- 1,050 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Emerald Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology

About this book

This book provides an in depth survey of the field of Industrial and Organizational Psychology (I/O), a specialized field within the larger discipline of psychology also called Work and Organizational Psychology, Occupational Psychology, and Organizational Psychology. I/O is the scientific study of how individuals and groups behave in the performance of work activities and in the context of organizations. It is also the application of this research to improving the effectiveness and the well-being of people and the organizations in which they work. It is part science, contributing to the general knowledge base of psychology, and part application, using that knowledge to solve real-world problems.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Emerald Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology by Robert L. Dipboye in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Organisational Behaviour. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

A History of I/O Psychology

Introduction

This chapter reviews the development of industrial and organizational (I/O) psychology from the first crude attempts at application in the late 1800s to the sophisticated profession that constitutes modern I/O psychology. Understanding how the field developed requires a consideration of the contexts in which I/O psychologists have conducted their activities at various points in time over the last 150 years. These contexts include the historical and societal events, management theory and practices, and the development of the larger discipline of psychology.

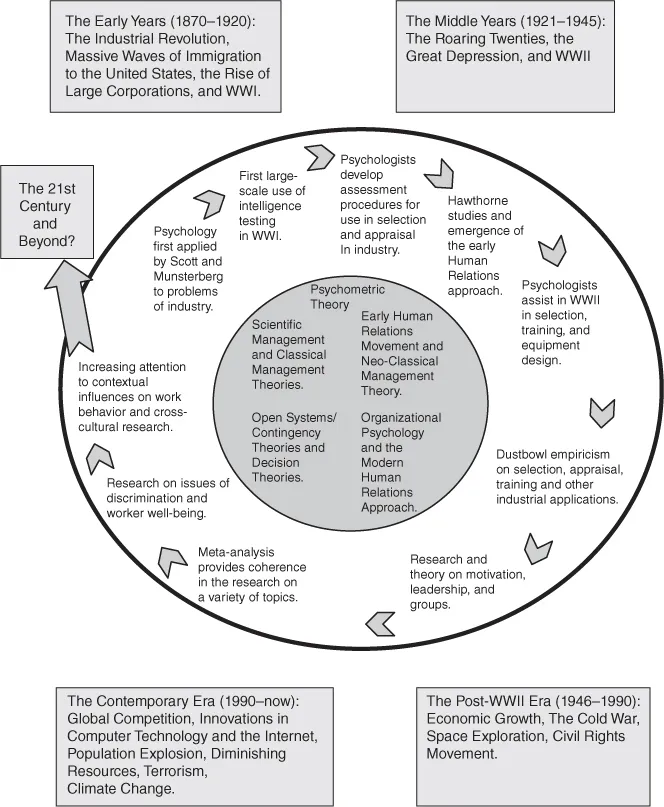

Fig. 1.1 summarizes this evolution of I/O. The boxes outside the circle anchor four periods (early, middle, post-WWII, modern) and the historical and societal events occurring during these years. The chapter begins with the early years from 1870 to 1920 defined by the industrial revolution and the rise of the corporation. This era ends with WWI, a very significant event in the development of I/O psychology. The end of WWI signals the beginning of the middle years. During these years, there was the economic boom of the 1920s followed by the economic bust of the Great Depression in the 1930s and yet another war, WWII. After the end of WWII came the postwar years in which the United States, the dominant economic and military power in the world, was engaged in a Cold War with the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China. This competition among the great powers spawned space exploration and unprecedented progress in science and technology. Also occurring during this period was the Civil Rights Movement, which had a huge impact on I/O psychology. Finally, the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union marked the beginning of the contemporary period. Global competition, the development of computer technology and the internet, terrorism, and climate change are some of the societal forces that are ongoing and characterize this period, which continues to the present time.

Over these four periods, psychology evolved and I/O emerged as one of its subdisciplines. The outer edge of the circle represents the development of I/O. Some of the major efforts of I/O psychologists to meet the needs associated with historical and societal events at the time punctuate this period. For instance, with the outbreak of WWI psychologists developed the first paper-and-pencil tests of cognitive ability to allow screening of prospective soldiers. The inner circle summarizes influential theories in psychology and management that were associated with what was happening in the field of I/O and the world at large. This timeline provides a context for the development of I/O psychology, but do not interpret this as a rigid chronology. For instance, the classical theories of management were dominant during the early years and less so today. Yet, this approach to thinking about management of people in organizations did not suddenly end with the middle years. Indeed, Classical Theory and Scientific Management still influence thinking about how to manage people in organizations.

Fig. 1.1. The Evolution of Industrial and Organizational Psychology in the Context of Historical Events and Theory.

