![]()

1 MINK SLIDE

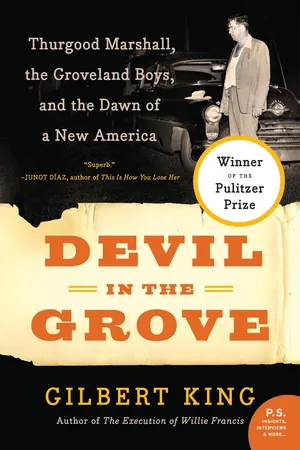

Interior of the Morton Funeral Home, Columbia, Tennessee, showing vandalism of the race riots in February 1946. (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Visual Materials from the NAACP Records)

November 18, 1946

IF THAT SON of a bitch contradicts me again, I’m going to wrap a chair around his goddamned head.”

One acquittal after another had left Tennessee district attorney general Paul F. Bumpus shaking his head in frustration over the NAACP lawyers, and now Thurgood Marshall was hoping to free the last of the twenty-five blacks accused of rioting and attempted murder of police in Columbia, Tennessee. The sun had been down for hours, and the start of a cool, dark night had settled over the poolrooms, barbershops, and soda fountains on East Eighth Street in the area known as the Bottom, the rickety, black side of Columbia, where, nine months earlier, the terror had begun. Just blocks away, on the news that a verdict had been reached, the lawyers were settling back into their chairs, fretfully waiting for the twelve white men on the jury to return to the Maury County courtroom. They’d been deliberating for little more than an hour, but the lead counsel for the defense, Thurgood Marshall, looked over his shoulder and knew immediately that something wasn’t right. Throughout the proceedings of the Columbia Race Riot trials, the “spit-spangled” courtrooms had been packed with tobacco-chewing Tennesseans who had come to see justice meted out. But the overall-clad spectators were equally intrigued by Marshall and his fellow NAACP lawyers: by the strange sight of “those niggers up there wearing coats and talking back to the judge just like they were white men.”

Marshall was struck by the eeriness of the quiet, nearly deserted courtroom. The prosecution’s table had been aflutter with the activity of lawyers and assistants throughout the trial, but none of them had returned for the verdict. Only the smooth-talking Bumpus had come back. All summer long he’d carried himself with the confidence that his Negro lawyer opponents were no match for him intellectually. But by relentlessly attacking the state’s case in a cool, methodical manner, Marshall and his associates had worn Bumpus down, and had already won acquittals for twenty-three of the black men on trial. The verdicts were stunning, and because the national press had defined the riots as “the first major racial confrontation following World War II,” Bumpus was no longer facing the prospect of humiliation just in his home county. The nation was watching and he had begun to unravel in the courtroom, becoming more frustrated, sarcastic, and mean-spirited as the trial progressed.

“Lose your head, lose your case,” was the phrase Marshall’s mentor, Charles Hamilton Houston, had drilled into him in law school. Marshall could tell that his adversary, seated alone at the prosecutor’s table, was in the foulest of moods as he was forced to contemplate the political ramifications of the unthinkable: his failure to win a single conviction against black lawyers defending black men accused of the attempted murder of white police in Maury County, Tennessee.

The shock from the summer’s not-guilty verdicts had worn off by November, and Marshall sensed that the white people of Columbia were becoming angrier and more resentful of the fact that this Northern Negro was still in town, making a mockery of the Tennessee courts. He’d watched patiently as Bumpus stacked the deck in his own favor by excusing every potential black jury member in the Maury County pool (there were just three) through peremptory challenges that did not require him to show cause for dismissal. And Marshall had paid close attention to the desperation in Bumpus’s closing statement to the jury, when the prosecutor warned them that if they did not convict, “law enforcement would break down and wives of jurymen would die at the hands of Negro assassins.” None of it surprised Marshall. He was used to, and even welcomed, such tactics from his opponents because they often helped to establish solid grounds for appeals. But Marshall also noticed that the atmosphere around the Columbia courthouse was growing more volatile.

A political cartoonist for the Pittsburgh Courier now doing public relations work for the NAACP had been poking around the courthouse and had come to believe that the telephone wires were tapped and that the defense lawyers were in danger. Learning this, Marshall refused to discuss any case details or sleeping arrangements over the phones, and the PR representative reported back to Walter White, the executive secretary of the NAACP, that “the situation in the Columbia Court House is so grave that anything may happen at any time.” White issued a memorandum to NAACP attorneys, demanding “no telephone calls be put through to Columbia or even to Nashville [where Marshall was staying] unless and until Thurgood says that it is safe to do so.” White noted that “we are dealing with a very desperate crowd” and want nothing to “jeopardize the lives of anyone, particularly persons as close and as important to us as Thurgood and his three associates.” White even contacted the U.S. attorney general’s office and warned that if anything happened to Marshall while he was in Tennessee, it would “create a nation-wide situation of no mean proportions.”

