- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

Imagination

Engage and Envision

Chapter 1

Engage

The Keys to the Building

Imagine staring at one painting for three hours. That’s what Jennifer Roberts, professor of History of Art and Architecture at Harvard, asks her students to do. This is part of a larger assignment in which the students intensively study one work of art. Before diving into secondary research in books or journals, they need to spend a painfully long time just observing the piece. At first, the students rebel, complaining that there can’t possibly be that much to see in a single object. When they’re done, however, they admit that they were “astonished by the potential this process unlocked.”

Jennifer Roberts shares her own experience with a 1765 painting by John Singleton Copley, called A Boy with a Flying Squirrel, in this excerpt from an article about her observations:

It took me nine minutes to notice that the shape of the boy’s ear precisely echoes that of the ruff along the squirrel’s belly—and that Copley was making some kind of connection between the animal and the human body and the sensory capacities of each. It was 21 minutes before I registered the fact that the fingers holding the chain exactly span the diameter of the water glass beneath them. It took a good 45 minutes before I realized that the seemingly random folds and wrinkles in the background curtain are actually perfect copies of the shapes of the boy’s ear and eye, as if Copley had imagined those sensory organs distributing or imprinting themselves on the surface behind him.

This exercise demonstrates that looking at something briefly doesn’t necessarily mean really seeing it. This is the case with all our senses. We so often listen but don’t really hear, touch without really feeling, look without really seeing.

To illustrate this point, I assigned a similar project to students in one of my courses. They were asked to take a silent walk for an hour, and to capture all that they heard and saw. Some chose a city setting, others the woods, and some sat at their own kitchen table. They made long lists of observations, realizing in the process that on most days they move so quickly—and noisily—through their lives that they miss the chance to observe what’s happening around them. This type of observation is not just a nice-to-have addition to our lives, but is the key to a door of opportunities. By actively engaging in the world, you begin noticing patterns and opportunities.

Consider the story of the founding of Lyft, which along with other ride-sharing firms is changing the way people get around town. It all started in Zimbabwe, Africa, where Logan Green was traveling for pleasure. He noticed that drivers traveling on the crowded streets picked up people along the way. A small car might be packed with ten people, all happy to hitch a ride. Logan contrasted this with his experience back at home in the United States, where most cars have a single passenger and the roads are clogged with commuters. He was inspired to consider a similar concept at home. This was the birth of Zimride, named for Zimbabwe.

Over time the strategy for Zimride evolved from arranging carpools for universities and companies to a mobile ride-sharing platform. The company changed its name to Lyft, but the initial vision for the firm remained, triggered by Logan’s observation of ride sharing along a bustling road in Africa.

I often meet individuals who are desperately looking deep inside themselves to find something that will drive their passion. They miss the fact that, for most of us, our actions lead to our passion, not the other way around. Passions are not innate, but grow from our experiences. For example, if you never heard a violin, kicked a ball, or cracked an egg, you’d never know that you enjoy classical music, soccer, or cooking, respectively.

Consider Scott Harrison’s story, told in the opening to part 1. He applied to volunteer at dozens of organizations and joined the one group that accepted him. It could have been any organization. In fact, it didn’t matter which one. Once he was involved, he started experiencing things he’d never seen before, and started asking questions—lots of questions. He wanted to know why there were so many sick people in Liberia, why they had illnesses he had never seen before, and what was causing those diseases. The answers to these questions moved him to ask even more questions about how to address the problem of waterborne illnesses. Before he got involved, he didn’t have a passion to deliver clean water to millions of people. His passion grew from engagement.

Your first step toward developing a passion need not be glamorous. If you took a job as a waiter in a restaurant, for instance, you would have the chance to interact with hundreds of people each day and to see the world from a unique perspective. There are countless lessons you would learn from this experience, along with opportunities for inspiration. For example, you might discover secrets to effective customer service and then dive into learning how to help others improve their hospitality skills. You might become fascinated with the dietary requirements of some of your customers and then decide to open a restaurant that addresses their needs. Or you might talk with a customer and discover that she has diabetes and, after learning about her challenges, take on that cause.

