eBook - ePub

Hidden Figures Teaching Guide

Teaching Guide and Sample Chapter

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

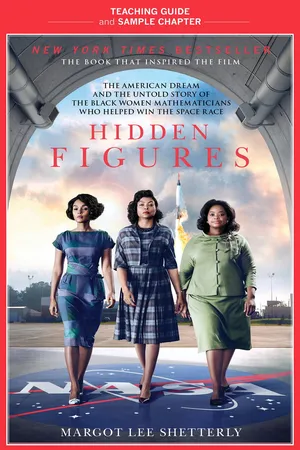

We know that teachers are always looking for new and inspiring books to assign to their students. To help you decide if Margot Lee Shetterly’s Hidden Figures is right for your classroom, we’ve created this special e-book that contains a teaching guide and sample chapters.

Hidden Figures has already been adopted as a common book on campuses across the country, and it has been assigned as required reading in high school and college courses on a variety of subjects—from history, math, and science to composition and women’s studies.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Sample Chapters from Hidden Figures

Copyright

Any Internet addresses, phone numbers, or company or product information printed in this book are offered as a resource and are not intended in any way to be or to imply an endorsement by HarperCollins, nor does HarperCollins vouch for the existence, content, or services of these sites, phone numbers, companies, or products beyond the life of this book.

Excerpts from HIDDEN FIGURES. Copyright 2016 by Margot Lee Shetterly.

Teaching Guide for HIDDEN FIGURES. Copyright 2017 by HarperCollins Publishers.

Teaching Guide for HIDDEN FIGURES. Copyright 2017 by HarperCollins Publishers.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

A hardcover edition of this book was published in 2016 by William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

FIRST WILLIAM MORROW MOVIE TIE-IN TRADE PAPERBACK EDITION PUBLISHED 2016.

Now a major motion picture from Twentieth Century Fox.

ISBN 978-0-06-236360-2

EPub Edition December 2016 ISBN 9780062363619

Version 08302018

Prologue

Mrs. Land worked as a computer out at Langley,” my father said, taking a right turn out of the parking lot of First Baptist Church in Hampton, Virginia.

My husband and I visited my parents just after Christmas in 2010, enjoying a few days away from our full-time life and work in Mexico. They squired us around town in their twenty-year-old green minivan, my father driving, my mother in the front passenger seat, Aran and I buckled in behind like siblings. My father, gregarious as always, offered a stream of commentary that shifted fluidly from updates on the friends and neighbors we’d bumped into around town to the weather forecast to elaborate discourses on the physics underlying his latest research as a sixty-six-year-old doctoral student at Hampton University. He enjoyed touring my Maine-born-and-raised husband through our neck of the woods and refreshing my connection with local life and history in the process.

During our time home, I spent afternoons with my mother catching matinees at the local cinema, while Aran tagged along with my father and his friends to Norfolk State University football games. We gorged on fried-fish sandwiches at hole-in-the-wall joints near Buckroe Beach, visited the Hampton University Museum’s Native American art collection, and haunted local antiques shops.

As a callow eighteen-year-old leaving for college, I’d seen my hometown as a mere launching pad for a life in worldlier locales, a place to be from rather than a place to be. But years and miles away from home could never attenuate the city’s hold on my identity, and the more I explored places and people far from Hampton, the more my status as one of its daughters came to mean to me.

That day after church, we spent a long while catching up with the formidable Mrs. Land, who had been one of my favorite Sunday school teachers. Kathaleen Land, a retired NASA mathematician, still lived on her own well into her nineties and never missed a Sunday at church. We said our good-byes to her and clambered into the minivan, off to a family brunch. “A lot of the women around here, black and white, worked as computers,” my father said, glancing at Aran in the rearview mirror but addressing us both. “Kathryn Peddrew, Ophelia Taylor, Sue Wilder,” he said, ticking off a few more names. “And Katherine Johnson, who calculated the launch windows for the first astronauts.”

The narrative triggered memories decades old, of spending a much-treasured day off from school at my father’s office at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Langley Research Center. I rode shotgun in our 1970s Pontiac, my brother, Ben, and sister Lauren in the back as our father drove the twenty minutes from our house, straight over the Virgil I. Grissom Bridge, down Mercury Boulevard, to the road that led to the NASA gate. Daddy flashed his badge, and we sailed through to a campus of perfectly straight parallel streets lined from one end to the other by unremarkable two-story redbrick buildings. Only the giant hypersonic wind tunnel complex—a one-hundred-foot ridged silver sphere presiding over four sixty-foot smooth silver globes—offered visual evidence of the remarkable work occurring on an otherwise ordinary-looking campus.

Building 1236, my father’s daily destination, contained a byzantine complex of government-gray cubicles, perfumed with the grown-up smells of coffee and stale cigarette smoke. His engineering colleagues with their rumpled style and distracted manner seemed like exotic birds in a sanctuary. They gave us kids stacks of discarded 11×14 continuous-form computer paper, printed on one side with cryptic arrays of numbers, the blank side a canvas for crayon masterpieces. Women occupied many of the cubicles; they answered phones and sat in front of typewriters, but they also made hieroglyphic marks on transparent slides and conferred with my father and other men in the office on the stacks of documents that littered their desks. That so many of them were African American, many of them my grandmother’s age, struck me as simply a part of the natural order of things: growing up in Hampton, the face of science was brown like mine.

