![]()

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION TO AGILE

Overview

Before we consider Agile governance and audit we need a common understanding of the history of Agile and how it is defined. The dictionary definition of Agile is ‘nimble, mentally quick or acute’. The thesaurus adds words such as active, lively, prompt, quick, sharp and sprightly. These are not words usually associated with IT programmes and projects!

Many organisations have their own terminology and definitions – of varying accuracy and validity. This also causes some confusion, so throughout this book I rely upon the following widely accepted structures:

- Agile definition

- Agile Manifesto

- Agile principles

- Agile 3 pillars of control.

An understanding of these will enable the auditor to discuss the key issues, risks and controls for a project with the Agile project team in a practical and clear way. In this chapter we will look at the history of Agile before considering each of the preceding structures, and also look at some of the main types of Agile project.

Agile’s history

The Agile approach did not start in the world of software and IT. Agile’s origins are in engineering with the manufacturing practices that emerged in the Far East. Consumers have constant changes in needs and purchasing patterns and so businesses needed to adapt quickly to new product demands. We have also seen a rapid change in technology available to customers and manufacturers. The product development lifecycles available to suppliers were too long. All the work in developing a product or service could be quickly lost if a competitor came to market with a similar offering sooner. On the production side too there was increasing demand for Just-in-Time production, to reduce supply chain costs and the risk that components would be delivered for finished goods that would not be produced due to better versions being available.

For example, consider the rapid development changes of audio recording over the last 30 years. Various media have come and gone. Look at the length of time vinyl recordings were in use – and how quickly they have been replaced by tape, 8 tracks, cassettes, CDs and MP3, all in quick succession.

Or consider the retail high street and the competition it faces from online selling. The rapid growth of digital photography has seen the demise of shops offering photographic development. We are now seeing the next stage as digital cameras give way to mobile phones and tablets as ways of not only capturing images but also of transmitting them to social networks or storing them in the Cloud. Further changes are inevitable. We live in fast-changing times, which require fast and flexible change processes.

This also applies to software. Only 30 years ago, if I wanted to communicate with colleagues I would write a memo, send it to a typing pool, redraft and then send. This would take 2–3 days with a similar time lag for my colleagues to respond. Now I just send an email and expect an instant response. During the dot-com boom it was no good taking 2–3 years to develop systems – competitors would get there a lot quicker. Like me you may have friends and relatives who had brilliant ideas for new web offerings only to lose out because they did not implement and market them fast enough. Someone else got there first!

The same principles apply in IT and software. There are numerous examples where MS-DOS-based projects for providing desktop systems were abandoned overnight when Windows or MAC GUIs were introduced. Large projects that were set to deliver major changes for the organisation concerned often failed because they just took too long in development. Many tried to accommodate the changes in requirements, but this proved expensive and time consuming. There were too many runaway projects; I know of examples costing three or more times the original estimate by the time they were abandoned – with little or nothing to show by way of business benefits. Many of the runaway projects I have reviewed also failed due to lack of business input into requirements, particularly from senior stakeholders. A new approach was required and so the concepts of Agile project development were adapted to the world of systems and software. This started during the dot-com boom but has now extended to other types of projects including ERP implementations, maintenance and DevOps projects, and the Cloud and big data projects.

Agile definition

So what actually is Agile? Many organisations claim to be following an Agile approach and using Agile tools in different ways. You could be forgiven for thinking that the Agile structure lacks organisation and discipline and so is completely alien to the way that you normally work or audit projects. There are a number of definitions, standards and guidelines that can be used to provide consistency. The definition I favour, which is also widely accepted, is shown below:

Agile Defined

A-gil-i-ty (ə-'ji-lə-tē) Property consisting of quickness, lightness, and ease of movement; To be very nimble

- The ability to create and respond to change in order to profit in a turbulent global business environment.

- The ability to quickly reprioritize use of resources when requirements, technology, and knowledge shift.

- A very fast response to sudden market changes and emerging threats by intensive customer interaction.

- Use of evolutionary, incremental, and iterative delivery to converge on an optimal customer solution.

