![]()

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION – ROBERT CLARK

In September 2010, I started out on one of the most enjoyable journeys I have ever undertaken. It was not to some strange, far off and exotic land but a return to somewhere I had not been to since my teenage years – a return to the world of academia. Two years later I graduated from Buckinghamshire New University with a Master of Science degree in Business Continuity, Security and Emergency Management. Attaining a master’s degree was the fulfilment of a promise made many years before not only to myself but to my mother Vera as well. I am very grateful that, at the age of 94 years, she was there with me to witness my graduation.

Unlike many who embark upon a master’s degree I had no first degree, although I justified my place on the course by the commercial business continuity experience I had gained throughout my career. Naturally, I did not make this journey alone and found myself studying in a cohort of six mature students that quickly bonded not just academically but socially too. We came from different backgrounds bringing with us our own experiences of the real world and we quickly learned to draw on each other’s strengths. Our university head of department, Phil Wood, once remarked that he always learned something from our group discussions, such was the diversity of knowledge that we collectively brought to the table.

Although we did not appreciate it at the time, we started preparing the content of this book towards the end of 2010. It was then that work commenced on the business continuity case studies which subsequently became the basis for this book.

These studies are diverse and cover many of the mainstream threats that business continuity practitioners are called upon to address. Some are based upon our personal experiences while others cover multiple threat scenarios. One such example is the 2005 Buncefield oil depot disaster, and the study even considers the question of whether it was caused by a cyber attack.

Each study looks at the events that occurred, interprets and analyses the facts while reaching appropriate conclusions and recommendations. Where similarities existed between the original case studies, they have been combined and, where appropriate, extracts from our dissertations have also been included. One such example is ‘A Tale of Three Cities’ which is a comparison of the terrorist attacks on Madrid (2004), London (2005) and Glasgow Airport (2007). Here the common theme is not just terrorism but the targeting of the respective transport infrastructures of the three cities.

In business continuity, we can all be guilty of thinking only of major incidents that could have a detrimental effect on our organisations. To that end, a chapter has been included which focuses on a series of smaller incidents, each of which still had the potential to have big impacts on organisations.

Amongst the studies is a contribution from Catherine Feeney, senior lecturer in Tourism, Hospitality and Events Management at Manchester Metropolitan University. Although she was not a member of the cohort, Catherine was invited to submit a chapter that focuses on the pandemic threat with specific emphasis on the impact that the 2003 SARS outbreak had on the tourism industry.

With the graduation now long since over and with a master’s degree in the bag, that tiny cohort is spread across the world in several different countries. But it is good to know that our academic efforts may also be of practical use to anyone who has an interest in, or is actively involved with, business continuity, information security or risk management. It is my hope that through this book and the experiences of those that it chronicles, more and more people will come to realise the importance of business continuity.

In 1974, I first became involved in business continuity management (BCM). In those days it was simply called disaster recovery and was solely about protecting an organisation’s information technology assets and electronic data. The mainframe dominated the computer world. The Internet was in its infancy and the threat from cyberspace was something you were more likely to read about in a science fiction novel than in the pages of a serious computing journal. It was to be almost another ten years before the personal computer was to arrive on the scene and over 20 before the commercialisation of the World Wide Web. Even the formation of the Business Continuity Institute did not happen until 1994. In fact, business continuity management and the Internet are about the same age.

My first involvement with BCM was as a computer operator with IBM and I was based in a computer room, or data centre if you prefer, which was about the size of a soccer pitch. Located at Havant in the UK, ten IBM System 360 mainframe computers and all their respective peripheral units filled that room. Among those mainframes were the computers designated to process all of IBM World Trade's customer orders and manufacturing logistics transactions. That included anything that was ordered by a client outside of the USA along with all the associated manufacturing instructions. It should come as no surprise that this operation was considered mission critical by IBM.

To ensure the continuity of this mission critical operation, two or three times a year a full disaster recovery test would be performed. This necessitated undertaking what we referred to as a ‘disaster fall-back test’ and involved transferring the operation to an IBM location in Germany or the Netherlands. Testing would occur over a weekend to minimise any disruption to the host location and, allowing for travel time, would be done and dusted over a four day period.

