ANY BOOK ABOUT VIRTUAL REALITY HAS TO START WITH A DEFINITION of what reality is in the first place. Given that philosophers have wrestled with this subject for millennia, it’s not a simple task. Take the question What is real? Merely by asking it, we suppose there must be some things we experience that are, in fact, not real. For some, this is an obvious point. My kitchen table—that’s real. The Greek god Zeus? Not so much. Real, not real…end of story.

Well, not so fast.

WHAT IS REALITY?

For humans, reality is, strictly speaking, constructed by minds. Many scientists, writers, and philosophers, such as Aldous Huxley, and even religious gurus like the Dalai Lama, have argued that all perceptions are actually just hallucinations, and idiosyncratic ones at that. Scientists know that what people see, hear, touch, smell, and taste are really impoverished versions of external stimuli. We know, for example, that there are more colors in the light spectrum than can be seen by humans, such as infrared, and more odors than can be smelled, such as carbon monoxide. Furthermore, the qualities of sensory stimuli that people perceive, such as the color of the sky, the smell of a rose, the feel of sandpaper, the sound of a low C on a piano, are not necessarily the same for everybody.

That people differ in their perceptions of sensory stimuli is indisputable. Nearsighted individuals see faraway objects less clearly than farsighted ones, and vice versa. Anosmic people can’t smell. Others can’t hear things particularly well. Some perceptual differences are genetic (e.g., people born with a gene that makes Brussels sprouts taste bad), some are maturational (e.g., infants and older people generally have poorer vision than children, adolescents, and young adults), and some result from disease or injury (e.g., a colleague of ours lost his sense of smell after falling and cracking his skull). Forget walking a mile in someone else’s shoes, just move an inch using her senses and you would perceive reality differently.

Taking all of this into account, one might concede that reality is subjective but conclude that it’s still a constant for each of us individually. But, even within a single mind, reality is in constant flux. Consider red-green color-blindness, the inability to differentiate those two colors. Statistically, 8 percent of men and less than 1 percent of women are afflicted. However, everyone experiences a form of color-blindness every day. Look at the corner of a room in which the intersecting walls were painted the same color. In answer to the question What color are the two walls? most people would name a single color, such as “sandalwood” or “buckskin” or whatever color the walls were painted. The assumption that the walls are painted the same hue drives people’s mental perception, hence the answer. However, light in the room very likely reflects off the walls differently on the way back to one’s retina. Consequently, the wavelength of the light—which defines the color—coming from each wall is different. Yet, most people fail to perceive the color difference and are temporarily color-blind. The perceptual system makes the walls seem the same color, simplifying the world for the viewer, even though viewers can override this perceptual process when they consciously try to notice the different colors on each wall. Perceptionists label this phenomenon “color constancy.”

Nothing is particularly unsettling about the subjective manner in which people perceive reality. Sure, we see things differently from one another, and even from ourselves from time to time, but we still manage to come to a general agreement of what’s collectively in front of us and to share our perceptions with each other. Those deviating from this collective perception, people who see, hear, or feel things that aren’t physically there at all, are usually labeled crazy, victims of faulty wiring, etc. “Son of Sam” serial killer David Berkowitz, who heard voices, and Nobel laureate John Nash, who had recurring hallucinations of nonexistent people, are famous examples. It turns out, however, that even the reality shared by the “normal” among us is not necessarily the same.

Many think of the famous journalist Carl Bernstein as a man who can uncover information better than most Americans. After all, he and Bob Woodward were responsible for bringing the Watergate scandal to light. His ex-wife, however, disagreed. In her semiautobiographical novel, Heartburn, Nora Ephron wrote about her marriage, presumably with Bernstein, and humorously described the blinding effect of refrigerator light on the male cornea. This occurs when males open the refrigerator door to look for the butter and invariably ask (to no one in particular), “Where’s the butter?” Sooner or later, and with exasperation, their spouses come to look at the open refrigerator and immediately point out that “It’s right there!”—unblocked and in plain view. Ephron concluded, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, that despite the butter being displayed prominently in the male visual field, the male brain cannot pick it out of the array of other visual objects.

On a more scientific note, the University of Illinois perception scholar Dan Simons has studied similar behavior, albeit common to both sexes, labeling it “inattentional blindness,” drawing particularly surprising results from a series of startling experiments. His book, The Invisible Gorilla, takes its name from these studies.

