- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Stakeholders, Governance and Responsibility

About this book

While it is generally accepted that both governance and corporate social responsibility are concerned with the way that an organisation manages its relations with its stakeholders, the actual relationships are not simple. The stakeholders who are considered to be dominant and most powerful can change dramatically over time. This is particularly so when governance or CSR is considered in the context of non-commercial forms of organisation. This book re-examines these relationships and the way in which they are changing and developing. The various contributions to the book address different aspects of these relationships from a wide international and interdisciplinary perspective.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Stakeholders, Governance and Responsibility by Shahla Seifi,David Crowther in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

STAKEHOLDERS’ ROLES IN

ORGANISATIONS

VALUE CREATION FROM STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIPS BETWEEN COMPANIES AND NGOS

ABSTRACT

Recent years have witnessed a change in the corporate social responsibility (CSR) debate from questioning whether to make substantial commitments to CSR, to questions of how such a commitment should be made. Given that CSR initiatives increasingly are carried out in collaboration with non-governmental organizations (NGOs), business–NGO (Bus–NGO) partnerships are becoming an increasingly important instrument in driving forward the sustainable development agenda. The aim of this chapter is to explore motivations to partner, the value-added of Bus–NGO partnerships as well as what is enabling and impeding the realization of this value.

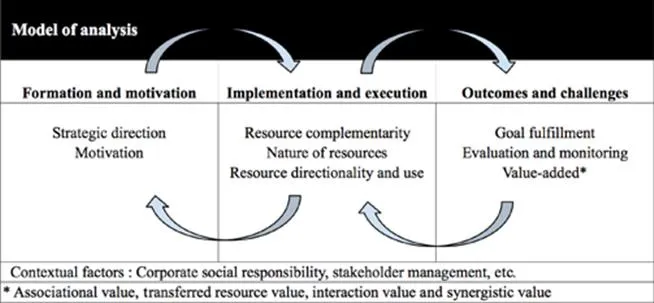

An analytical model is developed based on contributions from partnership literature (Austin, 2000, 2007; Austin & Seitanidi, 2012a, 2012b; Seitanidi & Ryan, 2007) and the resourced-based view. This has resulted in a process model with the following three phases: (1) formation and motivation; (2) implementation and execution; and (3) outcomes and challenges.

The empirical part of the chapter focuses on three specific partnerships in Kenya. Kenya is one of the most prosperous and politically stable states in Africa, with high growth rates making it an attractive launch pad for businesses to enter partnerships with NGOs.

The partnerships studied were all pilots still flirting with this new form of collaboration modality and struggling themselves to clearly define the value-added. Partnerships are still experimental efforts involving a steep learning curve, and showing signs that they have to evolve further as well as innovate in order to produce the expected benefits. All three partners referred to learning as one of the most important intangibles.

Business and NGOs had both different and overlapping motivations that made them propel into cross-sector alliances. The partnerships have to be configured to satisfy a variety of different motivations, resulting in complex stakeholder management. For the NGOs, it is about designing new development models, due to an instrumental need of resource enhancement and idealistic need to deliver more sustainable and efficient solutions. The analysis shows clear signs of NGOs beginning to realize the importance of classical business skills, such as management, marketing, and technical systems that companies can provide. Looking at the business, the partnership fit right into the wider strategic sustainability “umbrella” of the corporation, notably the employees are central stakeholders. It is argued that a business’s approach to CSR and perception of its own responsibilities need to evolve to higher levels according to Austin’s Collaboration Continuum to produce valuable synergies in a partnership with an NGO (Austin, 2000).

Finally, the analysis shows a Bandwagon effect throughout the sectors, where the reason to form a partnership is because everybody else is doing it, and both NGOs and businesses do not want to miss out on potential benefits.