By the mid-1980s IBM recognised that the ‘IT environment’ represented only part of the story and other aspects of its business, such as its staff, properties and even supply chain were also crucial. This started to be reflected in the various scenarios that were tested and rehearsed.

With so many businesses detrimentally affected, culminating in around 600,000 job loses, the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001 were a major factor in emphasising the importance of BCM globally. This was further accentuated by the subsequent launching of BS 25999 in 2006 which was adopted as the established BCM standard across many parts of the globe. Finally, after evolving for around 40 years, 2012 saw BCM finally come of age when it joined the ranks of the international standards, taking its place alongside the likes of quality management and risk management. The Business Continuity Management System, or ISO22301 as it is known, was up and running.

Through my consultancy work, I still find myself amazed at the degree of naivety that exists in both public and private sectors and the excuses offered for not embracing business continuity, which have long since lost any originality. Recently, I became aware of the German division of a multinational company finding itself under pressure from its corporate headquarters to implement business continuity management. Not sure how to go about this, they approached their Dutch colleagues and asked if they could have copy of their plan so they could adapt it. In fairness, they had had no BCM training and had no in-house expertise that they could draw upon. Even so, they could not understand that, while they were prepared to share their plans, the Dutch said ‘of course the plans won’t work in Germany’.

Even though the products and services that both the Dutch and Germans offered were very similar, their respective business impact analysis and threat assessment exercises generated very different results. This ultimately affected what BCM strategies they each needed to adopt and how their subsequent business continuity plans (BCPs) shaped up. Or to put it another way, for business continuity one size does not fit all! Furthermore, even the most comprehensive of BCPs are effectively useless unless they are thoroughly tested and maintained.

But do you know what threats your organisation is facing and which of those could present a risk to its survival? If you have not performed a threat analysis exercise as part of your business continuity arrangements, the answer is most probably no. In fact, do you know how long your organisation has to recover from a serious incident (e.g. a fire, flood, IT failure, supply chain failure, product recall, loss of expertise, etc.) before its very survival could be placed in serious jeopardy? Is it several months, a few weeks, maybe two or three days or perhaps just a couple of hours? Five of the companies featured in this book ceased trading after catastrophes that they were unprepared for. Most went with barely a whimper although one collapsed in the most spectacular fashion. A sixth company narrowly survived a catastrophe because of what can best be described as an ‘Act of God’.