Marshall’s associates didn’t need Walter White to warn them of any danger they might be in. They were local Tennessee lawyers who had investigated enough lynchings in these parts to know that the death threats they received from the citizens of Columbia were to be taken seriously. Sitting to one side of Marshall at the table was a forty-seven-year-old poker-playing highbrow with a faint Caribbean accent named Zephaniah Alexander Looby, who came to Tennessee by way of the British West Indies. At fourteen years of age and living in Dominica, Looby found work as a cabin boy aboard a whaling ship, and two years later, in 1914, “broke and bedraggled,” he jumped ship in New Bedford, Massachusetts, with the dream of becoming a lawyer. He eventually received his degree from Columbia Law School in New York and taught economics at Fisk University in Nashville until the call of civil rights law beckoned and Marshall put him on the Columbia case.

To Marshall’s left was the lone white attorney on the case, the young, hotheaded Maurice Weaver, who reveled in the danger of standing up to white authority and racism; on more than one occasion throughout the Columbia Race Riot trials he had nearly come to blows with prosecutors. Marshall and Looby enjoyed having Weaver around, in part because the two black attorneys were inherently polite and gracious in court whereas Weaver was something of a lightning rod for white anger. Whenever prosecutors or witnesses referred to a black as “that nigger,” Weaver loudly interrupted with objections, insisting that the person be referred to as “Mr. or Mrs.” for the record. Bumpus seethed.

Weaver also endeared himself to Marshall because the Tennessee lawyer liked to drink, though at one point during the trial, his provocative nature had become not only distracting but dangerous, and Marshall was forced to intervene. Weaver’s teenage and very pregnant wife, Virginia, decided that she’d like to see her husband at work and asked to ride along with Looby’s associates and black reporters. Locals were speechless when the pregnant white girl hopped out of a car packed with Negroes and marched straight into court. Marshall, observing the commotion, pulled her aside and told her to take a Greyhound bus to court next time. “You almost started another lynching here in the courthouse,” he warned.

As the jury of twelve began filing back into the courtroom, Looby and Weaver searched their tired, sullen faces for a hint of the verdict. Marshall was on edge; he remembered how colleagues and friends had urged him not to return to Columbia. Over that “terrible summer of 1946,” he’d been running a constant fever while working in courtrooms that had no bathrooms or drinking fountains for blacks. The long hours, relentless travel, and Tennessee heat were taking their toll, but Marshall would not slow down. By July the lawyer’s body had finally wilted. Mid-case, he succumbed to exhaustion and a debilitating pneumonic virus that led to a long stint in a Harlem hospital, followed by weeks of doctor-ordered bed rest. Still, from his bed, and against everyone’s wishes, Marshall continued to lead late-night telephone strategy sessions with Looby and Weaver until he could no longer stay away—and no one was going to stop him from boarding a train to Nashville. “The Columbia case,” he said, “is too important to mess up. And I, for one . . . am determined that it will not be messed up.”

MARSHALL WAS IN New York on February 26, 1946, when a desperate call from Tennessee came into the NAACP offices, describing a full-blown race riot in Columbia. An emergency meeting was called and Marshall learned that the trouble began the previous morning when a black woman, Mrs. Gladys Stephenson, went into a Columbia appliance store with her nineteen-year-old son, James, to complain about being overcharged for shoddy repairs to a radio. After loudly proclaiming that she’d take the radio elsewhere, Gladys exited the store with her son. But twenty-eight-year-old radio repair apprentice Billy Fleming did not appreciate the threatening look he got from James on the way out.

“What you stop back there for, boy, to get your teeth knocked out?” Fleming asked, before racing over and punching James in the back of the head.

James’s boyish looks were deceiving. A welterweight on the U.S. Navy boxing team, he barely flinched and countered with several punches to Fleming’s face, sending him crashing through a plate-glass window at the front of the store.