Just as there are almost infinite passions you could develop, so too are there wide-ranging directions you could take your new passion once it grips you. If you decide to focus on customer service, for example, you might develop a guide for best practices in the hospitality industry, launch a consulting business, make a documentary, or start a new restaurant. Without your initial experience as a waiter in a restaurant, you would never have found this new calling. In each case, once you open the door to a particular destination, you reveal a set of paths that you probably didn’t know existed. In fact, before it’s your cause, it’s likely something about which you knew nothing.

Love at first sight is rare in most aspects of life. The more experience you have with a person, a profession, or a problem, the more passionate and engaged you become. Let’s take this comparison further: If you want to get married, the last thing you should do is sit alone, waiting for the phone to ring, or for Prince or Princess Charming to show up at your door. The best chance to find a compatible match is to meet lots of people. Your attitude (affection) follows your actions (dating), not the other way around. Yes, the dating process can be filled with false starts and disappointments, but you will never be successful unless you embrace the process of discovery.

Discovery is predicated on curiosity. The more curious you are, the more willing you will be to engage in each new experience. The easiest way to tap into your natural curiosity is by asking questions. Instead of accepting everything you see, or bypassing things that don’t make sense to you, question everything. Using the earlier example of being a waiter, each day you might question why that day you receive more (or fewer) tips than the day before; why the restaurant is filled with customers of a particular demographic; or why some items on the menu are never ordered. Answering these questions leads to more questions, opens the door to interesting insights, and exercises your curiosity muscles.

Chip Conley, author of Emotional Equations, describes curiosity as fertilizer for the mind. He says, “There’s lots of evidence to suggest that it’s like blood in our veins, an essential, life-affirming emotion that keeps us forever young.” We all know that children are naturally curious, asking endless questions, such as why the sky is blue, why water is wet, and why they have to go to bed so early. Unfortunately, that curiosity is often quashed by responses such as, “Because I said so.” Instead of answering flippantly, we would do well to use these questions as a springboard, encouraging children to find out the answers for themselves. (We can do this as adults, too, by looking up answers or performing experiments.) For example, the child who doesn’t know why he or she should go to sleep so early could run an experiment to see how the body feels after getting differing amounts of sleep. Learning to answer your own questions—whether you are young or old—fuels curiosity, imagination, and confidence.

Scott Barry Kaufman, the scientific director of the Imagination Institute at the University of Pennsylvania, focuses on the measurement and development of intelligence and creativity. In a recent article, titled “From Evaluation to Inspiration,” he discusses the importance of training yourself to be curious and inspired by the world. He writes:

Inspiration awakens us to new possibilities by allowing us to transcend our ordinary experiences and limitations. Inspiration propels a person from apathy to possibility, and transforms the way we perceive our own capabilities. Inspiration may sometimes be overlooked because of its elusive nature. . . . But as recent research shows, inspiration can be activated, captured, and manipulated, and it has a major effect on important life outcomes.

Scott goes on to outline the things we can do to boost our ability to be inspired, including being open to new experiences, having a positive attitude, surrounding ourselves with inspiring role models, and recognizing the power of inspiration in our lives. Essentially, curiosity and inspiration are mind-sets that we can control. By fueling those mind-sets, we unlock countless opportunities.

My colleagues, Bill Burnett and Dave Evans teach a course at Stanford called “Designing Your Life.” In it they help young people unlock their curiosity and imagination, while providing tools for exploring and evaluating the possibilities in front of them. Bill and Dave provide students with a set of tools for reframing and prototyping alternative visions for their career, and bring in a wide range of people to share their professional journeys. This exposes the students to an incredible array of possible paths. Their final project involves crafting three completely different versions of their next five years. The students learn that it is up to them to invent their own future, and that they have the power to choose which vision to make real. They also learn that one’s path is rarely straight, and there is a complex dance between vision and revision, based on our unfolding experiences.