If we were to ask you to watch a video of two teams tossing a basketball among team members, and to count the number of times each team’s players passed the ball, do you think you would notice if a gorilla walked on to the court among the players? Of course, you say? Surprisingly though, chances are about one in two that you would not.

In Simons’s now classic experiment, people watched videos of teams passing basketballs and counted the number of passes. As the action in the video unfolds, a gorilla (okay, a person in a gorilla suit) actually walks into the middle of the players, stops, beats its chest, and walks off the scene—taking from five to ten seconds to do so. A minute later, the video stops. Across several experiments, roughly half (46 percent) of the viewers did not report seeing the gorilla! We’ve tried this same experiment in our classes at Stanford and the University of California, Santa Barbara, and literally half the class shrieks in surprise when we show them the video the second time and instruct them to look for the gorilla. This inattentional blindness, or “not seeing things that are there,” is also one of the keys to sleight-of-hand magic acts. (Try it yourself at www.invisiblegorilla.com.)

The invisible gorilla in action.

Courtesy of Daniel Simons

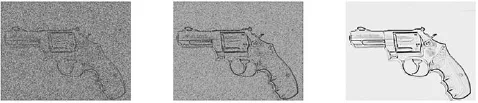

While spotting gorillas may no longer be a critical skill to people outside of the jungle, subjectivities in perception can have serious consequences. For example, people with racial bias actually see the world differently. Stanford’s Jennifer Eberhardt, who studies racial prejudice and discrimination, has conducted a series of experiments that supports this notion. In the context of an experiment purportedly about how the human visual system works, Eberhardt told research participants to stare at a dot in the center of a computer screen, during which time she flashed photographs subliminally of black or white faces. The participants could see a brief color flash on the screen, but they weren’t consciously aware that there were pictures of people popping up in front of them, and none reported ever seeing them.

Subsequently, Eberhardt presented the research participants a series of images consisting of a few dots, and then a few more, and a few more, and a few more, etc., until they could identify the object she was trying to depict. She was studying how many dots it would take before they could recognize the emerging object. Some of the pictures were of everyday household objects, such as hand tools. When household objects were the pictures in question, the prior subliminal flashes of either black or white faces had no effect on the number of dots it took before participants could recognize the object being depicted. However, the flashes made a big difference for the recognition of one particular object—a handgun. The participants who had been exposed subliminally to the black faces perceived the handgun reliably sooner—that is, with less available sensory information (i.e., dots)—than those who had been exposed to the white faces. Eberhardt’s explanation is that the subliminal flashes of black faces had unconsciously activated violent racial stereotypes that “primed” her participants to see artifacts like a handgun, which are consistent with the stereotype. Outside of the laboratory, perhaps the priming effects that Professor Eberhardt discovered lead police to find more weapons when searching cars driven by blacks than those driven by whites, thereby reinforcing the idea of racial profiling.

Masked stimuli panels.

Courtesy of Crystal Nwaneri

Whether it’s a color that we see in a particular light, a gorilla we somehow miss, or a pattern we’re primed to detect, the evident variability of our perceptions undermines the common-sense notion of a hard-and-fast, fixed and static, easily defined reality. Ours is not a passive relationship, where reality is and we simply experience it; reality is, in fact, a product of our minds—an ever-changing program consisting of a constant stream of perceptions. And what we intend to show in the chapters ahead is how, in many ways, virtual reality is just an exercise in manipulating these perceptions.

THE PRINCIPLE OF “PSYCHOLOGICAL RELATIVITY”

Even though reality is an elusive target, most people easily divide the world between the real and the not-real. The takeaway message here is that the mind decides if perceptions are real. If the mind buys into an experience, it deems it “real,” otherwise it judges it to be unreal. And, if enough people share the perception that an alternative reality is real, then who’s to say it isn’t? The difference between heaven, which the great majority of Americans believe is real, and leprechauns, which are fiction to most, is determined largely by consensus, as opposed to scientific proof.

To bridge the gap between what is experienced as real and what is not, let’s take a cue from Einstein’s work on relativity. We’ve parsed human perceptions into two categories, “real” and “virtual,” via a concept called psychological relativity. Einstein introduced the modern notion of “special relativity,” theorizing that the perceived speed of objects depends on the observer’s own motion. In other words, what common sense tells people about movements is not always true. A speeding car appears to be moving faster if it passes you while you are stationary, than if you are driving on the highway with it. Or consider that people ordinarily believe they aren’t moving when they stand still, but astrophysicists know that they are moving—very fast, in fact. All people move with the rotation of the earth on its axis, Earth’s orbit around the sun, the solar system’s orbit around the Milky Way galaxy, the galaxy’s movement through the universe, and, finally, with the ever-expanding universe itself. Even on a microscopic level, subatomic particles are moving within every atom of the human body.

