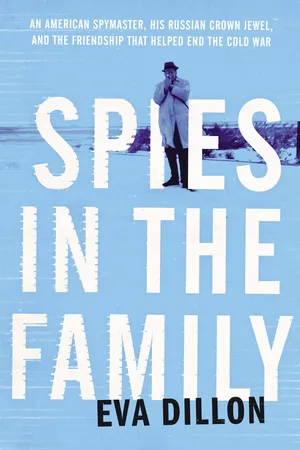

Captain Dmitri Fedorovich Polyakov, artillery officer, near the end of World War II. (Courtesy of Alexander Polyakov)

In the spring of 1951, a Soviet battle cruiser, the Molotov, slid into a berth on the Hudson River on New York’s Upper West Side. Once she was fully docked, a small group of Russian military and diplomatic officials disembarked, among them Lt. Col. Dmitri Fedorovich Polyakov; his wife, Nina; and their three-year-old son, Igor.

They were among the privileged. With the Iron Curtain firmly in place since the end of World War II, only certain Soviet citizens were allowed to travel, and they tended to be the best and the brightest. Some, usually the athletes and artists, were carefully watched so they wouldn’t defect. Others, the diplomats and official representatives, were more trusted. The Polyakovs were among the latter.

In his first foreign posting with the Soviet military, thirty-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Polyakov was a newly appointed member of the Soviet Mission to the United Nations Security Council Military Staff Committee. At least, that was his official role. His real job was as a spy.

Polyakov was a military intelligence officer in the Soviets’ largest foreign intelligence agency, the GRU. The Glavnoye Razvedyvatel’noye Upravleniye, or Main Intelligence Directorate, complemented and sometimes rivaled the better-known KGB.

While the KGB and GRU both employed spies, each had its own distinct mission. The KGB’s primary task was internal security, that is, spying on and suppressing domestic dissidents and closely watching foreigners who might express anti-Soviet sentiments or commit anti-Soviet activities: journalists, tourists, but most of all the diplomats and intelligence personnel of the capitalist enemies. The GRU, conversely, focused on external threats and stealing military technology. Like the CIA, it deployed its agents overseas in an ongoing endeavor to gather external intelligence. As a result, its force of spies working foreign targets was far larger than that of the KGB.

In the 1950s, with the wartime alliance between Russia and the West abandoned, the tension and mistrust that ruled the relationship between the Soviets and Americans pervaded their societies as well. Soviet propaganda portrayed America as a cesspool of drugs, crime, and sinister capitalist exploitation. In America, McCarthyism was at its height and the term Communist was fast becoming a slur. By the early 1950s, the GRU was focused like a laser on what was then being called the “Main Enemy,” the United States of America. Dmitri, Nina, and little Igor Polyakov had landed in this alien world, one that was both alluring, with its bustle, its skyscrapers, and its abundance of consumer goods, and ominous as the nucleus of international aggression and anti-Soviet subversion and hatred.

The Polyakovs were assigned a small apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, in a building occupied mainly by Soviet families from the United Nations. Exploring their new neighborhood, they were fascinated by the food stores, shops, and restaurants, the bright lights and electric energy of the city, such a contrast to the dismal gray of Stalinist Moscow.

Polyakov’s English was good but not fluent. Although he’d been preparing for this assignment for years, he spent his first months in America working with a special tutor to sharpen his language skills and become more familiar with the customs and habits of American life—what clothes to buy and how to wear them, questions of etiquette, even how to make small talk. He would need those skills for his work at the United Nations, attending General Assembly meetings, advising Russian diplomats on military affairs, and interacting with his counterparts in other countries’ delegations. But he needed them even more for his real job: stealing secret information.

Lieutenant Colonel Polyakov’s undercover GRU assignment was to run a network of “illegals,” spies the Soviets had slipped into the country with forged or stolen passports and identification. Posing as U.S. citizens, they came with fabricated backgrounds, life stories, or “legends,” about who they were, where they’d grown up, where they’d gone to school, and where they’d worked, all of it memorized. They kept low profiles and acted like ordinary citizens, integrating themselves into the fabric of American life.

Illegals had instructions to get access, especially, to technology industries, universities, and laboratories. Through the information they stole, Russia made quick progress copying America’s advanced technology. The designs of Soviet bombers, submarines, missiles, and weapons systems were accelerated and improved by access to stolen American technical designs, saving tens of billions of rubles in research and development.

Dmitri Polyakov’s diplomatic cover didn’t fool the FBI, which had identified him as a probable intelligence officer from the moment he arrived. The Bureau knew that the Soviet delegation’s military attaché position would likely be filled by a GRU officer, and therefore a spy. For the FBI’s Counterintelligence Division, Dmitri Polyakov was a person of considerable interest from day one.

Polyakov worked out of the stately redbrick Soviet Mission at 680 Park Avenue, across the street from Hunter College. One of the floors within the mission contained the clandestine offices of the GRU rezidentura, its base in New York. (Polyakov was the GRU’s deputy rezident, or deputy chief.)

Among the second-floor classrooms and offices of the Hunter College building across the street was a sealed room with an unobstructed view of the entrances to the Soviet Mission. The FBI rented the room from the college, no questions asked. From there, the agents could look down on and photograph everyone who came and went through the mission’s doors, including Polyakov, whose arrival each morning was recorded by his FBI watchers. Whenever he left the building, a radio call went out from the sealed room to watchers on the street, and tails fell into place behind Polyakov. In fact, hundreds of FBI agents in surveillance and investigative teams worked the Soviet target, which included others from the United Nations Mission as well as Polyakov.