Bleeding profusely from his leg, the army vet came up fighting, and other whites joined the melee, shouting, “Kill the bastards! Kill every one of them!” One man went after Gladys, slapping and kicking her to the ground and blacking her eye. A few minutes later police arrived and carted mother and son off to jail. After pleading guilty to public fighting and agreeing to pay a fine of fifty dollars each, the two were about to be released when Billy Fleming’s father convinced officials to charge both Gladys and James with the attempted murder of his son; the two were held by police in separate cells. As the news spread that James Stephenson had gotten the better of Billy Fleming and sent him wounded to the hospital, Maury County became galvanized. A mob began to gather around town and outside the jail, and by late afternoon the sheriff was hearing talk that a group of men were planning to spring the “Stephenson niggers out of the jail and hang them.”

Carloads of young, white workers from the phosphate and hosiery mills in nearby Culleoka (where the Flemings lived) began arriving at the square, and more volatile World War II veterans joined them. Rumors that rope had been purchased had reached the Bottom, and Julius Blair, a seventy-six-year-old black patriarch and owner of Blair’s Drug Store, had heard enough. He’d seen firsthand what white mobs in Columbia were capable of in recent years, around that courthouse down the block. He’d been there when they’d taken one man out of jail and lynched him back in ’27, and more recently, there was young Cordie Cheek. The community was still raw over Cordie’s killing. The nineteen-year-old had been falsely accused of assaulting the twelve-year-old sister of a white boy he had been fighting with. The boy paid his sister a dollar to tell police that Cordie had tried to rape her, but a grand jury refused to indict and Cordie was released and abducted that same day by county officials, who took him to a cedar tree and hanged him. Julius Blair was well aware that it was Magistrate C. Hayes Denton’s car that had driven Cordie to his death; yet, undeterred, Blair marched into Denton’s office and demanded that Gladys and James Stephenson be released. “Let us have them, Squire,” Blair told him. “We are not going to have any more social lynchings in Maury County.”

Blair managed to convince the sheriff to release the Stephensons into his custody and arranged for them to be dropped off at his drugstore early that evening. By then, though, blacks in the Bottom had gone past being intimidated by the hooting and honking of armed whites circling the area in cars; they weren’t going to stand passively by this time while another Cordie Cheek lynching unfolded. More than a hundred men, many of them war veterans, took to the streets with guns of their own, determined to fight back at the first sight of a mob moving toward the Bottom. Armed and angry, they told the sheriff in no uncertain terms that they were ready if whites came down to the Bottom. “We fought for freedom overseas,” one told him, “and we’ll fight for it here.”

True to his word and hoping to avoid any more trouble, the sheriff released the Stephensons that evening, and Blair arranged for the two of them to be whisked out of town, “blankets over their heads” for their protection. “Uptown, they are getting together for something,” Blair told them.

The nearby white mobs meanwhile did not disperse, and blacks in the Bottom were growing more fearful as the night progressed. Drinking beer and circling in cars, whites fired randomly into “Mink Slide,” as they derisively referred to the Bottom. Blacks, drinking beer on rooftops, were also firing in response and by bad chance hit the cars of both a California tourist and a black undertaker. When half a dozen Columbia police eventually moved into Mink Slide, a crowd of whites followed behind. They were welcomed by shouts of “Here they come!” and “Halt!” and then, in the confusion, came a command, “Fire!” and shots were exploding from all directions. Four police were struck with buckshot before they retreated.

Reports of the skirmish roused whites around town. Columbia’s former fire chief headed toward Mink Slide with a half gallon of gasoline and the intent to “burn them out,” but he was shot in the leg by Negro snipers as he stole down an alley. With the arrival of state troopers and highway patrol reinforcements, the whites finally outnumbered the blacks and moved into Mink Slide, where they ransacked businesses until dawn, fired machine guns into stores, and rounded up everyone in sight. “You black sons of bitches,” one patrolman shouted, “you had your-alls’ way last night, but we are going to have ours this morning.”

Just after 6 a.m., gunfire from the street rained into Sol (son of Julius) Blair’s barbershop. “Rooster Bill” Pillow and “Papa” Lloyd Kennedy, hiding in the back, saw armed officers coming and were said to have fired a single shotgun blast before they were overpowered and taken into custody. They were stuffed with other blacks from the Bottom into overcrowded cells at the county jail and interrogated without counsel for days. Two prisoners were shot dead “trying to escape.”

Mary Morton had watched helplessly as state patrolmen barged into her family’s funeral home on East Eighth Street and arrested her husband. From the street she heard the sound of breaking glass and the building being ransacked. A short time later she saw the same officers, laughing and joking, return to the street. Once they were out of sight, Morton went inside...