- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

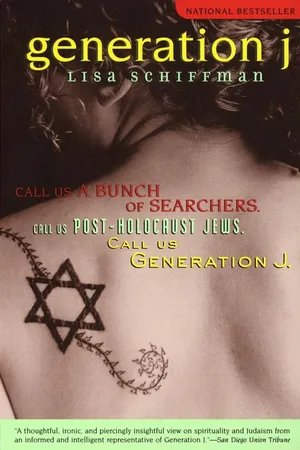

Generation J

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 5

Notes from the Field

SEPTEMBER 1

I never learned the how-tos of keeping ethnographic field notes. Grad-school courses offered no rules, no instructions about the process. I understood it was a science of intuition. You were simply supposed to figure it out yourself—write down what you heard, what you saw, and what you thought, in the hope that sooner or later you’d see patterns emerge. If you were patient, these patterns, invisible in life, would rise up through the blue-lined notebook paper, dot the page like small beams of light. The knots and gaps of a changing culture would be there, in your lap, illuminated.

I’ve decided to give it a go. Why not? For a month, I’ll keep field notes. The result will be a native’s ethnography, a small personal anthropology of Jewishness, the way it is now, for me, for people like me, those at once ambivalent and attached to something we haven’t quite figured out.

SEPTEMBER 2

I talk with Meryle Weinstein, a research associate at the Institute for Community and Religion. “The whole issue of what a Jew is,” she says, “is tenuous.”

Meryle feeds me the facts, according to the 1990 National Jewish Population Survey. I turn them into an index of sorts:

Estimated number of Jews in the United States: 8,190,000

Number of Jews that comprise the American “core Jewish population”: 5,515,000

Number of core Jews categorized as “Jews by religion”: 4,210,000

Number of core Jews categorized as “secular Jews”: 1,120,000

Number of Jews outside the core Jewish population: 2,676,000

Number of “Jews by choice,” a designation given to people born into another religion who now identify themselves as Jews—whether they’ve officially converted or not: 185,000

Percentage of Jews by choice who belong to a synagogue: 55.5

Percentage of Jews by religion who belong to a synagogue: 38.5

Percentage of secular Jews who belong to a synagogue: 5.6

SEPTEMBER 3

The numbers—what do they show? They show almost anything. They show that you can be a Jew if you call yourself a Jew. They show that some people are Jews because they go to synagogue, while others are Jews because they have Jewish blood. They show that lots of people of Jewish lineage don’t identify themselves as Jews. And they show that the Jewish Population Survey can give you a headache if you stare at it long enough.

The numbers—what do they mean? They mean that millions of American Jews fall outside mainstream Judaism. That’s the condition of my generation, the post-Holocaust generation of Jews. Millions answer the question of whether Judaism is religion, culture, or race with a shrug.

Religion. Culture. Race.

Synagogue. Museum. Body.

These are my vehicles to encounter Judaism, avenues at my disposal. Now for the test: Where will I truly make contact?

SEPTEMBER 4

I leave the Jewish Film Festival without getting crushed. Beforehand, I sit through a full-length movie about the Orthodox and a short about Jewish singles. Then two hundred Jews try to squeeze out the theater’s double doors with me. I flatten and make it through.

Outside the doors, a bearded guy in a too-small polyester suit and a knit skullcap flags me down, shoves at me a flyer for something called the Jewish Food Festival. A festival in celebration of Jewish, um, cuisine? I raise my eyebrows. I don’t even want to think of the ramifications.

“No thanks,” I say.

I take a few strides and he dogs my heels, waves his hands, tries to peer into my face. “Yes?” he yells, two feet from my ear. “You’ll come, yes? Latkes. Piroshki. Matzo brei. Saul’s chicken soup. Mamelah’s famous kishke. Next week. You take Highway 24 to the Broadway exit—”

I feel the heat of his breath. A voice rises within me. “Well,” it says, “are we feeling Jewish yet?”

SEPTEMBER 6

Santa Cruz. David and I spend hours in bookstores, then ride the Giant Dipper twice (me screaming on the downslide, envisioning the next day’s headlines: Earthquake Topples Beachside Roller Coaster, Kills All). We eat tostadas near the ocean, decide not to do anything as ambitious as swimming and instead fall asleep on the beach, legs entwined like curled limbs of driftwood.

Dinner at India Joze. We order tofu and taro root, soft things, entrees with made-up Indonesian names. Lots of peanut sauce. Then David opens his mouth, steps unknowingly into enemy territory.

“I’ve been thinking,” he says casually. “It’s actually kind of odd, the way your writing—the stuff you’ve shown me recently—keeps focusing on being Jewish.” He spears a tofu cube with his chopstick.

“What do you mean?” The back of my neck tenses.

“Well,” he continues. Munch. Spear. Munch. “You don’t go to temple.” Munch. Spear. “You don’t observe the Sabbath. You don’t even celebrate the major holidays. Remember—I was the one who wanted to go to the Passover seder last year. You bagged out at the last minute, so we didn’t go.”

The broccoli head. Fake to the left. Spear. “But your writing makes it sound as though Judaism is important, as though it’s a focus of yours in everyday life.”

“It is.” My hand closes in on my napkin, clenches the fabric.

“Really?” He looks at me.

“Yeah.”

He shrugs. “Whatever you say. I just don’t see it. I don’t see any evidence.”

“Evidence?”