Keywords: CSR; sustainability; capabilities; collaboration; learning; value-added

INTRODUCTION

Since the 1990s, cross-sector social partnerships aimed at promoting socially, environmentally and economically responsible forms of business have emerged (Bitzer & Glasbergen, 2010). The imperative for collaboration can be derived from probably irreversible changes being generated by powerful political, economic, and social forces (Austin, 2000). Additionally, awareness has grown on the complexity of the world’s sustainability and development problems, increasingly asking for joint approaches. No longer can society look to the governments as the main problem-solver, and the limits of the state have been acknowledged putting an end to the era of the ever-bigger national government (Austin, 2000).

Nonprofit organizations have proliferated to address social and environmental problems, but face serious challenges due to a reduction in government support as well as changes in traditional philanthropy. Constrained by a diminishment in resources and limited institutional capacities, nonprofit organizations are encouraged to generate revenues with commercial activities by collaborating closer with the private sector (Selsky & Parker, 2005), and despite numerous concerns, partnerships are now viewed as a necessary tactic (Selsky & Parker, 2005).

The private sector today also faces increasing expectations to provide evidence of corporate social responsibility (CSR) to their customers and stakeholders (Austin & Seitanidi, 2012a, 2012b). Businesses are therefore increasingly re-examining their traditional philanthropic practices and seeking new strategies of engagement with their communities (Austin, 2000). However, the more corporations have begun to embrace CSR, the more they have been blamed for society failures (Porter & Kramer, 2011). Engaging in cross-sector partnerships is therefore a way to attempt the third-party endorsement needed for businesses in order to be viewed as good and responsible citizens (Austin, 2000).

Such a changed environment has implications for the way businesses and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) think and work. While both scholars and practitioners have paid much attention to nonprofit-business partnerships and proclaimed it to be the next big wave to hit large both corporations and NGOs, few organizations have yet succeeded in implementing it (Olsen & Boxenbaum, 2009). This chapter investigates the growing interdependence of the sectors, which continuously develop new rules of collaboration, and provide a deeper understanding of, notably, the added value of cross-sector partnerships. The research questions to be addressed are: What motivates businesses and NGOs to spend time and valuable resources working together? And which factors enable and impede the realization of the value-added in Bus–NGO partnerships?

THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

The partnership and CSR literature is still an emerging area of research and, due to the multidisciplinary subject matter, poses serious challenges to theory. There is no singular theory dealing with all aspects of Bus–NGO partnerships. When studying Bus–NGO partnerships, several underlying mainstream theories are often applied such as stakeholder theory, resource dependency, social network theory, transaction cost theory, and the resource-based view of the firm. Although developed within the management area, it is argued that they can be applied to other kinds of organizations, such as NGOs, as well.

Austin (2000) has extensively researched cross-sector partnerships. He puts forward the paradox: “differences are what make cross-sector social partnerships work and valuable, but also what makes them extremely challenging.” The literature on Bus–NGO partnerships has extensively documented some of these challenges, but remains a relatively young research field and is mostly concerned with the business case for engaging in partnerships (Neergaard, Janni, & Crone, 2009). Here research on Bus–NGO partnerships has been driven primarily by resource dependency and transaction cost theories where value tends to be defined economically and from the perspective of a focal firm (Koschmann, Kuhn, & Pfarrer, 2012; Phumpiu & Gustafsson, 2009). However, critics are emerging on the feasibility to study Bus–NGO partnerships by focusing on individual organizations. It is instead proposed to consider these partnerships as distinct organizational forms, beyond the sum total of their individual members, as the level of analysis (Koschmann et al., 2012). A consideration that is also supported by Seitanidi, seeing cross-sector partnerships as evolving new forms of organizing institutions that touch upon a number of social issues (Seitanedi & Crane, 2009).

Due to their dynamic character and versatile forms, Austin (2000) characterizes the degree and form of interaction between NGOs and business as the Collaboration Continuum (CC). The underlying logic of his theory is a conceptual shift in the nature of profit/nonprofit relations (Seitanidi & Ryan, 2007). He terms four stages through which a relationship may pass: the philanthropic stage (traditional philanthropy); the transactional stage (sponsorship and cause-related marketing); integrative stage (partnerships); and, finally, the transformational stage (shared value).