Note: The dominant theoretical orientations are in the inner circle. Some of the major contributions at each period in history are in the outer circle.

Note: The dominant theoretical orientations are in the inner circle. Some of the major contributions at each period in history are in the outer circle.

Still another caveat to consider when reviewing this chronology of events in I/O psychology is its U. S.-centric perspective. This admitted bias is because researchers and practitioners from the United States overwhelmingly dominated I/O psychology in the early and middle years. This has changed dramatically over the last two to three decades. I/O psychology is today a multi-national and cross-cultural discipline. There are active I/O societies on all the continents and the number of articles authored by those outside the United States and published in the major I/O journals is increasing at a rapid rate. However, because the focus of this chapter is on the past rather than the future of I/O, the developments occurring in the United States are the primary focus. For a more detailed account of the development of I/O psychology in the United States and around the world, you should read A History of Industrial and Organizational Psychology (Bryan & Vinchur, 2012) and Historical Perspectives in Industrial and Organizational Psychology (Koppes, 2007).

The Early Years (1880–1920)

Prior to 1880, owners of business managed the people who worked for them. They gave little thought to how to hire, train, motivate, or evaluate their employees. No systematic theories existed to guide the management of people at work, the organization of tasks, or the structuring of reporting relationships in organizations. There were no business schools as we know them today. Psychology was part of philosophy and did not exist as an empirical science. All this changed in the late 1800s. Owners no longer managed but instead hired people who specialized in planning, organizing, staffing, coordinating, and controlling employees to facilitate the accomplishment of the objectives of the organization. Psychology emerged as a separate discipline during this period and from the beginning, psychologists were applying what they had learned about human behavior to problems of management. I/O psychology became the subdiscipline that took the lead in these early applications.

What Were the Major Forces Shaping Work during the Early Years?

Industrial and Organizational Psychology emerged at the time of the transition of the U. S. economy from an agrarian society to an industrial society. Mass production, the rise of the corporation, consumerism, and massive immigration to the United States marked these early years.

Industrialization and Mass Production

The Industrial Revolution began in the late 1700s with technological innovations such as the cotton gin and steam engine (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrial_Revolution). It continued through the 1800s and early 1900s with the invention of the telephone, the sewing machine, the automobile, the incandescent light bulb, the diesel engine, the airplane, the Bessemer process and open hearth in steel making, and the spread of the telegraph. Unlike the European nations where railroad systems connected existing cities, the rapidly growing network of railroads was responsible for creating cities in the United States.

Although the invention of new machines was a driving force of the industrial revolution, innovations in the management of people were as important as advances in hard technology. A crucial development in management was the idea that employers should divide the work that employees perform into narrow, specialized tasks. This was not “discovered” in the 1800s. Division of labor had appeared in times past, but what were unique were the refinement, systematization, and formalization of the principle. One of the earliest applications was by Josiah Wedgwood who revolutionized the manufacture of pottery in the 1700s (McKendrick, 1961). The old methods of pottery making were becoming obsolete in meeting consumer demand:

The family craftsman stage had already given way to the master potter with his journeymen and apprentices recruited from outside the family, and this in turn was becoming inadequate to deal with the growing complexity of potting production. (McKendrick, 1961, p. 31)

Wedgwood introduced one of the first examples of the assembly line:

His designs aimed at a conveyor belt progress through the works: the kiln room succeeded the painting room, the account room the kiln room, and the ware room the account room, so that there was a smooth progression from the ware being painted, to being fired, to being entered into the books, to being stored. Yet each process remained quite separate. (McKendrick, 1961, p. 32)

Rather performing all the tasks that constituted this assembly line, each worker specialized in one specific task:

His workmen were not allowed to wander at will from one task to another as the workmen did in the pre-Wedgwood potteries. They were trained to one particular task and they had to stick to it. (McKendrick, 1961, p. 32)

In addition to division of labor, Wedgwood advocated piece rate incentives, the organization of supervision in the hierarchical layers, and the use of rules to discipline workers. In his famous economic treatise Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith (1776) attributed much of the prosperity achieved in the industrialized nations to the application of these principles.