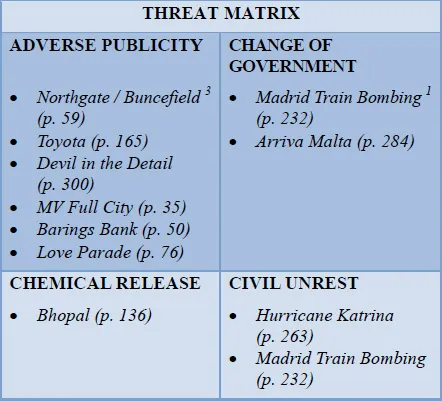

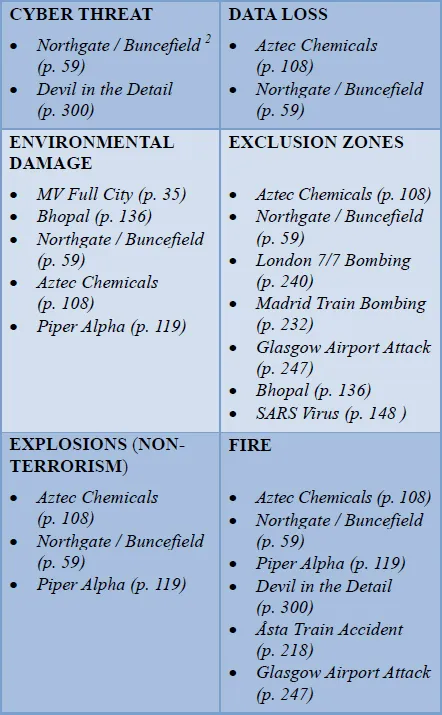

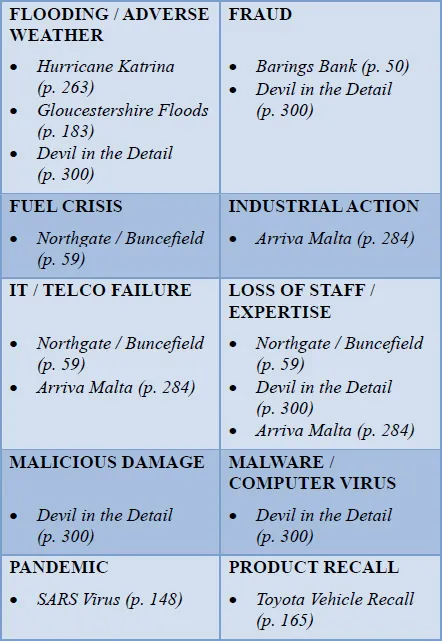

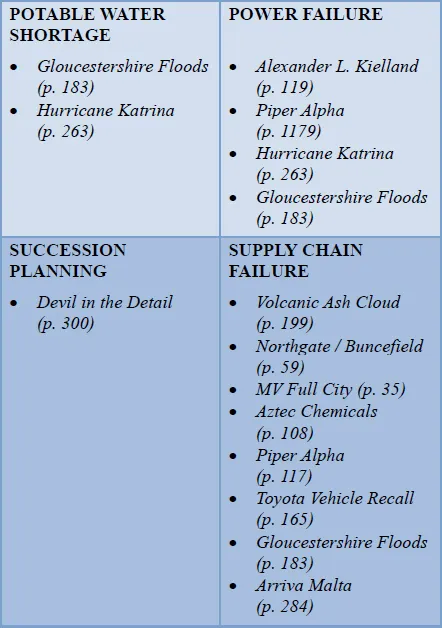

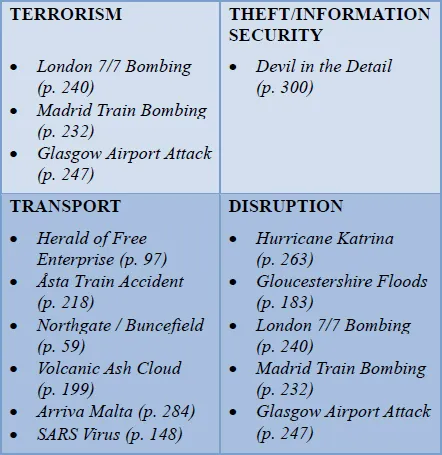

The threat matrix that follows in Figure 1 includes 27 threats which are relatively common and would not look out of place in the results of a BCI member survey. They all appear in at least one of the case studies in this book; most appear several times. Around half of the incidents resulted in physical injuries and fatalities. Trauma was also not uncommon. Yet only one chapter, A Tale of Three Cities (p. 227), devotes its attention to terrorism which helps illustrate that the workplace can be a very dangerous place.

Figure 1: Occurrence of threats within case studies

Notes

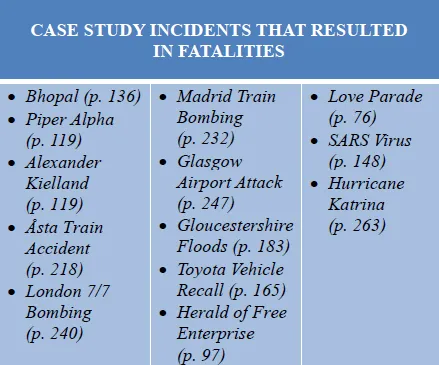

Figure 2 below indicates which of the case study incidents resulted in fatalities.

Figure 2: Case study incidents that resulted in fatalities

![]()

CHAPTER 2: THE MV ‘FULL CITY’ INCIDENT – NORWAY’S WORST EVER OIL SPILL – JON SIGURD JACOBSEN

The MV Full City was a Panama registered bulk carrier with a gross tonnage of 15,873 tonnes. It was capable of taking a cargo weighing around 11,000 tonnes creating a deadweight tonnage of 26,758 tonnes. Built at Hakodate, Japan, it was completed in 1995, Chinese crewed and Chinese owned by the Roc Maritime Inc. It has twice made headline news. In 2011, it was attacked by Somali pirates in the Arabian Sea although it was swiftly rescued by a combined United States, Turkish and Indian naval force.

This case study, however, examines the earlier headline news event involving the same ship when it ran aground some two years previously, leaking its fuel oil in the process. It considers whether the incident was preventable, what the environmental impact for the surrounding area was, as well as the local response capability a...