According to Austin & Seitanidi, 2012a, 2012b, what is central to effective collaboration is value creation, and he therefore advocates that academics and practitioners deepen the understanding of the collaborative value creation process. A basic theoretical premise, which has been confirmed in practice to some extent, is that new value can be created by combining each organization’s distinctive resources and capabilities. What has not been giving great attention is how the magnitude of the value created is related to the nature and use of the resources deployed within the partnership context (Austin & Seitanidi, 2012a, 2012b).

Austin and Seitanidi, (2012a, 2012b) have therefore developed a conceptual framework named the Collaboration Value Construct (CVC) to enable the analytics of the co-creation of value in Bus–NGO partnerships. They define collaborative value as: “the transitory and enduring benefits relative to the costs that are generated due to the interaction of the collaborators and that accrue to organizations, individuals, and society” (Austin & Seitanidi, 2012a, 2012b).

Austin and Seitanidi argue that the CVC provides a more refined set of reference terms and concepts with which to examine how NGOs and businesses come together to create value. Where the CVC involves both the micro, meso, and macro levels, and involves four interrelated components through which one can analyze the co-creation process, we will consider the value generation process through the window of which Austin and Seitanidi term the Value Creation Spectrum. The Value Creation Spectrum posits four sources of value and identifies four types of collaborative value that suggest different ways in which benefits arise (Austin & Seitanidi, 2012a, 2012b). The four sources of value are: resource nature; resource complementarity; resource directionality; and linked interests; and the four types of values are: associational value; transferred resource value; interaction value; and synergistic value.

Value creation in partnerships is depending on the combination of the distinctive resources and capabilities from business and NGOs. The resourced-based view (RBV) argues that sustained competitive advantage derives from the resources and capabilities firm controls that are valuable, rare, imperfectly imitable, and nonsubstitutable (Barney, Wright, & Ketchen, 2001), as well as having the organization in place that can absorb and apply them. These resources and capabilities can be viewed as bundles of both tangible and intangible assets (Barney et al., 2001), and when these resources and their related activity systems have complementarities, their potential to create sustained competitive advantage is enhanced (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000). RBV is a value addition to the analysis expanding the work of Austin.

The following analytical framework has been developed based on the theoretical foundation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Analytical Framework.

PHASE ONE: FORMATION AND MOTIVATION

How a partnership originates reveals much about the subsequent processes and outcomes of the partnership. As an example, it can reveal much about the power relations that will emerge among participants (Miraftab, 2004). Who initiated the process and sought partnership with the other sectors is significant. So is the way in which one partner may fill a need of another (Miraftab, 2004). Presumably, corporate motives to engage stakeholders will influence the character and outcome of the partnership. Examining the partners’ motivations can reveal linked interests by providing an early indication of partners’ intentions and expected benefits (Seitanidi, Koufopoulos, & Palmer, 2010). Seitanidi et al. (2010) suggest that the formation stage of partnerships reveals much about their dynamics and their potential to deliver organizational and social change. The formation stage will also be used to discuss the degree of which the collaborating organizations can achieve congruence in their respective perceptions, interests, and strategic direction (Austin & Seitanidi, 2012b). In the first phase, focus will be centered on the following factors: motivations and strategic direction.

PHASE TWO: IMPLEMENTATION AND EXECUTION

The focus in second phase is how Bus–NGO partnerships are executed and implemented. It is argued that implementing the partnership is the value creation engine of cross-sector interactions where the value creation process can be either planned or emergent. It is important to investigate the specific sources of value, with a focus on strategic argumentation, resources, and capabilities.

Looking at the Nature of resources, partner organizations can contribute to the collaboration either with generic resources or they can mobilize and leverage core valuable organization-specific resources (Austin & Seitanidi, 2012a, 2012b). F...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Part I Stakeholders’ Roles in Organisations

- Part II Industry and Stakeholders

- Index