“Right. You’re not religious. You don’t even belong to a Jewish cultural organization. You’re not a member anywhere. It’s like your Judaism is invisible.”

I lean forward over the table. I raise my voice. “The way I spend my days doesn’t express my thoughts. Going to temple wouldn’t make me more of a Jew. And the last time I checked, I didn’t need a membership card for this tribe. I was born into it.”

I’m pissed off. David looks baffled. “Wait. Look. I’m not trying to start a fight. I just want to understand your relationship to Judaism.”

I know he’s first rewinding and then fast-forwarding the conversation in his head, searching for clues, wondering, Where was the landmine? What did I say wrong?

But it wasn’t what he said. It’s what I thought I heard; it’s the thought behind his words; it’s what I projected—You aren’t a convincing Jew.

He’d hit a sore spot. I stab at my bits of Bo Lop beef. I wonder if he’s right.

Would going to temple be proof of a commitment to Judaism? I’d guess that many people in any given religious service spend time daydreaming. Some think about what they’re going to make for dinner or worry about their next paycheck. Some probably can’t explain why they go to services at all. Perhaps it’s a habit, like doing sit-ups in the morning. Perhaps it’s a form of solace, like sitting with old friends. But is it always evidence of religious commitment? Of a struggle for religious meaning? Of being a True Jew? No.

I say none of this. Dinner comes and goes. Half-eaten plates of noodles are exchanged for a check. I’m in a funk. In the silence of our drive back home, it occurs to me that my thoughts are rarely visible. Mostly they grow and change and shed as invisibly as layers of skin.

SEPTEMBER 8

I find this quote in The Book of Questions, by Edmond Jabès.

My brothers turned to me and said: “You are not Jewish. You do not go to the synagogue.”

I turned to my brothers and answered: “I carry the synagogue within me.”

SEPTEMBER 10

My parents will be in town for Rosh Hashanah. I decide to take them to a service. This could be a problem:

- I don’t belong to a temple.

- My mother has never been to a high holy day service.

- My father hasn’t gone since he was forced as a boy.

When my mother calls, I ask her if she’ll go.

“A service?” she says. “All of a sudden you want to observe Rosh Hashanah? Why?”

She pauses, asks suspiciously, “Are you going through some kind of religious Jewish phase?”

I get the phone number of Aquarian Minyan, the Jewish Renewal congregation in Berkeley. Jewish Renewal is a relatively new branch of Judaism. They claim a spiritual, politically aware, nonsexist, creative interpretation of Judaism.

The woman at the other end of the line tells me there are still spaces left for Rosh Hashanah services. She mentions that I should bring a drum if I have one. I reserve four seats even though I can already picture my mother’s raised eyebrows.

SEPTEMBER 13

The Claremont Hotel, room 202. My mother is wearing perfume. When I tell her that Aquarian Minyan’s flyer discourages wearing perfume at the service to protect the health of people with chemical sensitivities, she rolls her eyes.

“I can tell already what this night will be like,” she says. “Can’t we just go to a movie and forget about Rosh Hashanah?”

She grabs the flyer from me and reads aloud: “’Pillows will be provided for those who want to sit on the floor.’ Pillows? For the floor?”

She looks down at the tailored skirt and elegant jacket she’s wearing. Then she laughs. “Murray,” she yells to my father in the other room, “I think we’re going to be a bit overdressed for this one.”

David arrives at the hotel a half-hour late, gripping a cup of coffee. I see the coffee as a mild insult. Does he expect to fall asleep? We pile into the car. Everyone is too conscious that we’re going to a religious service. My father says something about the oppressive nature of organized religion. The car should have a placard attached—Warning: Three Uncomfortable Jews and a Lapsed Unitarian. Contents Under Pressure. My mother asks why Jewish services are going to be held at a Unitarian Church.

“Because the Jews own everything,” David says, “even the Unitarians.”

They banter until we stop at a light near the UC Berkeley campus. From a herd of students crossing the street emerge two Orthodox Jewish men. The men walk in front of us, a slow-motion detail of Jewish life. I see everything: their overgrown beards and black curls, their prayer-shawl fringes hanging beneath jackets, their dark-skinned hands grasping prayerbooks, their unabashed Jewishness. The juxtaposition is jarring. My family lacks a sense of necessity about the evening’s activity. It’s an elective, a novelty. Our voices cease as we stare. These men are a sign of some sort. They’re my conscience.

David breaks open the moment. “Ixnay on the ew-jay jokes,” he says, gangster-like, out of the side of his mouth. Who knows why, but I laugh. Then the light changes and we’re off.

The church is jammed. Most people are in loosely flowing cotton clothes. Luckily, no one is wearing beads. One guy, inevitably, is in tie-dye. I see a sign for a scent-free zone and steer my mother past it quickly. We find seats in front of a nice man resting his arm on a congo drum. He invites us to use it whenever we want. My parents are charmed.

Because this congregation has no rabbi, practiced laypeople lead the service. It begins with a request for all congregants to introduce themselves to those around them. David and I say hello to a few people and smile politely. Then I stare straight ahead until David nudges me.

“Look at your folks,” he says. “It’s like they’ve been coming here for years.”

I turn. They’re leaning forward, then backward, then to either side, talking at great length to everyone around them. Now they...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- One

- Two

- Three

- Four

- Five

- Six

- Seven

- Eight

- Nine

- Ten

- Eleven

- Twelve

- About the Author

- Praise

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Generation J by Lisa Schiffman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.