One of those watchers was Ed Moody, a young FBI special agent who had been assigned to cover Polyakov. This was Moody’s first major assignment, and he was determined to make his mark by catching Polyakov in the act of espionage. Accordingly, Moody followed Polyakov everywhere, noting where he went and when, learning his habits and timing, keeping track of any contacts he made, all the while trying to distinguish innocent encounters and activities from suspicious ones.

Special Agent Moody was also trolling for vulnerabilities. FBI counterintelligence looked for Russians who might be susceptible to recruitment. Getting a Soviet intelligence officer to give up or sell precious secrets didn’t happen often, but when it did, it was considered a major coup.

Counterintelligence agents were keenly attuned to behavior that might signal that a Russian could be turned. At home, Russians were used to standing in line to buy standard consumer items or scarce food commodities, whereas in New York, market shelves were full and liquor and luxury goods were widely available. Had a Russian been buying things (gold earrings for a wife or girlfriend, a stereo system for himself) that were beyond his means? If he had, where was the money coming from? Was he gambling, stealing from office accounts, or in debt? Was the Russian an alcoholic, visiting prostitutes, cheating on his wife, or a homosexual? Could he be blackmailed? And to keep his superiors from learning of these susceptibilities (a situation that would surely result in an immediate return to Moscow and likely the loss of his job or worse), would he become an agent for the Americans? Approaching someone who might be responsive was, in FBI terms, a “courtship.” Could Dmitri Polyakov be courted?

Special Agent Moody scrutinized Polyakov’s movements, looking for signs of tradecraft: a quick brush pass handoff in a crowd, a surreptitious exchange of a small item at a coffee shop counter, picking up an envelope from one of his illegals at a dead drop (a hiding place where messages or intelligence could be left or collected). But Moody saw nothing. As a well-trained intelligence officer, Polyakov knew when he was being tailed, and was skilled at hiding his tradecraft. Moody noted another thing: Polyakov was particularly good at “going black,” that is, giving the FBI the slip. Also, to all appearances, he was a devoted family man who didn’t smoke and rarely drank. All this Moody noted in his file on Polyakov.

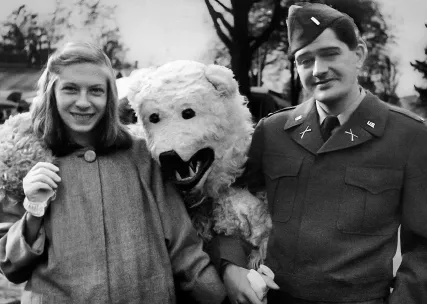

The Polyakovs, c. 1957. Left to right: Alexander, Dmitri, Petr, and Nina. (Courtesy of Sandy Grimes)

Three months after the Polyakovs arrived in New York, tragedy struck the family. With their husbands at work, Nina and the other Russian women in the residential building would go to Central Park where the children could run around and cool off in the summer heat, wading in the little corners of the lakes and ponds. One day in August, three-year-old Igor began to throw up. He also had a fever, and complained that his neck hurt. It was polio. In the late 1940s and early ’50s parents lived in fear of the summer polio season. One way the virus was thought to be contracted was through stagnant water in ponds or lakes. Two major outbreaks took place in 1951 and 1952, when more than fifty thousand cases were reported in the United States, resulting in thousands of fatalities. The polio vaccine was still five years away.

Igor’s symptoms were grave, and over time they worsened. His muscles weakened, and his cognitive ability seemed to be affected. Nina and Dmitri had all the medical assistance they needed, but there was little anyone could do other than to make him as comfortable as possible. (Years later it was widely reported, in both the American and Russian press, that Igor died shortly thereafter in New York City. But, in fact, he lived to the age of seventeen.)

Despite this period of personal misery, Polyakov’s career as a spy handler was going well. His illegals were producing, and he was regularly channeling useful reports back to Moscow Center. In 1953 he was promoted to full colonel.

Also that year, the Polyakovs celebrated the birth of a second son, Alexander, named after Dmitri’s mother, Alexandra. Another baby boy was born two years later, named after Nina’s father, Petr Kiselev, a colonel who had been Polyakov’s commander during the war. Colonel Kiselev and Polyakov had fought side by side in the frozen forests of Finnish Karelia, and again during the war’s last major German offensive, the Nazis’ Operation Spring Awakening, on the shores of Hungary’s Lake Balaton. The two men had created a bond then that only the desperation of war can forge.

Polyakov and Petr Kiselev came home from the war as heroes—the colonel with the Order of Lenin, the Soviet Union’s highest medal for valor, and Polyakov with the Order of the Patriotic War and Order of the Red Star for gallantry in action. Dmitri Polyakov had not only proven his courage, but demonstrated an ability to think creatively under pressure and to lead men in battle. As a result, he was offered a place in the Frunze Military Academy, Moscow’s prestigious general staff college. One of his class’s top graduates, he was then recruited into the GRU for advanced training as an intelligence operative, which readied him for clandestine warfare against his country’s new enemy: the United States of America.

By 1956 the Polyakovs had been living in the United States for five years. Their youngest sons, Alexander and Petr, had never been to Russia, and Dmitri and Nina had become acclimated to American life. Nina had studied English at Moscow State University; Polyakov’s language skills were improving, and he had deepened his knowledge of American history and political culture. But as Polyakov’s tour in the United States was coming to an end and the family prepared to return to Moscow, the seeds had likely been planted for what was to be the most momentous decision of his life.

FBI special agent Ed Moody registered Polyakov’s return to the USSR in July 1956. Without having collected any incriminating evidence on him, Moody closed his file and put it away.