you can enter only from the Jaffa Gate, where there is an entrance at the northern side of the gate (by Stern’s jeweller’s) for the northern section, and one at the moat by the Citadel on the southern side for the southern section, or the Damascus Gate (the entrance is inside the Roman Plaza below the gateway, see "The Roman excavations").

You can buy tickets for the Ramparts Walk (16NIS) at any of the three entrance points; alternatively, you can purchase a combined ticket (55NIS valid three days) which includes one visit to the Jerusalem Archaeological Park, the Roman Plaza at Damascus Gate (see "The Roman excavations"), and Zedekiah’s Cave (King Solomon’s Quarries) just to the east of Damascus Gate (see "The downtown area and Nablus Road"). Note that although the Ramparts are open on Saturdays, you cannot buy tickets then – they can be bought in advance; in theory they can be bought online at www.pami.co.il, but the site is in Hebrew only.

The Jaffa Gate and the Armenian Quarter |

The Citadel (Tower of David)

Carefully excavated, with all the periods of its development clearly marked, the imposing Citadel next to the Jaffa Gate, commonly (but incorrectly) known as the Tower of David (April–Nov Sat–Thurs 10am–5pm, Fri 10am–2pm; Nov–March Sun–Thurs 10am–4pm, Fri 10am–2pm; 30NIS; combined museum entry with sound and light show ticket 65NIS; free guided tours in English Sun–Fri 11am; www.towerofdavid.org.il) is well worth taking time to explore. The site will take a good couple of hours to see properly.

The steep outer walls of the Citadel Surrounded by a dry moat, the Citadel occupies a strategic position on the western hill of the Old City fortified by every ruler of Jerusalem since the second century BC, when it was at the city’s northwestern corner and highest point. Herod strengthened the old Hasmonean walls by adding three new towers, and the historian Josephus tells us there was an adjoining palace “baffling all description”, remains of which have been excavated in the Armenian garden to the south. This palace were the Jerusalem residence of the Roman Procurator (whose headquarters was in Caesarea) until the Romans burned it down during the Jewish Revolt of 66–70 AD. When the city was razed by the Romans in 70 AD, only one of Herod’s three towers – the Phasael, named after his brother – remained standing. During the Byzantine period the tower, and by extension the Citadel as a whole, acquired its alternative name, the Tower of David, after the Byzantines, mistakenly identifying the hill as Mount Zion, presumed it to be David’s Palace. The Citadel was gradually built up under Muslim and Crusader rule, acquiring the basis of its present shape in 1310 under the Mamluk sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad. Suleiman the Magnificent later constructed a square with a monumental gateway in the east. The minaret (no public access to the top), a prominent Jerusalem landmark, was added between 1635 and 1655, and took over the title of “Tower of David” in the nineteenth century, so that the term sometimes refers to the Citadel as a whole, and sometimes specifically to the minaret.

From the Phasael tower in the northeast corner of the Citadel, there are good views over the excavations inside and the Old City outside, as well as into the distance south and west. On the way up, a terrace overlooking the excavations has plaques identifying the different periods of all the remains you can see. These include part of the Hasmonean city wall, a Roman cistern, and the ramparts of the Ummayad Citadel which held out against the Crusaders in 1099.

The Jaffa Gate and the Armenian Quarter | The Citadel (Tower of David) |

The Jerusalem History Museum

The rooms around the “archeological garden” containing the excavations have been turned into a Museum of the History of Jerusalem, a fascinating exhibition illustrating the history of Jerusalem from Jebusite times until the present. For each period there is a model of the city as it was, culminating with a magnificent zinc model made by Hungarian artist Stefan Illes in 1872. Every half-hour, a beautifully animated film is shown in the Phasael Tower, summarizing the city’s history in fourteen minutes. There’s also a spectacular evening Sound and Light Show (in English Mon, Tues & Wed, April–Oct 8pm & 10pm, Nov–March 7pm & 9pm; 50NIS; combined ticket for the museum and the show 65NIS; running time 45min), billed as “the most sophisticated in the world” and featuring state-of-the-art special effects projected onto the walls of the Citadel. Themes include King David, of course, the city’s fall to the Babylonians and then the Romans, the rise of Christianity, Mohammed’s night journey to heaven, the Crusades, and the British Mandate. It ends with a prayer for peace in the city. If you’re going in winter, remember that it can get quite chilly sitting outdoors in the evening, so bring a sweater or jacket.

The Jaffa Gate and the Armenian Quarter | The Citadel (Tower of David) | The Jerusalem History Museum |

Jerusalem’s Armenian Community

There have been Armenians in Jerusalem since before the Byzantine period – immigrants from ancient Armenia (corresponding now to eastern Turkey, modern Armenia, Azerbijan and Georgia), which, in 301 AD, became the first state to accept Christianity as its religion. As early as 638 AD, Caliph Omar Ibn al-Khattab guaranteed the religious rights of Jerusalem’s Armenian community, a guarantee respected by subsequent Muslim rulers. Under Crusader rule too, the Armenians fared better than the other eastern churches due to links between the Crusader kingdoms and the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia. Armenia itself fell to the Mamluks in 1375, and later came under the rule of the Seljuks and Ottomans, who actively suppressed Armenian c...