The division of labor, the assembly line, and other management innovations introduced by Wedgwood and others were notable but were not widespread. It was not until the late 1800s and early 1900s that these techniques emerged as dominant methods of organizing and managing work. The most publicized and famous of the applications of the assembly line was in 1913 when Henry Ford introduced a moving assembly line procedure at his Highland Park, New Jersey plant in the United States.1

According to numerous books and articles, the assembly line was the primary cause of the increases in productivity and decreases in costs that occurred in manufacturing during the first few decades of the 1900s. Reductions in the cost of goods enabled the working and lower socioeconomic classes to purchase all sorts of goods and fueled an economic boom. A bundle of innovative management practices that included incentives, rules, and supervisory approaches accompanied the introduction of the assembly line at the Ford plants (Williams, Haslam, Williams, Adcroft, & Johal, 1993; Wilson & Mckinlay, 2010). Part of the bundle of changes introduced by Ford was an increase in wages for workers who worked on his lines. In 1914, he decided to double the wages of his assembly line workers to $5.00 a day, a remarkable increase in wages for that time. He also reduced the workday to an 8-hour day from the 10–12 hours per day that was more typical in the early 1900s. The increased wages and reduced working hours attracted huge numbers of workers to his plants and along with the assembly line procedures allowed the mass production of vehicles. The increased wages also created customers for these automobiles. The business community severely criticized these innovations, but after seeing the positive impact on productivity, they were soon imitating Ford’s increase in wages and reduced working hours.2

Massive Waves of Immigration

Factories in the booming cities of the United States needed workers. The demand for labor led to a huge wave of immigration of Europeans to the United States (27.5 million immigrants between 1865 and 1918, 89% from Europe) and a movement of farmworkers within the United States to the cities to work in the mills. Throughout the world, but especially in the United States, technological innovation transformed what had been a predominately rural and agricultural existence into societies dominated by large cities and manufacturing.

Rise of the Corporation

As important as technological innovation, the assembly line, and urbanization was the rise of the large corporation. Prior to the industrial revolution, the dominant work organization was a small entrepreneurial firm in which the owners were the managers. A new organizational entity emerged to deal more efficiently with the larger scale of operation that characterized industry in the mid- to late 1800s. The owners were shareholders with little contact with the firm, and they hired managers to run the firm and serve as agents of the shareholders. This new form of organization is the corporation. The corporation as a legal entity was controversial when it first emerged 150 years ago and remains controversial. For an interesting documentary on the emergence of the corporation and the continuing controversies, you may wish to check out the documentary The Corporation on YouTube.3

A highly significant event occurring in the United States in 1886 was the Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad Supreme Court decision that gave corporations the same rights and protections given to people under the U. S. Constitution.4 This included the right of management to use the corporation’s wealth to influence the government. This case set the precedent for the U. S. Supreme Court’s recent decision in Citizens United in which attempts to reform campaign finance were declared to be a violation of the constitutional right of free speech.5 During the latter part of the 1800s, governments did not regulate business practices, and corporations could take ruthless actions to eliminate their competition and create monopolies. They could also crush attempts to form unions by firing, harassing, or even physically threatening workers who tried to organize. The period in the United States that followed the end of the Civil War in 1865 and continued until the early 1900s was the era of the “robber barons” such as Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and Jay Gould. These men amassed enormous wealth by destroying their competitors, subjugating their employees, and ignoring public interests.

Rise of Consumerism

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, American industry was enjoying the combined benefits of a host of positive business conditions. These included technological innovations such as mass production, seemingly unlimited natural resources, cheap labor immigrating from Europe, strong government support, expanding markets, and a social climate that lionized material success. All the ingredients for rapid growth and prosperity were in place. The great American experiment was working! Evolving business organizations, like the country itself, saw themselves as virtually invulnerable to outside forces. If a firm, or an individual for that matter, did not succeed, only it (or he/she) was to blame. Initiative and growth could overcome virtually any obstacle that might arise. With natural resources, cheap labor available, and virtually no restrictions on corporations, the United States became the economic, industrial, and agricultural leader of the world. The rise of the large urban area and manufacturing brought pollution, poverty, crime, disease, and large economic inequalities, but also dramatically improved the economic status of the industrial worker. The average annual income of nonfarm workers improved dramatically with t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Chapter 1. A History of I/O Psychology

- Chapter 2. Research Methods in I/O Psychology

- Chapter 3. Work Motivation

- Chapter 4. Work-Related Attitudes in Organizations

- Chapter 5. Occupational Stress

- Chapter 6. Social Processes in Organizations

- Chapter 7. Social Structures in Organizations

- Chapter 8. Groups and Teams in Organizations

- Chapter 9. Leader Emergence and Effectiveness in Organizations

- Chapter 10. Work Analysis

- Chapter 11. Criterion Development, Performance Appraisal, and Feedback

- Chapter 12. Employee Training and Development

- Chapter 13. Principles of Employee Selection

- Chapter 14. Constructs and Methods in Employee Selection

- Chapter 15. Epilogue

- Appendix: What is I/O Psychology?

- References

- Index