Analogously, the distinction between real and virtual is relative. Humans contrast what is usually considered “grounded reality”—what they believe to be the “natural” or “physical” world—with all other “virtual realities” they experience, such as dreams, literature, cartoons, movies, and online environments such as Facebook or Second Life. This contrast allows us to avoid being mired in the unending debate over what constitutes reality.

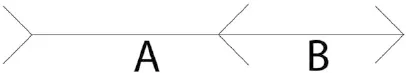

As we’ve already seen, people often experience and believe the illusory to be real. In the drawing below, for example, line A seems longer than line B, even though both are equal objectively. It takes only a moment’s reflection to realize that the distinction between “grounded” and “virtual” is often arbitrary—humans move between them.

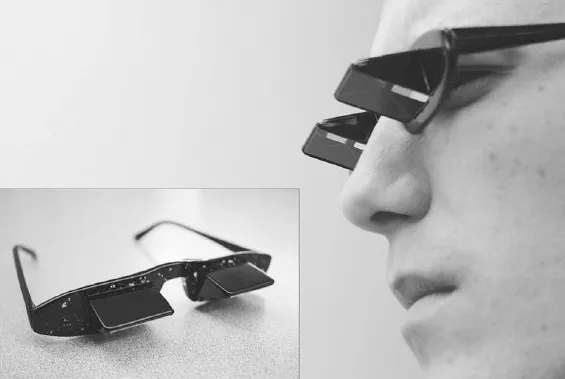

A century ago, a classic experiment illustrated how easily our minds transport us into virtual reality. In 1896, George M. Stratton, a professor at Berkeley, described his experiences using “prism glasses.” Professor Stratton wore eyeglasses with prism lenses that were designed to optically invert the physical environment, turning everything he viewed upside down. Stratton reported that he wore prism glasses from three P.M. until ten P.M. on the first day, then took them off in the dark and blindfolded himself before going to bed. Upon awakening about nine thirty the next morning in the dark room, he took off the blindfold and put the prism glasses back on, and wore them again until ten P.M. Similarly, the third day, he wore the prism glasses beginning at ten A.M. for two more hours before ending the experiment. Amazingly, on the first day, his perceptual system adjusted by re-inverting his view—even though the glasses were sending him images upside down, his brain interpreted the signal as right-side up.

The Müller-Lyer illusion.

Courtesy of Crystal Nwaneri

Many studies have since replicated Stratton’s introspective report. Indeed, such experiments have become common enough that one can find prism glasses available for purchase on the Web. At first, research participants generally see the physical world as if they are standing on their heads. However, in an unexpectedly short time, their perceptual system adjusts and they see the world as they would without the lenses. When they take off the prism glasses, the grounded world, which, by definition, is right-side up, actually appears upside-down for a while. Don’t worry though, eventually the participants adapted back to life without the prism glasses and saw the grounded world right-side up again.

The point here is that humans are neurophysiologically wired to subjectively “right” sensory stimuli according to previously established expectations. We hope you’re beginning to appreciate why people engage so readily in virtual worlds.

A tool to turn the world upside down.

Courtesy of Cody Karutz

STUMBLING INTO VIRTUAL REALITY

“Virtual reality” typically conjures up futuristic images of digital computer grids and intricate hardware. But we believe that virtual reality begins in the mind and requires no equipment whatsoever. Have you ever spoken face-to-face with someone whose mind wandered off? Have you been startled out of your own mental reverie by someone else waving her hand in front of your face and asking, “Where are you?” Indeed, everyone experiences being “somewhere else” in their own minds, whether they are conversing with others or not—at times for a few seconds, other times for much longer—as our minds wander amid imagined, remembered, or misremembered places. Anyone who’s sat through a boring meeting knows this.

Hungry people imagine what they’ll eat. Overweight people imagine being skinny. Single people crave the warmth and comfort of a soul mate. Married people yearn for the freedoms of single life. People who’ve acted stupidly will imagine what could have been if only they hadn’t. People who have lived their lives cautiously wish they would have been more daring once in a while.

The human mind is fundamentally designed to wander. So much so that it’s actually more difficult to think of nothing, to keep one’s mind totally “blank,” than to fill it with thoughts and fantasies. Unless you’re an expe...