My dad joined Langley in 1964 as a coop student and retired in 2004 an internationally respected climate scientist. Five of my father’s seven siblings made their bones as engineers or technologists, and some of his best buddies—David Woods, Elijah Kent, Weldon Staton—carved out successful engineering careers at Langley. Our next-door neighbor taught physics at Hampton University. Our church abounded with mathematicians. Supersonics experts held leadership positions in my mother’s sorority, and electrical engineers sat on the board of my parents’ college alumni associations. My aunt Julia’s husband, Charles Foxx, was the son of Ruth Bates Harris, a career civil servant and fierce advocate for the advancement of women and minorities; in 1974, NASA appointed her deputy assistant administrator, the highest-ranking woman at the agency. The community certainly included black English professors, like my mother, as well as black doctors and dentists, black mechanics, janitors, and contractors, black cobblers, wedding planners, real estate agents, and undertakers, several black lawyers, and a handful of black Mary Kay salespeople. As a child, however, I knew so many African Americans working in science, math, and engineering that I thought that’s just what black folks did.

My father, growing up during segregation, experienced a different reality. “Become a physical education teacher,” my grandfather said in 1962 to his eighteen-year-old son, who was hell-bent on studying electrical engineering at historically black Norfolk State College.

In those days, college-educated African Americans with book smarts and common sense put their chips on teaching jobs or sought work at the post office. But my father, who built his first rocket in junior high metal shop class following the Sputnik launch in 1957, defied my grandfather and plunged full steam ahead into engineering. Of course, my grandfather’s fears that it would be difficult for a black man to break into engineering weren’t unfounded. As late as 1970, just 1 percent of all American engineers were black—a number that doubled to a whopping 2 percent by 1984. Still, the federal government was the most reliable employer of African Americans in the sciences and technology: in 1984, 8.4 percent of NASA’s engineers were black.

NASA’s African American employees learned to navigate their way through the space agency’s engineering culture, and their successes in turn afforded their children previously unimaginable access to American society. Growing up with white friends and attending integrated schools, I took much of the groundwork they’d laid for granted.

Every day I watched my father put on a suit and back out of the driveway to make the twenty-minute drive to Building 1236, demanding the best from himself in order to give his best to the space program and to his family. Working at Langley, my father secured my family’s place in the comfortable middle class, and Langley became one of the anchors of our social life. Every summer, my siblings and I saved our allowances to buy tickets to ride ponies at the annual NASA carnival. Year after year, I confided my Christmas wish list to the NASA Santa at the Langley children’s Christmas party. For years, Ben, Lauren, and my youngest sister, Jocelyn, still a toddler, sat in the bleachers of the Langley Activities Building on Thursday nights, rooting for my dad and his “NBA” (NASA Basketball Association) team, the Stars. I was as much a product of NASA as the Moon landing.

The spark of curiosity soon became an all-consuming fire. I peppered my father with questions about his early days at Langley during the mid-1960s, questions I’d never asked before. The following Sunday I interviewed Mrs. Land about the early days of Langley’s computing pool, when part of her job responsibility was knowing which bathroom was marked for “colored” employees. And less than a week later I was sitting on the couch in Katherine Johnson’s living room, under a framed American flag that had been to the Moon, listening to a ninety-three-year-old with a memory sharper than mine recall segregated buses, years of teaching and raising a family, and working out the trajectory for John Glenn’s spaceflight. I listened to Christine Darden’s stories of long years spent as a data analyst, waiting for the chance to prove herself as an engineer.

Even as a professional in an integrated world, I had been the only black woman in enough drawing rooms and boardrooms to have an inkling of the chutzpah it took for an African American woman in a segregated southern workplace to tell her bosses she was sure her calculations would put a man on the Moon. These women’s paths set the stage for mine; immersing myself in their stories helped me understand my own.

Even if the tale had begun and ended with the first five black women who went to work at Langley’s segregated west side in May 1943—the women later known as the “West Computers”—I still would have committed myself to recording the facts and circumstances of their lives. Just as islands—isolated places with unique, rich biodiversity—have relevance for the ecosystems everywhere, so does studying seemingly isolated or overlooked people and events from the past turn up unexpected connections and insights to modern life. The idea that black women had been recruited to work as mathematicians at the NASA installation in the South during the days of segregation defies our expectations and challenges much of what we think we know about American history. It’s a great story, and that alone makes it worth telling.

In the early stages of researching this book, I shared details of what I had found with experts on the history of the space agency. To a person they encouraged what they viewed as a valuable addition to the body of knowledge, though some questioned the magnitude of the story.

“How many women are we talking about? Five or six?”

I had known more than that number just growing up in Hampton, but even I was surprised at how the numbers kept adding up. These women showed u...

Table of contents

- Contents

- Sample Chapters from Hidden Figures

- Teaching Guide for Margot Lee Shetterly’s Hidden Figures

- About This Guide’s Author

- Buy the Book

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Hidden Figures Teaching Guide by Margot Lee Shetterly,Kim Racon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Teaching Mathematics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.