Engage ↔ Envision

There have been many times in my life that I, like Scott Harrison, have looked for a new direction. In each case, I applied to seemingly endless organizations, and with each application I imagined what it would be like to work there, knowing that each opportunity would open up a brand-new world of opportunities. Would I end up in a laboratory, a corporate office, a classroom, or on an expedition boat? Any and all of these were possible.

Eighteen years ago, I stumbled upon the job description for the assistant director role at the Stanford Technology Ventures Program (STVP), the then-new entrepreneurship center at the Stanford School of Engineering. It sounded intriguing, but I crumpled up the job description and threw it in the trash. You see, I had much more experience than was required for the position, and the salary was really low.

The next day, I pulled the piece of paper out of the trash and flattened it. Why not apply? It couldn’t hurt, right? As it turns out, the more I learned through the interview process, the more fascinated I became with the opportunity, and I was fortunate enough to be offered the job. Despite the lower level of the role, I would get a chance to work with an amazing group of people on an exciting new initiative.

Once in the door, I soaked up everything I could about entrepreneurship and innovation. I volunteered for more and more projects, building my knowledge and experience. The more I learned, the more opportunities unfolded. Over the years, together with my colleagues, we launched new courses, developed international partnerships, and built an online platform to share our content. Based on the success of these initiatives, we raised funds to grow our team, allowing STVP to continue to grow. I wrote books based on what I’d learned, and was rewarded in many ways, including the chance to travel around the world, sharing what we had done and helping others build their entrepreneurship programs.

None of these roles were in the initial job description; they developed over the years, with more and more engagement. And nobody gave me that road map—I had to create it myself. In fact, when you get a job—any job—you aren’t given just that job, but rather the keys to the building. It’s up to you to decide where they will take you.

I’ve often wondered what would have happened if I had been given the keys to a different building. What I do know is that each one would have held a world of possibilities waiting to be discovered. As I walk across the Stanford campus now, I often think of all the other disciplines that would have sparked my imagination, from education reform to climate change. Had I walked through a different door, an entirely different, and equally stimulating, path would have emerged.

Over the years I’ve learned that everything is interesting once you approach it with an attitude of curiosity. Right after graduate school, I spent two years in a management consulting firm. As a junior associate, I was put on any project that needed a warm body, irrespective of my interest or expertise. At different times, I was on a team focused on nuclear power plant construction, on telecommunications infrastructure, and on compensation plans for hospital management. In each case, I walked in cold and learned about the field. Within a few weeks, it was clear that each one of these areas was fascinating, steeped in historical and social context, complicated by technical requirements, and full of opportun...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Letter to Readers

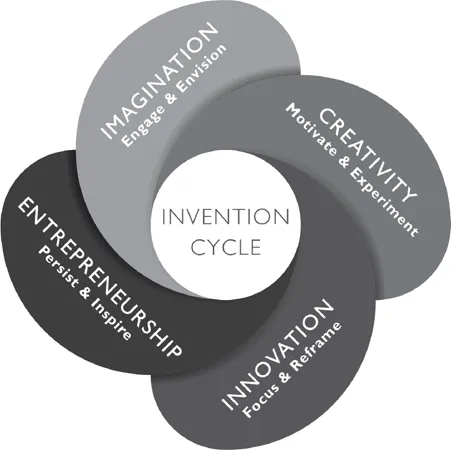

- Introduction: Inspiration to Implementation

- Part One: Imagination

- Part Two: Creativity

- Part Three: Innovation

- Part Four: Entrepreneurship

- Conclusion: The End Is the Beginning

- Acknowledgments

- Summary of Projects

- Insights

- References

- Index

- About the Author

- Also by Tina Seelig

- Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Creativity Rules by Tina Seelig in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Commerce & Prise de décision. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.