- Maximizing BUSINESS VALUE with right sized, just-enough, and just-in-time processes and documentation.1

This definition sees change during a project as inevitable, and almost welcomed. Instead of resisting or continuing to deliver as originally planned it stresses the need for flexibility and adaptability in the provision of useful deliverables. It does this by breaking the project up into smaller deliverables and ensuring full interaction from the business (the customer) in agreeing what is to be delivered and when. Users welcome this approach because they can ‘touch and feel’ real products and benefits rather than trying to interpret often complex and jargon ridden documentation.

The definition is widely recognised and can be a useful aid to auditors interacting with Agile project teams.

Critics of traditional, non-Agile project approaches often refer to:

- too much planning – emphasis on the inputs rather than the outputs.

- too little communication, particularly between business and project teams – relying on formal documentation rather than actually talking and listening to one another.

- lack of engagement, accountability, involvement and commitment of business sponsors.

- too much delivery in one go.

Agile tries to overcome these issues by breaking the project up into smaller deliverables.

Agile Manifesto

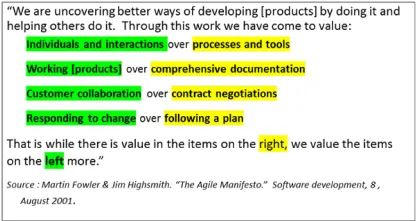

On a cold February day in 2001 a group of Agile experts met in a ski resort in the Wasatch mountains of Utah. Between skiing and après-ski they discussed the common elements of Agile and produced the Agile Manifesto. This was seen as a way of uniting thinking on the key elements for all the different approaches (e.g., Scrum, Extreme Programming (XP), Unified Process (UP) etc.). There are now a very large number of signatories to the Manifesto, and the list is still growing. The Manifesto is widely accepted as a basis for Agile (see Agilemanifesto.org).

The Agile Manifesto (see overleaf) is very useful when auditing Agile projects. It helps to emphasise the differences between Agile and other approaches.

Culturally in my experience auditors are inclined to the right-hand side of the list (process, documentation etc.) and developers to the left (individuals and product etc.). Indeed the characteristics on both sides could be seen as best practice regardless of what approach is used – the only difference is the extent of their significance to the project approach. We will look at this in more detail in the next chapter to improve the understanding between the two groups. But first let’s consider the Manifesto in more detail.

1. People or methodologies?

There is no single methodology to ensure 100 percent success on any single project. Project processes and tools are useful to enable monitoring and reporting. Other tools can provide efficiency gains in the performance of routine tasks (e.g., sharing documents across the team or recording test results). However, projects never fail just because the wrong approach or tools were used; tools are only as good as the people using them. The skills, experience, knowledge and maturity of project teams will have a more fundamental impact on whether or not a project meets its objectives. Effective project teams ensure there is strong communication and understanding between them. Agile focuses more on the individuals and how they interact, both within the team and with stakeholders, than the tools and methodologies used.

I am often asked about the compatibility of Agile and some of the standard project methodologies such as PRINCE2. In my experience, it depends on how rigidly these approaches are being applied. If the principles are being followed in a general way then they can be compatible. However, if the organisation has strict requirements for adhering to these approaches, there are likely to be conflicts with Agile. There are a number of strong opinions either way on this topic, and the Internet contains many interesting papers on it.

2. Comprehensive documentation or a deliverable that helps the business?

To some auditors this sounds like heresy. How can a project really be successful without ‘comprehensive documentation’? As an auditor myself I have often reported on the lack of documentation for projects. Let’s face it, drafting documentation is far less interesting for a developer than writing new code or demonstrating the clever features they have created to a customer. As a result the quality of documentation is often poor. In practice, the documentation is not really understood by the intended audience and can often be misinterpreted. Even where it is good, documentation is rarely maintained, or even used effectively beyond the life of the project development.

Some documentation is still important, however, particularly to support major decisions made during a project, to provide work instructions to users or configuration information to assist with the future maintenance of the system. However, much documentation prepared during projects is just surplus paper. Detailed specifications and user requirements that are not properly written or read and are just filed for reference provide little or no benefit to the customer. They are more interested in receiving a product they can use to meet their business requirements, which includes basic documentation to enable them to effectively use the features available. Let me illustrate – you go to buy a new car and the showroom quotes two prices: