![]()

Part One

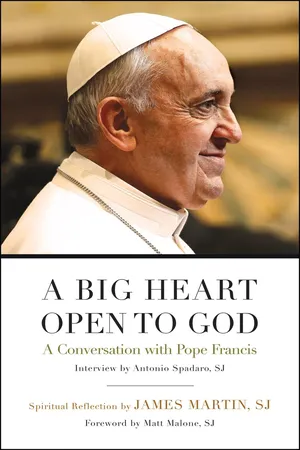

A Big Heart Open to God

The Exclusive Interview with Pope Francis

THIS INTERVIEW WITH Pope Francis took place over the course of three meetings during August 2013 in Rome. The interview was conducted in person by Antonio Spadaro, SJ, editor in chief of La Civiltà Cattolica, the Italian Jesuit journal. Father Spadaro conducted the interview on behalf of La Civiltà Cattolica, America, and several other major Jesuit journals around the world. The editorial teams at each of the journals prepared questions and sent them to Father Spadaro, who then organized and consolidated them. The interview was conducted in Italian. After the Italian text was officially approved, America commissioned a team of five independent experts to translate it into English: Massimo Faggioli, Sarah Christopher Faggioli, Dominic Robinson, SJ, Patrick J. Howell, SJ, and Griffin Oleynick. America is solely responsible for the accuracy of this translation.

![]()

Introduction

IT IS MONDAY, August 19, 2013. I have an appointment with Pope Francis at 10 a.m. in Santa Marta. I, however, inherited from my father the habit of arriving early for everything. The people who welcome me tell me to make myself comfortable in one of the parlors. I do not have to wait for long, and after a few minutes I am brought over to the lift. This short wait gave me the opportunity to remember the meeting in Lisbon of the editors of a number of journals of the Society of Jesus, at which the proposal emerged to publish jointly an interview with the pope. I had a discussion with the other editors, during which we proposed some questions that would express everyone’s interests. I emerge from the lift, and I see the pope already waiting for me at the door. In meeting him here, I had the pleasant impression that I was not crossing any threshold.

I enter his room, and the pope invites me to sit in his easy chair. He himself sits on a chair that is higher and stiffer because of his back problems. The setting is simple, austere. The workspace occupied by the desk is small. I am impressed not only by the simplicity of the furniture, but also by the objects in the room. There are only a few. These include an icon of St. Francis, a statue of Our Lady of Luján (patron saint of Argentina), a crucifix, and a statue of St. Joseph sleeping, very similar to the one which I had seen in his office at the Colegio Máximo de San Miguel, where he was rector and also provincial superior. The spirituality of Jorge Mario Bergoglio is not made of “harmonized energies,” as he would call them, but of human faces: Christ, St. Francis, St. Joseph, and Mary.

The pope welcomes me with that smile that has already traveled all around the world, that same smile that opens hearts. We begin speaking about many things, but above all about his trip to Brazil. The pope considers it a true grace.

I ask him if he has had time to rest. He tells me that yes, he is doing well, but above all that World Youth Day was for him a “mystery.” He says that he is not used to talking to so many people: “I manage to look at individual persons, one at a time, to enter into personal contact with whomever I have in front of me. I’m not used to the masses.”

I tell him that it is true, that people notice it, and that it makes a big impression on everyone. You can tell that whenever he is among a crowd of people his eyes actually rest on individual persons. Then the television cameras project the images, and everyone can see them. This way he can feel free to remain in direct contact, at least with his eyes, with the individuals he has in front of him. To me, he seems happy about this: that he can be who he is, that he does not have to alter his ordinary way of communicating with others, even when he is in front of millions of people, as happened on the beach at Copacabana.

Before I switch on the voice recorder we also talk about other things. Commenting on one of my own publications, he tells me that the two contemporary French thinkers that he holds dear are Henri de Lubac, SJ, and Michel de Certeau, SJ. I also speak to him about more personal matters. He too speaks to me on a personal level, in particular about his election to the pontificate. He tells me that when he began to realize that he might be elected, on Wednesday, March 13, during lunch, he felt a deep and inexplicable peace and interior consolation come over him along with a great darkness, a deep obscurity about everything else. And those feelings accompanied him until his election later that day.

Actually I would have liked to continue speaking with him in this very personal manner for much longer, but I take up my papers filled with questions that I had written down before, and I turn on the voice recorder. First of all I thank him on behalf of all the editors of the various Jesuit magazines that will publish this interview.

Just a bit before the audience that the pope granted on June 14 to the Jesuits of La Civiltà Cattolica, the pope had spoken to me about his great difficulty in giving interviews. He had told me that he prefers to think carefully rather than give quick responses to on-the-spot interviews. He feels that the right answers come to him after having already given his initial response. “I did not recognize myself when I responded to the journalists asking me questions on the return flight from Rio de Janeiro,” he tells me. But it is true: many times in this interview the pope interrupted what he was saying in response to a question several times in order to add something to an earlier response. Talking with Pope Francis is a kind of volcanic flow of ideas that are bound up with each other. Even taking notes gives me an uncomfortable feeling, as if I were trying to suppress a surging spring of dialogue. It is clear that Pope Francis is more used to having conversations than to giving lectures.

![]()

Who Is Jorge Mario Bergoglio?

I HAVE THE first question ready, but then I decide not to follow the script that I had prepared for myself, and I ask him point-blank: “Who is Jorge Mario Bergoglio?”

The pope stares at me in silence.

I ask him if this is a question that I am allowed to ask.

He nods that it is, and he tells me: “I do not know what might be the most fitting description. . . . I am a sinner. This is the most accurate definition. It is not a figure of speech, a literary genre. I am a sinner.”

The pope continues to reflect and concentrate, as if he did not expect this question, as if he were forced to reflect further.

“Yes, perhaps I can say that I am a bit astute, that I can adapt to circumstances, but it is also true that I am a bit naïve. Yes, but the best summary, the one that comes more from the inside and I feel most true is this: I am a sinner whom the Lord has looked upon.” And he repeats, “I am one who is looked upon by the Lord. I always felt my motto, Miserando atque eligendo [By Having Mercy and by Choosing Him], was very true for me.”

The motto is taken from the Homilies of Bede the Venerable, who writes in his comments on the Gospel story of the calling of Matthew: “Jesus saw a publican, and since he looked at him with feelings of love and chose him, he said to him, ‘Follow me.’ ” The pope adds, “I think the Latin gerund miserando is impossible to translate in both Italian and Spanish. I like to translate it with another gerund that does not exist: misericordiando [mercy-ing].”

Pope Francis continues his reflection and tells me, in a change of topic that I do not immediately understand, “I do not know Rome well. I know a few things. These include the Basilica of St. Mary Major; I always used to go there.”

I laugh and I tell him, “We all understood that very well, Holy Father!”

“Right, yes,” the pope continues. “I know St. Mary Major, St. Peter’s . . . but when I had to come to Rome, I always stayed in [the neighborhood of] Via della Scrofa. From there I often visited the Church of St. Louis of France, and I went there to contemplate the painting of The Calling of St. Matthew, by Caravaggio.”

I begin to intuit what the pope wants to tell me.

“That finger of Jesus, pointing at Matthew. That’s me. I feel like him. Like Matthew.” Here the pope becomes determined, as if he had finally found the image he was looking for. “It is the gesture of Matthew that strikes me: he holds on to his money as if to say, ‘No, not me! No, this money is mine.’ Here, this is me, a sinner on whom the Lord has turned his gaze. And this is what I said when they asked me if I would accept my election as pontiff.” Then the pope whispers in Latin, “I am a sinner, but I trust in the infinite mercy and patience of our Lord Jesus Christ, and I accept in a spirit of penance.”

![]()

Why Did You Become a Jesuit?

I UNDERSTAND THAT this motto of acceptance is for Pope Francis also a badge of identity. There was nothing left to add. I continue with the first question that I was going to ask: “Holy Father, what made you choose to enter the Society of Jesus? What struck you about the Jesuit order?”

“I wanted something more. But I did not know what. I entered the diocesan seminary. I liked the Dominicans, and I had Dominican friends. But then I chose the Society of Jesus, which I knew well because the seminary was entrusted to the Jesuits. Three things in particular struck me about the Society: the missionary spirit, community, and discipline. And this is strange, because I am a really, really undisciplined person. But their discipline, the way they manage their time—these things struck me so much.

“And then a thing that is really important for me: community. I was always looking for a community. I did not see myself as a priest on my own. I need a community. And you can tell this by the fact that I am here in Santa Marta. At the time of the conclave I lived in Room 207. (The rooms were assigned by drawing lots.) This room where we are now was a guest room. I chose to live here, in Room 201, because when I took possession of the papal apartment, inside myself I distinctly heard a ‘no.’ The papal apartment in the Apostolic Palace is not luxurious. It is old, tastefully decorated, and large, but not luxurious. But in the end it is like an inverted funnel. It is big and spacious, but the entrance is really tight. People can come only in dribs and drabs, and I cannot live without people. I need to live my life with others.”

While the pope speaks about mission and community, I recall all of those documents of the Society of Jesus that talk about a “community for mission,” and I find them among his words.

![]()

What Does It Mean for a Jesuit to Be Bishop of Rome?

I WANT TO continue along this line, and I ask the pope a question regarding the fact that he is the first Jesuit to be elected Bishop of Rome: “How do you understand the role of service to the universal church that you have been called to play in the light of Ignatian spirituality? What does it mean for a Jesuit to be elected pope? What element of Ignatian spirituality helps you live your ministry?”

“Discernment,” he replies. “Discernment is one of the things that worked inside St. Ignatius. For him it is an instrument of struggle in order to know the Lord and follow him more closely. I was always struck by a saying that describes the vision of Ignatius: Non coerceri a maximo, sed contineri a minimo divinum est [Not to be limited by the greatest and yet to be contained in the tiniest—this is the divine]. I thought a lot about this phrase in connection with the issue of different roles in the government of the church, about becoming the superior of somebody else: it is important not to be restricted by a larger space, and it is important to be able to stay in restricted spaces. This virtue of the large and small is magnanimity. Thanks to magnanimity, we can always look at the horizon from the position where we are. That means being able to do the little things of every day with a big heart open to God and to others. That means being able to appreciate the small things inside large horizons, those of the kingdom of God.

“This motto,” the pope continues, “offers parameters to assume a correct position for discernment, in order to hear the things of God from God’s ‘point of view.’ According to St. Ignatius, great principles must be embodied in the circumstances of place, time, and people. In his own way, John XXIII adopted this attitude with regard to the government of the church, when he repeated the motto, ‘See everything; turn a blind eye to much; correct a little.’ John XXIII saw all things, the maximum dimension, but he chose to correct a few, the minimum dimension. You can have large projects and implement them by means of a few of the smallest things. Or you can use weak means that are more effective than strong ones, as Paul also said in his First Letter to the Corinthians.

“This discernment takes time. For example, many think that changes and reforms can take place in a short time. I believe that we always need time to lay the foundations for real, effective change. And this is the time of discernment. Sometimes discernment instead urges us to do precisely what you had at first thought you would do later. And that is what has happened to me in recent months. Discernment is always done in the presence of the Lord, looking at the signs, listening to the things that happen, the feeling of the people, especially the poor. My choices, including those related to the day-to-day aspects of life, like the use of a modest car, are related to a spiritual discernment that responds to a need that arises from looking at things, at people, and from reading the signs of the times. Discernment in the Lord guides me in my way of governing.

“But I am always wary of decisions made hastily. I am always wary of the first decision, that is, the first thing that comes to my mind if I have to make a decision. This is usually the wrong thing. I have to wait and assess, looking deep into myself, taking the necessary time. The wisdom of discernment redeems the necessary ambiguity of life and helps us find the most appropriate means, which do not always coincide with what looks great and strong.”

![]()

The Society of Jesus

DISCERNMENT IS THEREFORE a pillar of the spirituality of Pope Francis. It expresses in a particular manner his Jesuit identity. I ask him then how the Society of Jesus can be of service to the church today, and what characteristics set it apart. I also ask him to comment on the possible risks that the Society runs.

“The Society of Jesus is an institution in tension,” the pope replied, “always fundamentally in tension. A Jesuit is a person who is not centered in himself. The Society itself also looks to a center outside itself; its center is Christ and his church. So if the Society centers itself in Christ and the church, it has two fundamental points of reference for its balance and for being able to live on the margins, on the frontier. If it looks too much in upon itself, it puts itself at the center as a very solid, very well ‘armed’ structure, but then it runs the risk of feeling safe and self-sufficient. The Society must alw...